Penny owned her own business and lived in a fancy 4,000-square-foot home with a Lincoln Continental in the driveway.

Sheryl staggered into Vancouver with nothing but two kids and their bunk bed, a card table and a busted van seat for a sofa.

They came from different backgrounds but what they shared could easily have killed them both: booze-fueled traffic disasters and fist fights, delirium tremens and suicidal desperation.

But Penny and Sheryl are both friends of Bill W., and they say that friendship is what saved them.

“Friend of Bill W.” is code for a member of Alcoholics Anonymous. Bill W. means William Griffith Wilson, the Vermont man credited with starting AA in 1935, after he realized his extreme drinking habit was sure to destroy him.

What Bill W. started in Akron, Ohio, rapidly spread across the nation and around the world. Today there are an estimated 2 million Alcoholics Anonymous members in more than 100,000 different groups. According to the National Institute on Alcohol and Alcoholism, nearly 18 percent of Americans “abuse alcohol or are alcohol dependent.” If you’re a full-blown alcoholic, just deciding to cut back or dry out on your own rarely works, the Institute maintains.

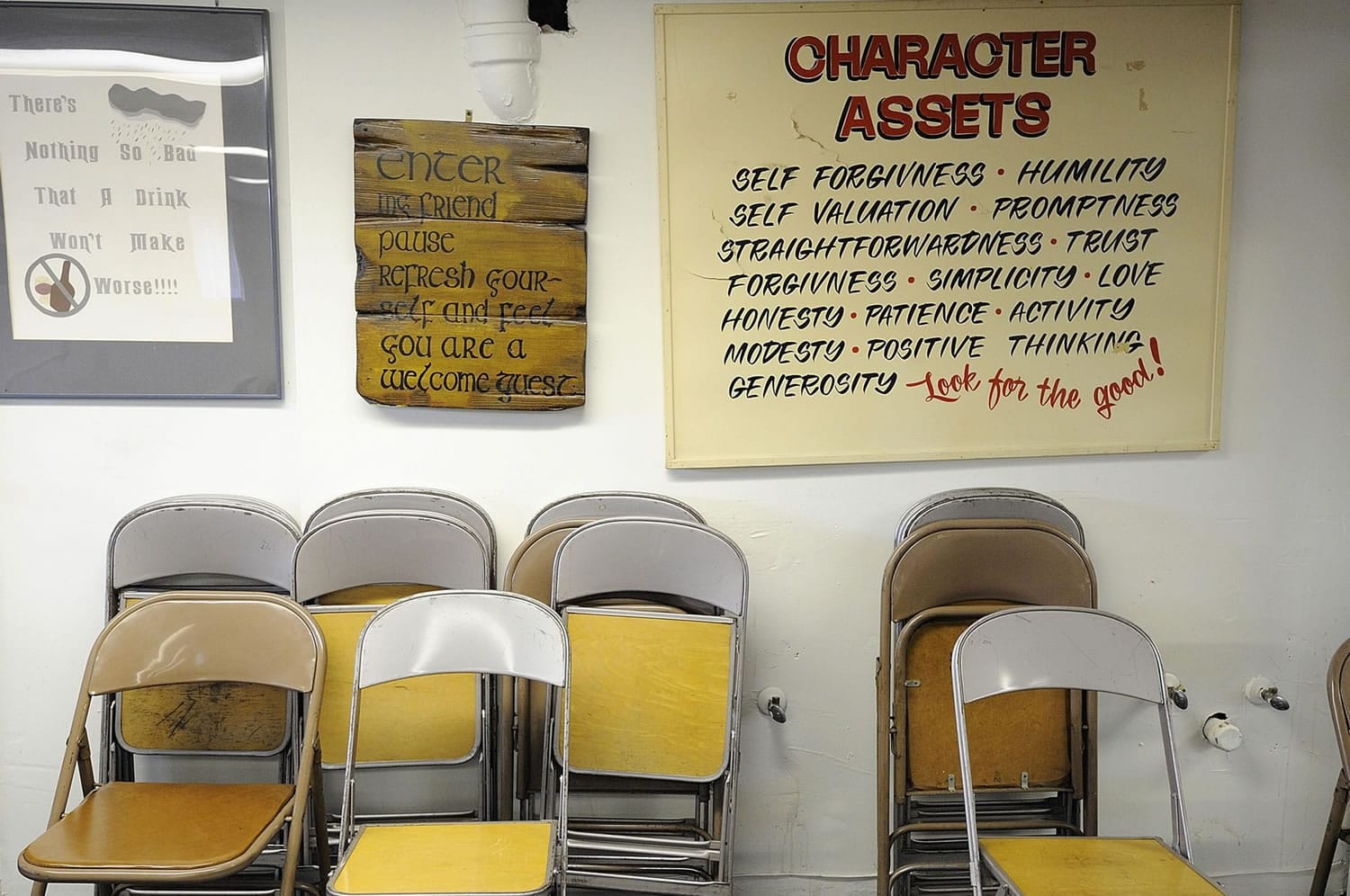

Visit the AA “Vancouver intergroup” website, http://www.vanintgrp.com, and you’ll find a schedule of literally hundreds of Alcoholics Anonymous meetings in the local area every week and at nearly every time of day — from “Early Birds” in a Camas church basement at 6:30 a.m., to a lunchtime “Sweatshop at the Y” at a gym in east Vancouver, to “candlelight” (9:30 p.m.), “starlight” (11 p.m.) and “moonlight” (12:30 a.m.) meetings held at the Lighthouse, a storefront church in central Vancouver.

There are women’s groups and men’s groups, a couple’s group and a newcomers’ group. There are non-English-speaking groups and one 24/7, doors-always-open group. There are groups that provide child care and groups dedicated to wheelchair accessibility. There’s a traveling group that convenes where disabled people live, and groups grappling with multiple addictions and worst-case scenarios — “Last Chance” groups.

AA members come from all walks of life, from doctors and lawyers and priests to bikers, jailbirds, housewives and high school students. The talk is tough, honest and absolutely private (first names, last initials only); the friendships and support networks formed are deep and lifelong.

Just witness the simpatico on display when Peggy and Sheryl get together at a Hazel Dell diner to talk about AA on the eve of its 65th anniversary in Vancouver.

“We’re just two drunks talking to one another. It’s that simple,” said Sheryl. “Nobody else can understand. People out there don’t understand who I am and what I am.”

But a chipper young waitress noticed the AA materials scattered around the table. “Are you friends of Bill W’s?” she asked with a grin. “I’m a friend of his, too.”

A historical celebration is set for 6 p.m. Sunday, June 5, at the Clark Public Utilities meeting room, 1200 Fort Vancouver Way. Penny will tell the story of the group and share some birthday cake.

Free advertising

“Alcoholics anonymous. Write Box 647, Vancouver.”

It was that succinct — just about as succinct as “friend of Bill W.” — when it first appeared in this newspaper on May 22, 1946. It was a nearly invisible classified ad buried among psychic-reading offerings, the lost-and-found column and Help Wanted: man to mow lawn.

According to a history of AA in Western Washington called “Our Stories Disclose,” a man named Jerry found himself unemployed after Vancouver’s wartime shipyards shut down. His family was worried about his desultory drinking. He began attending Portland’s 10th Street AA group and decided to bring the concept to Vancouver.

Jerry called the editor of The Columbian, who ran the ad several times for free. Just four men attended when the first Vancouver AA meeting was held in Howard’s living room on June 6, 1946. But within a few years there were as many as 21 showing up, so meetings rotated to different homes and then to the Gold Room of the Evergreen Hotel — one of the swankiest spots in town, at the time — for the discounted rate of $3 per meeting. If the hotel had a better-paying renter, AA was bounced to a bedroom where members sat on chairs, beds, radiators and the floor.

In 1950, according to “Our Stories Disclose,” the group was “startled” to receive a letter from a woman who wanted to come, too. “One entire Friday night meeting was spent discussing the pros and cons of allowing women in. Some members felt that others would become more interested in women than sobriety,” and group language might be too rough for the gentler sex. Others were “suspicious of her motives” — but Mildred was admitted on probation.

Apparently this brave lady did not ruin the group nor erode other members’ resolve, and she was accepted “as just another alcoholic seeking recovery,” the book says. Over the years, the group made many moves — among them what’s now the Memorial Health Center on Main Street, McLoughlin Junior High School, the Red Cross building near Officers Row and a spot on East Sixth Street downtown. Schisms and splinters occurred, with other groups forming and disbanding and a district system emerging to iron out geographic wrinkles.

How to believe

Meetings are the backbone of what AA does: offer peer support, compassion, community. Nothing’s more important when you’ve hit rock bottom, Sheryl and Penny said.

Sheryl, of Castle Rock, was 27 years old and the mother of two small children when she woke up in a hospital with 50 stitches in her face.

She’d been raised in a loving but very alcoholic home, she said, and started hitting the bottle hard when she was 15. She drank every day; she begged baby-sitting so she could hit the bars as early as possible. She subsisted on welfare and “filled my fridge with as much wine as I could buy,” she said. “I have seen the inside of a jail many times, I have wrecked cars … I have been in many fights with bruises and stitches, I have abused my children, been kicked out of my parents’ home, prostituted myself.”

This time, she’d totaled her car just one block from home. If her children had been with her, she realized, they could have been killed.

A friend who sat with her all night said: “Don’t you think it’s time you did something about that drinking problem?”

The judge told her: “If I ever see your face in my courtroom again, you will get put away for a long, long time.”

Sheryl went for inpatient treatment, packed up her kids and moved to Vancouver with nothing but a halfway determination to survive. She showed up at AA “not liking the smiles on their faces, not liking their laughter, not understanding what they were talking about. What was this higher power stuff?”

She was full of hatred and pain, she said. When she went to visit her parents, she felt too far gone for any higher power — “I didn’t know how to believe in God, I didn’t know how to believe in anything,” she said — so she went into the pasture and made her confession to the family cow.

That was 37 years ago, and she’s never had a drink since.

Half a cup

Penny came from an alcoholic family, too. She was operating her own business and living a luxurious married life — while heading for suicide.

One night in 1982, she was literally crawling out her door to go drive the wrong way down the freeway and jump off a bridge, if she made it that far. That was her plan — but she got “tangled up” in a telephone book on the floor, she said. The book fell open and the big black letters AA grabbed her attention. The ad said call any time, day or night, so she did.

She talked to someone named Joy. There were three days of constant phone calls, and Joy was always there for her.

Telling the tale over diner french fries, Penny choked up. That phone call saved her life and probably others’ too. If she’d carried out that wrong-way suicide mission, she said, who else might have died?

“I believe there are moments in time when God opens a window and you can come through,” she said. “That’s why that phone book was right there.”

She made it to an AA meeting so wasted and sick, she said, she couldn’t hold her head erect. A hot cup of coffee appeared before her, but her hands were too shaky to take it.

The coffee disappeared, then reappeared again, now only half-full. She could manage it now.

“That was the kindest thing anybody ever did for me,” Penny said. She wanted to drink for years. She lost her family but put her life back together. She went to multiple meetings daily. She hasn’t had a drink in 35 years.

Twelve steps

The well-known 12 steps undergirding Alcoholics Anonymous emphasize the healing power of God, and that’s clearly the right way for many — but Sheryl insisted that your higher power is whatever you want to make it (even a cow), including the power of a loving community that’s greater than yourself. “We have some agnostics,” she said.

“You begin to feel the amazing love in the room,” said Penny. “It’s a kindness you don’t know what to do with. A normal person can’t understand it.”

Here’s the American Psychological Association’s six-point summary of a 12-step program:

• Admitting that one cannot control one’s addiction or compulsion (step one).

• Recognizing a higher power that can give strength (two and three).

• Examining past errors with the help of a sponsor or experienced member (four through seven).

• Making amends for these errors (eight and nine).

• Learning to live a new life with a new code of behavior (10 and 11).

• Helping others who suffer from the same addictions or compulsions (12).

Helping others sometimes means responding to hot line calls for help and even rushing over to some despondent person’s home before something horrible happens. Sheryl and Penny shared “war stories” about rescue missions in flophouses and mansions, breaking down doors and opening windows in gas-filled rooms.

“The biggest thing is personal contact,” said Penny. “The biggest thing is when you sit with a person who’s in terrible pain and tell them they’re going to make it. And you know they will, because you remember when you were sure you couldn’t. But you did.”

Scott Hewitt: 360-735-4525 or scott.hewitt@columbian.com.