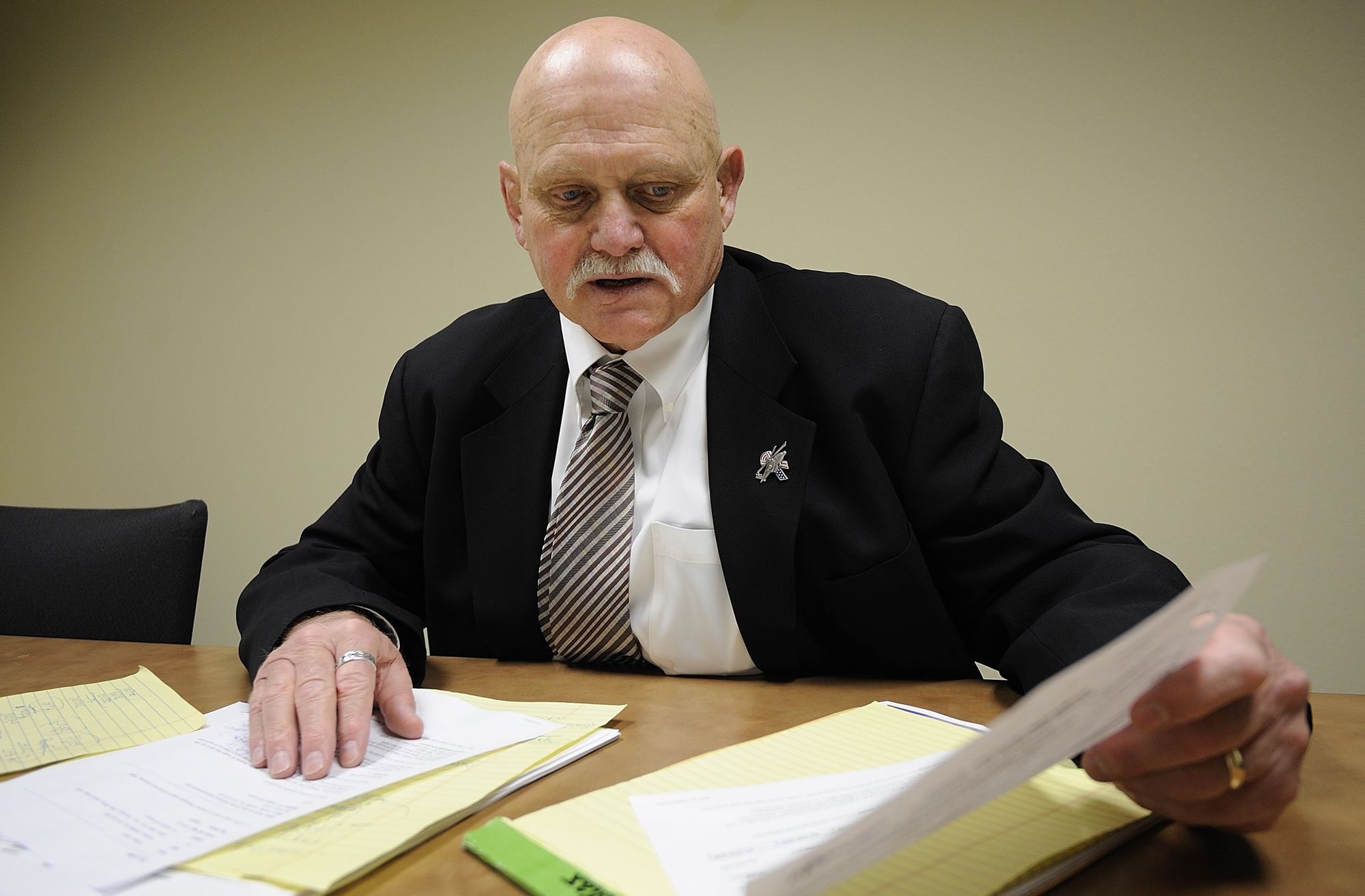

With retirement comes reflection, and Cleve Thompson, who retired last week as Clark County’s drug and alcohol program manager, can look back on significant accomplishments. He:

• Secured inpatient beds so Vancouver residents would not have to go as far as Sedro-Woolley or Spokane for residential treatment.

• Successfully lobbied — making a key phone call to a U.S. senator — for the $39 million Center for Community Health, which required unprecedented cooperation among local, state, federal and tribal governments and nonprofit agencies to consolidate services.

• Pitched the idea for a drug court for nonviolent addicts to Clark County Superior Court judges. The pilot project, in which defendants committed to treatment could stay out of jail, proved so successful the county now has seven targeted therapeutic courts including ones for veterans, juveniles and the mentally ill.

As people praise Thompson, 63, as a champion advocate and master grant writer who built the infrastructure for substance abuse treatment in Clark County, they acknowledge a lot of the services he’s fought so hard for could be gone by the end of the year.

Because while retirement calls for reflection, a $1.4 billion state budget shortfall calls for reality:

• The state Department of Social and Health Services has proposed to meet a 10 percent budget reduction by, among other things, eliminating “all alcohol and substance abuse services for adults” with the exception of pregnant women and mothers whose children are younger than 1. That would affect more than 55,000 people statewide.

• Depending on the state cuts, Clark County Commissioner Marc Boldt said the county might have to redirect money from therapeutic courts to pay for inpatient treatment.

• Lynn Samuels, executive director at Lifeline Connections, the county’s only inpatient substance abuse treatment center, said if the state stops paying for low-income/indigent people she’d lose approximately one-quarter of patients, lay off as many as 35 employees and give up some of her space at the Center for Community Health.

Approximately 6,500 people, including those with private insurance, are treated at Lifeline Connections a year.

Thompson earned $80,640 a year; his position will not be filled.

A co-worker in Clark County’s Community Services Department, youth program manager DeDe Sieler, will pick up Thompson’s duties, including managing three federal grants.

“What I learned from Cleve is you have to be great partners with community providers,” she said. “And your one and only goal is to capture, garner or leverage as much funding for our community as possible.”

It’s too soon to tell what exactly will come out of the special legislative session, set to convene Nov. 28.

By then, a second negative revenue forecast will likely have been released.

“My only option is across-the-board cuts,” Gov. Chris Gregoire said Sept. 22.

She hopes to finalize a budget, with healthy reserves, before Christmas. She’s asked state agencies to prepare budgets with 5 to 10 percent cuts.

Since the national recession began, the state has made nearly $10 billion in cuts, according to Gregoire’s office.

Since 2007, Thompson has lost 40 percent of his state funding, from $12.8 million in the 2007-09 biennial budget to $7.7 million in the 2011-13 budget. State funding currently accounts for 65 to 70 percent of his budget. After the next round of cuts the number will likely drop to less than $500,000 a year. The county would also lose Medicaid dollars, as it currently gets 50 cents for every $1 the state pays for alcohol and drug treatment.

Clark County commissioners don’t know how they are going to continue offering services in light of the state cuts, and said last week they want to lobby state lawmakers to consider alternatives to cutting money for treatment.

State Rep. Jim Moeller, D-Vancouver, said there aren’t any easy cuts to make.

“Everything is on the table,” Moeller said. “We have to have a balanced budget.”

Costly mess

Thompson knows from his 19 years with the county that cutting funding for treatment will shift costs elsewhere, and the government already pays far more for cleaning up the mess caused by addiction than it does for getting people help.

“We’re at the tipping point right now, where we’re going to see the loss of resources,” Thompson said. Drug and alcohol services have fallen behind mental health services because of a surge in advocacy for the mentally ill; there’s crossover in the populations and Thompson sees both services as essential.

“There’s a lot of stigma,” he said of addicts. “People think they can change by themselves, ‘Just pull up your bootstraps and stop.’ It’s not so easy once you are addicted.”

Thompson first observed the consequences of addiction in his previous career. He spent two decades in public education, first as a teacher, then as an assistant principal in Roseburg, Ore. As assistant principal, he was in charge of security and discipline. (“I flushed a lot of chew down the toilet,” he said.)

“Ten percent of the families take 90 percent of your time,” he said. The students caught with tobacco or alcohol typically came from families where one or both of the parents had substance abuse or mental health issues.

He spent the majority of his time dealing with the fallout from addiction; governments spend accordingly.

A 2009 study by the National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse examined how government spends money related to substance abuse — prevention, treatment and the morning-after consequences.

Columbia University researchers broke it down this way: For every $100 spent by the state of Washington in 2005 on drugs, alcohol and related costs, $2.81 of that $100 was spent on prevention, treatment and research.

The amount spent “shoveling up” the mess (crime, health and social services related to addiction) was $85.34.

The balance was spent regulating state-operated liquor stores.

“I learned early on it’s a rationed system,” said Thompson. “We treat about 20 percent of the need in the community … if I knew money was being underused (in the state) I would figure out how to get it.”

When addicts go untreated, they burden the health care, criminal justice and social service systems, Thompson said.

“If we didn’t have detox, they would be in the ER, jail or squad car,” he said.

Unequal funding

When Thompson came to the county in 1992, people detoxing from drug or alcohol addiction had nowhere to go but a hospital; people in need of a longer inpatient stay were sent to Yakima, Spokane or Sedro-Woolley, north of Everett.

While other counties of Clark’s size were funded at $5 to $6 per capita for detox treatment, Clark had fallen far behind.

“We were funded at $1.13 per capita,” Thompson recalled.

During a state meeting with his counterparts, everyone agreed it wasn’t fair, he said, but nobody wanted to give up money. Thompson suggested the highest rates would be frozen, and new dollars would be distributed to Clark and other underfunded counties. It worked.

“They thought I knew something about funding formulas,” he laughed.

Another one of his major achievements was his work on the Center for Community Health.

In 1997, Clark County sold property to Clark College, displacing headquarters for what was then the Southwest Washington Health District and other social service agencies.

At the same time, the county’s Department of Community Services was starting to work with the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs to better serve veterans.

Thompson remembers sketching on a sheet of paper a rough idea for what became the four-story Center for Community Health, 1601 E. Fourth Plain Blvd.

It took years of negotiating to get local, state, federal and tribal governments, as well as the nonprofit service providers, under one roof. While the project was still in the planning stages, there was moment of panic when then-U.S. Secretary of Veterans Affairs Anthony Principi said he was not going to commit to any new projects.

For the deal to work, the VA would have to lease property to the county.

Thompson made a call to U.S. Sen. Maria Cantwell, D-Wash.

“She was able to do what senators do,” Thompson said. “It was approved the next day.”

Initiated drug court

Comparatively, getting Clark County Superior Court to start a pilot drug court in 1999 was simple. He gave judges a presentation on drug courts, where nonviolent addicts stay out of jail as long as they are committed to treatment and comply with other terms. It was modeled after a program started in Florida’s Dade County (home of drug-plagued Miami) in 1989.

Only Judge James Rulli was willing to try it.

Rulli started a court for nonviolent felony drug offenders; a similar program was started in District Court for misdemeanor offenders.

Through 2010, 346 people have graduated from felony drug court.

The 33 people who graduated last year, by avoiding county jail and state prison terms, saved the county and the state a total of $830,000.

Of felony drug court graduates, recidivism rates at five years post graduation is 17 percent; similar offenders who do not go through treatment court have a five-year recidivism rate of 62 percent.

Also last year, nine babies were born drug-and-alcohol free to drug court graduates.

The county expanded the model, and its seven specialty courts include a Family Treatment Court, for parents trying to reunite with their children, a Juvenile Recovery Court for youth addicts and a Veterans Therapeutic Court.

The veterans court, which received a three-year federal grant of $350,000, was started because 89 percent of military veterans booked into the Clark County Jail admitted to having substance abuse problems.

In addition to spearheading treatment courts, Thompson always managed to find the funding, Rulli said.

“That’s why he’s going to be so sorely missed, because in these times it’s going to be even more difficult to try to find funding,” Rulli said. “It’s all so up in the air.”

Rulli added that even skeptics on the Superior Court bench have come around to endorse treatment courts.

“Many studies have verified it’s simply the best way to spend money.”

Vancouver resident Ken Jennings, a drug court graduate, will celebrate nine years of sobriety in November.

Jennings, 42, was first booked in the Clark County Jail when he was 18. Two dozen arrests later, he signed up for drug court. He went on to serve on the county’s Substance Abuse Advisory Board, but hasn’t been able to attend meetings since he started a swing shift at a Portland steel mill.

He and his wife have a blended family of seven children.

When he first signed up for drug court, he had an aversion to authority figures. But Thompson drew him out, and later encouraged him to tell his story in Olympia to lawmakers who weren’t convinced drug courts could work.

“They think that drug court is a ‘hug a thug’ program,” Jennings said.

Without drug court, “I’d either be dead or in jail, that’s for sure. I believe that with all my heart.”

Thompson helped him not only with sobriety, but to become a better father.

“If you times that by the thousands of people he’s helped, I don’t know how anyone could come up with a word or a sentence or a paragraph to describe what he’s done,” Jennings said.

While retired, Thompson doesn’t plan to stop being an advocate, and will continue to let lawmakers know they need to fund treatment.

Despite the constant fighting for money, he said it’s been a wonderful job.

True, he’s seen relapses — “that’s part of the recovery process” — and received heartbreaking calls about addicts who accidentally overdosed or committed suicide.

But triumphs, such as Jennings, have kept him going.

Samuels, of Lifeline Connections, said Thompson was the best at securing grants because he worked the hardest.

“For Cleve, he always thought, ‘Well, if my staff and I do extra work, that’s one more person who can get treatment who wouldn’t get it otherwise.’”

Stephanie Rice: http://www.facebook.com/reporterrice; http://www.twitter.com/col_clarkgov; stephanie.rice@columbian.com.