o Researchers did not need to give monkeys extra food so they would have animals for the “obese” study group. Like humans, monkeys come in a variety of weights and shapes, said OHSU researcher Dr. Alison Edelman.

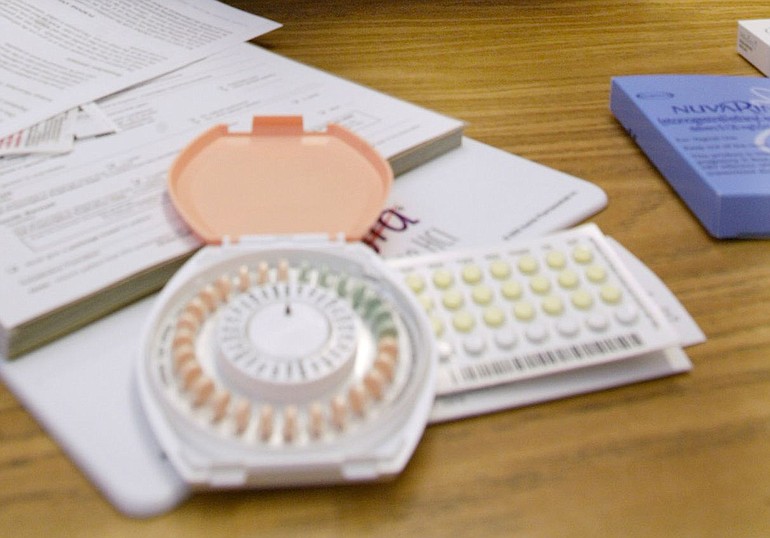

Women should not quit taking birth control pills just because they’re gaining weight, say researchers at Oregon Health & Science University.

Results of a study released Wednesday found no support for a common belief that oral contraceptives cause weight gain.

OHSU researchers working with two groups of monkeys found no weight gain in the normal weight group after the eight-month treatment. The obese group of monkeys actually lost weight.

“The No. 1 reason women discontinue contraceptive pills is a perceived weight gain,” said Dr. Alison Edelman, a physician and researcher in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at OHSU and lead author of the study. “It’s a commonly held belief.

“Adults gain weight as they get older. Women as well as men go through a lot of changes,” Edelman said. “Birth control pills are one of the most commonly used medications. If you have a weight gain, you blame something you take.”

The study will appear in next month’s edition of the journal Human Reproduction.

The results come with some qualifiers, Edelman noted.

This was not a human study, although the reproductive system of the rhesus monkeys used in the study is nearly identical to humans.

Researchers controlled the food supply, so “the animals stayed on a diet,” Edelman said.

“We looked at them for three months before the birth control pills, kept them on a weight-stable diet, and continued them on that” through the study.

Because of increasing obesity in the United States, “we added a cohort of obese monkeys,” she said. “We were fairly surprised by significant findings in the obese group.”

The obese monkeys lost about 8 percent of their body weight and 12 percent of their body fat during the test.

“We didn’t (forcibly) exercise them,” she added. Scientists did outfit all the animals with activity monitors — “almost like little necklaces,” she said.

“Like in humans, the heavy ones don’t move as much and ‘exercise’ less. That didn’t change with pill use,” she said. “What changed was basal metabolic rate: It increased, and it probably was due to birth control pills. That was the only thing that changed.”

And in another cautionary note, the study didn’t totally disprove the purported link between the pill and those extra pounds.

“But for normal weight women, there is fairly good evidence of not changing weight,” Edelman said.

That matches the results of similar studies, Edelman said.

“We realize that research in nonhuman primates cannot entirely dismiss the connection between contraceptives and weight gain in humans,” Judy Cameron, senior author of the paper, said in an OHSU news release. “But it strongly suggests that women should not be as worried as they previously were.”

Edelman said she will eventually move the research to human subjects, exploring relationships among health, diet and oral contraceptives.

“We already are studying women to look at weight and efficacy of birth control pills,” she said. Researchers hope to widen that study to include health effects in the next couple of years.

The research was funded by the Society of Family Planning.

“This is the first animal study they’ve sponsored,” Edelman said.

Tom Vogt: 360-735-4558; tom.vogt@columbian.com.