Picture two television screens. One looks down on a chaotic city street and a car in flames — a scene of unrest, violence and danger.

Here’s another view from the same spot: A slightly upward-tilted lens reveals a calm, inviting cityscape on a gorgeous spring day. The burning car is the exception, not the rule. The whole scene serves as reassurance to a scared populace: things are really OK, and it’s time to get out there and march.

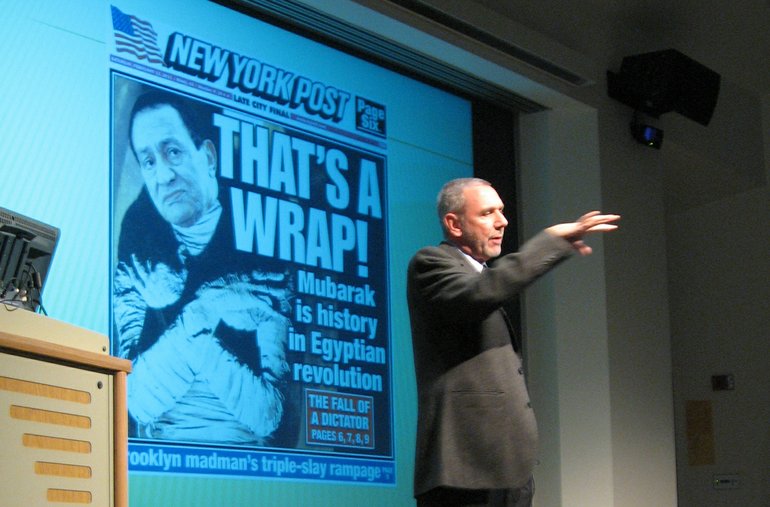

The first view of Cairo was broadcast by Egyptian government television one day during the recent revolution there, according to journalist and author Lawrence Pintak of the Edward R. Murrow College of Communication at Washington State University in Pullman. He spoke at the Salmon Creek campus Wednesday.

The second view was broadcast by Al Jazeera, the Arabic satellite news channel whose mission, simply put, is to “stir things up,” Pintak said. Al Jazeera even split its screen and displayed both pictures of reality — the tiny, scary one and the bigger, hopeful one — so viewers could get a taste of how easy it is to be fooled, and how their own government was trying to fool them.