B.G. man volunteered to fight in later wars

BATTLE GROUND — After spending World War II in the U.S. Navy, George Bennett was ready to serve his country again during the Korean War.

A decade later, he was set to report for duty during the 1962 Cuban missile crisis. During the Vietnam War in the 1970s, Bennett volunteered to return to active duty. Twice.

Bennett traces part of his four-decade call to duty to a memorable supper 68 years ago in Hawaii. It was the evening of Dec. 7. The people sharing the hasty meal had just survived the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Not everybody was as lucky.

“When we got to the mess hall, half of it was dark,” Bennett said. In that darkened section, “rolled in blankets, were the burned bodies of men who had died on battleships,” he said.

“Try to eat with that smell.”

It really brought home the impact of war, Bennett said. “That’s part of the reason I stayed in the Navy Reserve.”

After six years on active duty and 37 years in the Reserve, he retired in 1984 at the age of 60.

He was not recalled to active duty during that span, but it wasn’t for lack of trying.

“I almost was activated when the Cuban crisis got hot,” Bennett said. “They notified me to leave, I was ready, and it was cancelled.”

During the Korean War, he ran into paperwork issues.

When he checked in at a Navy Reserve center, “The guy’s desk was covered with records. He said, ‘Don’t call me; I’ll call you.’

“During Vietnam, I volunteered twice. They said they had so many Navy volunteers that there was no position open.”

The Battle Ground resident is back in uniform today at Pearl Harbor. He’s a guest at the ceremony honoring those who lost their lives on Dec. 7, 1941.

Bennett has returned to Hawaii several times for Dec. 7 commemorative events, as well as anniversaries of other WWII milestones.

The retired railroad worker is a member of the Vancouver chapter of the Pearl Harbor Survivors Association, which holds its observance this morning.

Today’s event in Vancouver will be more low key than previous public events — the local association members will gather in a meeting room at the Red Lion Hotel at the Quay before launching a floral wreath into the Columbia River.

Bennett was only 17 when he first put on a Navy uniform. His parents died in a car crash when he was 6, and Bennett spent much of his boyhood moving from relative to relative.

“It was hard for me to adjust. I wasn’t doing good in school,” the 85-year-old veteran said. “I dropped out.”

His grandmother signed his enlistment papers so the 17-year-old could join the Navy. He fit in nicely.

“I had toyed around with radios, built my own crystal set. I learned Morse code in the Boy Scouts, and when I took the Navy test, I scored high in math.”

He became a radioman in the Navy’s aviation program. That’s what brought him to Pearl Harbor in September 1941, when he served with a seaplane squadron based on Ford Island. Their barracks were near “Battleship Row,” a primary target of the attackers.

Bennett was busy with the most mundane of military tasks that morning. He was shining his shoes, getting ready to head into town on liberty with a buddy, when he heard explosions.

“I looked out the window, and there was a Japanese plane,” he said.

Personnel were sent to fight a hangar fire at the seaplane base. But when the U.S.S. Arizona went down, “It severed the water line to Ford Island,” Bennett said. “We didn’t have anything to fight the fire.”

Or to drink. As they worked, an officer pointed to a nearby pop machine.

“He said, ‘Break that open so we can have a cold pop.’” Bennett said.

“There wasn’t any water that night for cooking, so the cooks boiled water from a swimming pool and made soup.”

It didn’t take long for the Navy to expand its air arsenal, bringing in heavy bombers. Bennett was assigned to the crew of a PB4Y, the Navy version of a B-24 Liberator. The radio operator sat right behind the pilots, where he also manned a machine gun turret.

Bennett’s bomber squadron, VB-101, left Hawaii in October 1942 and headed into the thick of the Pacific campaign.

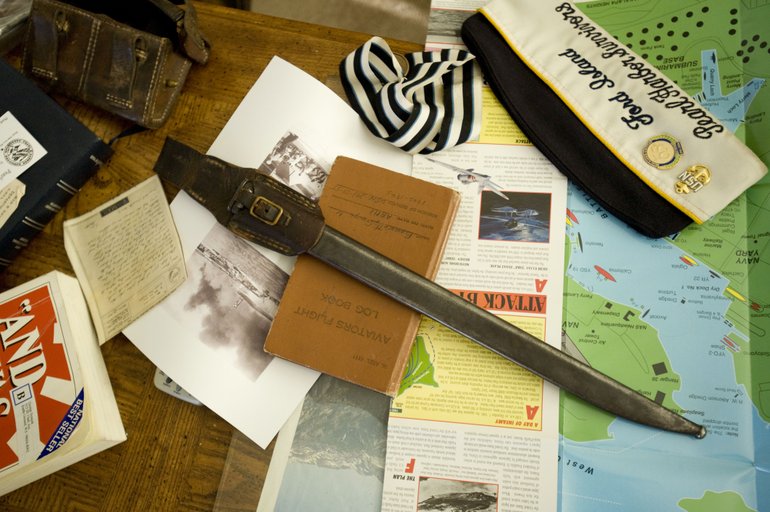

A pivotal step is recounted in Bennett’s flight log, although you wouldn’t know it by looking at it. The entry for that day’s flight reads: “Button to Cactus.”

“Button” was the code name for Espiritu Santo, part of the New Hebrides island chain.

“Cactus?” That was Guadalcanal, seized by U.S. forces after six months of fierce fighting.

Much of the island was littered with the debris of close-quarter combat when Bennett and a buddy took a look around. They hiked to the scene of some of the last Japanese resistance and came across a bunker. A bayonet was sticking up out of the ground. When Bennett started to grab it, his buddy warned: “No! It’s a booby trap!”

Bennett carefully looped a length of communication wire around the handle and gave the wire a yank. Nothing happened.

Bennett also came home with several Japanese rifles.

Another keepsake is a letter he had mailed to his grandmother. It illustrates the news soldiers and sailors were allowed to share with their families back home.

You couldn’t say what you’d done, what you’d seen, or where you were, Bennett explained.

The highlight of his letter was: “I’m starting to get a rash in spots on my legs and hips.”

Sixty-five years after penning those words, the survivor of Pearl Harbor, veteran of midnight bombing runs and participant in the world’s biggest conflict just smiled.

“What else am I going to say?”