Publication features local memories – such as Pete Ritter’s boxing career

(Editor’s note: This is a condensed version of an article included in the “Clark County History” annual for 2010. See today’s story on page D1.)

My dad, Pete Ritter, was once a professional middleweight boxer. While very successful at it, he only boxed from 1930 to 1932. He never really talked about why he quit so soon, when he was only 22 years old, but later in this story the reason may become clear.

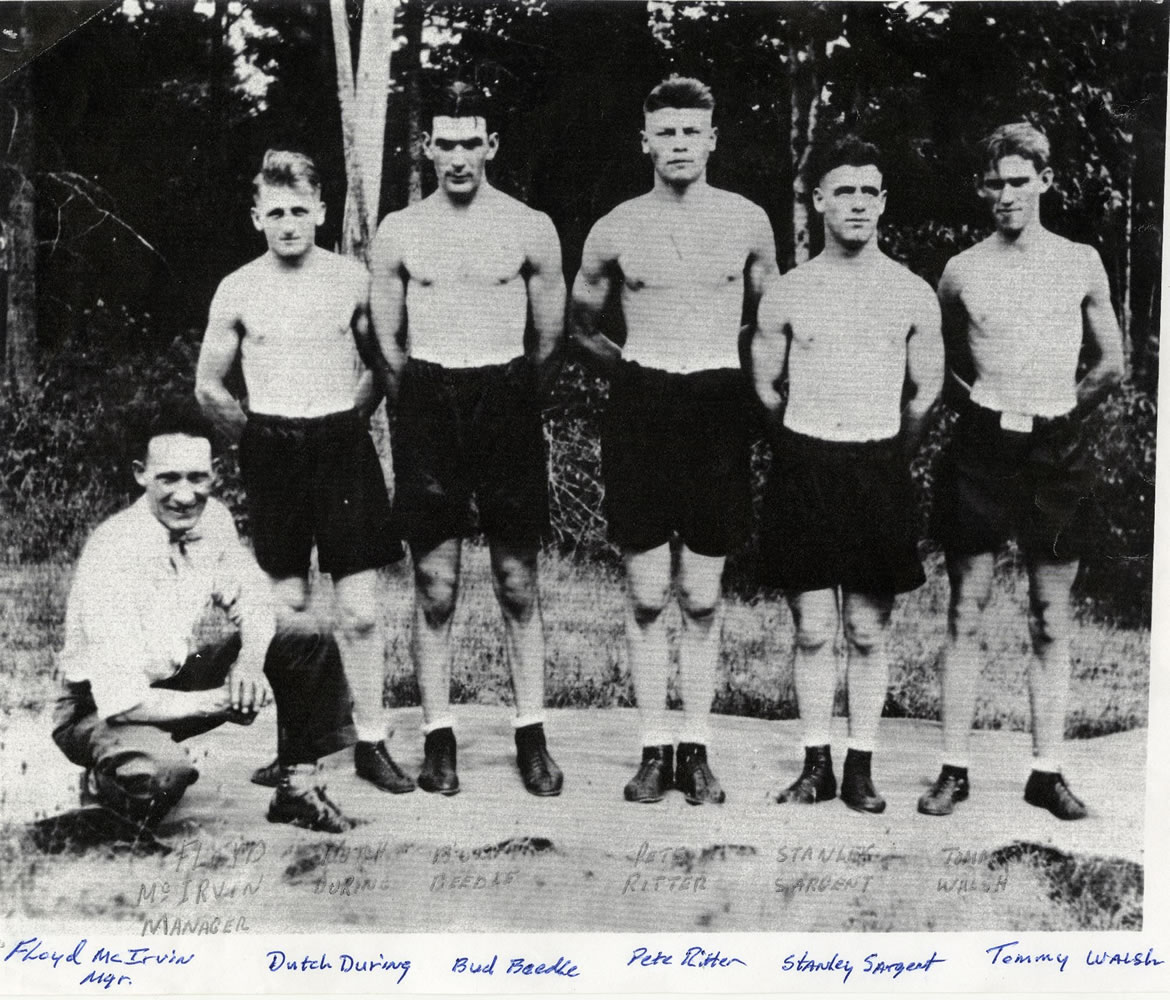

Pete’s manager was Floyd (Mac) McIrvin, who ran a stable of fighters in Vancouver and, outside of Vancouver Barracks, may have been the town’s only fight manager at the time. Besides my dad, his stable included Percy (Bud) Beedle, Roland (Dutch) Douring, Stanley Sargent, Tommy Walsh, Fred Gallas and sometimes Brick Coyle. Beedle, Ritter and Sargent worked together at the S. P. & S. Railway. They worked by day, trained by night and were close friends.

Pro boxing was hardly a way to get rich. The largest purse Pete ever received was $60 for a return match with Cowboy Brooks in the Oregon Middleweight Tournament. His gross career earnings were $334. His manager, Mac, took $104.50, leaving Pete’s net earnings at $229.50. For 15 bouts, that works out to $15.30 per fight, or about two day’s wages for a laborer during the Great Depression.

The only arena that featured pro boxing in Vancouver was the Victory Theater at Vancouver Barracks. Seating capacity was around 650, and the price of admission was geared toward a soldier’s small income. Ticket prices were $1, 75 cents, 50 cents, and boys 12 and younger could get in for 25 cents.

Judging by newspaper clippings from the period, the middleweight division seemed to have the most competition. There were a few light heavyweights, but there was no mention of heavyweights in Southwest Washington or the Portland area. Men simply were not as big then as they are today, or maybe they just worked hard while triple-cheeseburgers were not yet popular.

Pete Ritter’s third pro fight was in Woodland on April 10, 1930. He was scheduled to fight a man with similar boxing experience, but he just didn’t show up. As the fight was supposed to get underway, Pete was told they had found a replacement. His opponent would be Nort Rogers — a well-known tough guy with plenty of ring experience and a lot of wins.

Pete’s immediate reaction was something like, “You’re crazy, I ain’t fightin’ him.”

Manager Mac calmly responded, “Just get in there, do the things we’ve been working on, and don’t get yourself hurt.”

Through all four rounds, Nort and Pete did everything in their power to hurt each other but the fight ended in a draw. Nort and Pete would meet again 18 years later after their sons became school pals and managed to get their dads back together. That meeting resulted in a win for both men: a lifelong friendship between the two families.

After the Nort Rogers fight, Pete began a string of knockout victories, earning him the nickname, “The Mighty Mauler.”

Fatal fight

The Oregon Middleweight Championship Tournament began in April 1931, and Mac’s fighters held their own through the month of May. The main event on June 9, 1931, featured Stanley Sargent from Vancouver and Pete Meyers of San Francisco. It was Meyers’ first fight in the area, and he brought with him an impressive knockout record. In the fight prior to the main event, Pete Ritter knocked out Jimmy Clark in the fourth round for his third consecutive win in the tournament. It was going to be a good night for the Vancouver boys, or so they thought.

Sargent knocked Meyers down for a five count in the first round. Through the first minute of round five, most people figured Sargent was winning the battle. Then there was a left-hand punch that dropped Sargent to the canvas, but he bounced up before there was a count and pursued Meyers. As Meyers neared the neutral corner, he turned and was apparently surprised to see his tipsy opponent right in front of him. He reacted quickly with a solid right to Sargent’s chin, causing him to drop backwards and land head first.

The thud of his head hitting the canvas could be heard in the upper seats in the auditorium. Referee Bud Oliver didn’t even start the count; he just raised Meyers’ hand and bedlam ensued.

Fans mobbed the ring as Sargent was taken to the dressing room. About 45 minutes later, he was taken to Good Samaritan Hospital, where doctors worked on him through the night. Around 6:30 a.m., surgery was performed to relieve pressure on his brain. He never regained consciousness and died around 1:25 p.m., just minutes after his father arrived at the hospital.

Final match

Through the summer and fall of 1931, Pete Ritter may have considered himself retired from boxing. However, since he was undefeated and a local favorite, there was enough pressure on him to agree to another fight.

On New Year’s Day 1932, Pete fought light heavyweight Dave Humes at the Portland Auditorium. The fight ended in a draw. Shortly after the fight, Pete announced he was finished with boxing. When reporters questioned him, his response was he didn’t feel his wind was good enough to compete at higher levels. Of his 15 fights, he had won 10 by knockouts, but fans who had followed his career noticed something quite different in his last two fights: after Sargent’s death, Pete had lost his “killer instinct.”

Pete Ritter became an engineer for the S. P. & S. Railway (later Burlington Northern Santa Fe). He was less than four years away from retirement when he was killed in the line of duty near Bend, Oregon, on July 16, 1971, at age 61.

EVERYBODY HAS A STORY welcomes nonfiction contributions and relevant photographs. E-mail is the best way to send materials so we don’t have to retype your words or borrow original photos. Send to neighbors@columbian.com or P.O. Box 180, Vancovuer WA 98666. Questions? Call Scott Hewitt at 360-735-4525.