SEATTLE — The grass is no greener. But, finally, it’s legal — at least somewhere in America. It’s been a long, strange trip for marijuana.

Washington state and Colorado voted to legalize and regulate its recreational use last month. But before that, the plant, renowned since ancient times for its strong fibers, medical use and mind-altering properties, was a staple crop of the colonies, an “assassin of youth,” a counterculture emblem and a widely accepted — if often abused — medicine.

On the occasion of Thursday’s “Legalization Day,” when Washington’s new law took effect, here’s a look back at the cultural and legal status of the “evil weed” in American history.

In the colonies

George Washington and Thomas Jefferson both grew hemp and puzzled over the best ways to process it for clothing and rope.

Indeed, cannabis has been grown in America since soon after the British arrived. In 1619 the Crown ordered the colonists at Jamestown to grow hemp to satisfy England’s incessant demand for maritime ropes, Wayne State University professor Ernest Abel wrote in “Marihuana: The First Twelve Thousand Years.”

Hemp became more important to the colonies as New England’s own shipping industry developed, and homespun hemp helped clothe American soldiers during the Revolutionary War. Some colonies offered farmers “bounties” for growing it.

“We have manufactured within our families the most necessary articles of clothing,” Jefferson said in “Notes on the State of Virginia.” “Those of wool, flax and hemp are very coarse, unsightly, and unpleasant.”

Jefferson went on to invent a device for processing hemp in 1815.

Taste the hashish

Books such as “The Arabian Nights” and Alexandre Dumas’ “The Count of Monte Cristo,” with its voluptuous descriptions of hashish highs in the exotic Orient, helped spark a cannabis fad among intellectuals in the mid-19th century.

“But what changes occur!” one of Dumas’ characters tells an uninitiated acquaintance. “When you return to this mundane sphere from your visionary world, you would seem to leave a Neapolitan spring for a Lapland winter — to quit paradise for earth — heaven for hell! Taste the hashish, guest of mine — taste the hashish.”

After the Civil War, with hospitals often overprescribing opiates for pain, many soldiers returned home hooked on harder drugs. Those addictions eventually became a public health concern. In 1906, Congress passed the Pure Food and Drug Act, requiring labeling of ingredients, and states began regulating opiates and other medicines — including cannabis.

Folklore and jazz clubs

By the turn of the 20th century, cannabis smoking remained little known in the United States — but that was changing, thanks largely to The Associated Press, says Isaac Campos, a Latin American history professor at the University of Cincinnati.

In the 1890s, the first English-language newspaper opened in Mexico and, through the wire service, tales of marijuana-induced violence that were common in Mexican papers began to appear north of the border — helping to shape public perceptions that would later form the basis of pot prohibition, Campos says.

By 1910, when the Mexican Revolution pushed immigrants north, articles in the New York Sun, Boston Daily Globe and other papers decried the “evils of ganjah smoking” and suggested that some use it “to key themselves up to the point of killing.”

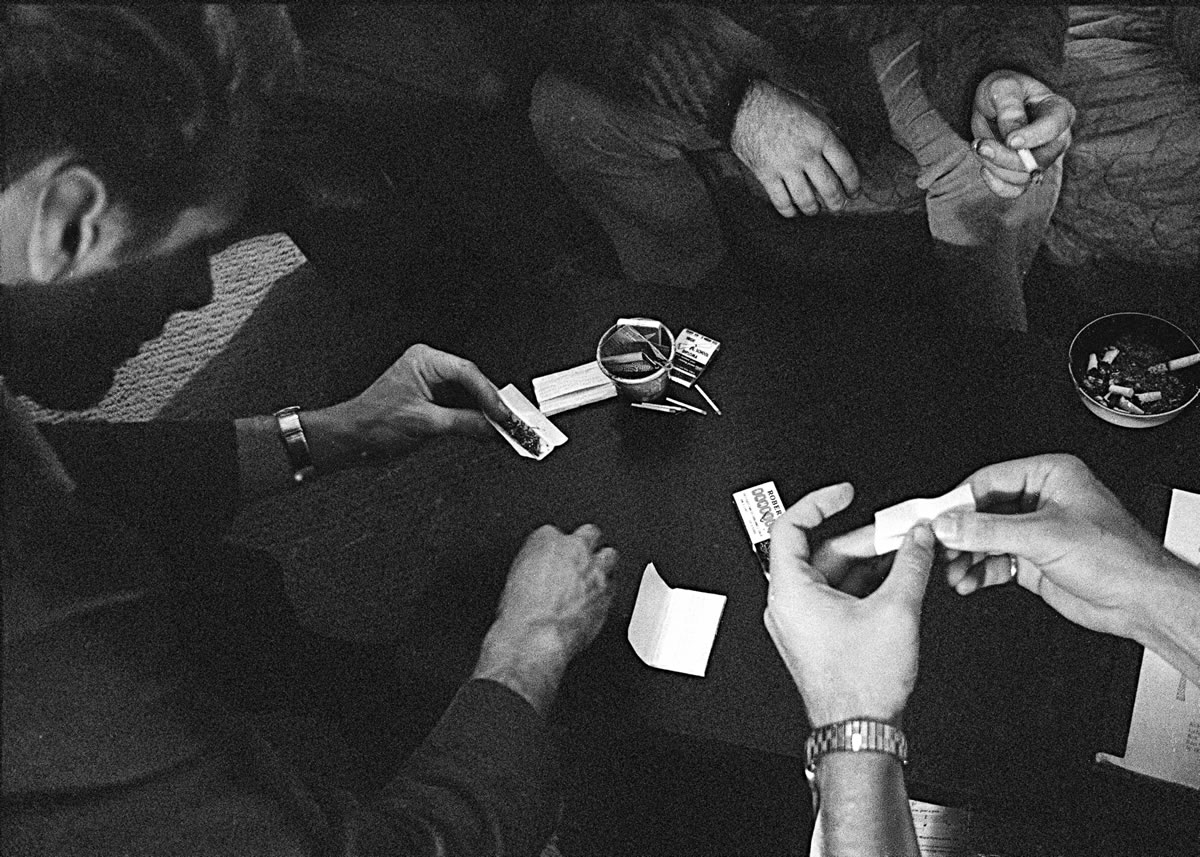

Pot-smoking spread through the 1920s and became especially popular with jazz musicians. Louis Armstrong, a lifelong fan and defender of the drug he called “gage,” was arrested in California in 1930 and given a six-month suspended sentence for pot possession.

“It relaxes you, makes you forget all the bad things that happen to a Negro,” he once said. In the 1950s, he urged legalization in a letter to President Dwight Eisenhower.

Reefer madness

After the repeal of alcohol prohibition in 1933, Harry Anslinger, who headed the federal Bureau of Narcotics, turned his attention to pot. He told of sensational crimes reportedly committed by marijuana addicts. “No one knows, when he places a marijuana cigarette to his lips, whether he will become a philosopher, a joyous reveler in a musical heaven, a mad insensate, a calm philosopher, or a murderer,” he wrote in a 1937 magazine article called “Marijuana: Assassin of Youth.”

The hysteria was captured in the propaganda films of the time — most famously, “Reefer Madness,” which depicted young adults descending into violence and insanity after smoking marijuana. The movie found little audience upon its release in 1936 but was rediscovered by pot fans in the 1970s.

Congress banned marijuana with the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937. Anslinger continued his campaign into the ’40s and ’50s, sometimes trying — without luck — to get jazz musicians to inform on each other. “Zoot suited hep cats, with their jive lingo and passion for swift, hot music, provide a fertile field for growth of the marijuana habit, narcotics agents have found here,” began a 1943 Washington Post story about increasing pot use in the nation’s capital.

Congress responded to increasing drug use — especially heroin — with stiffer penalties in the ’50s. Anslinger began to hype what we now call the “gateway drug” theory: that marijuana had to be controlled because it would eventually lead its users to heroin.

Then came Vietnam. The widespread, open use of marijuana by hippies and war protesters from San Francisco to Woodstock finally exposed the falsity of the claims so many had made about marijuana leading to violence, says University of Virginia professor Richard Bonnie, a scholar of pot’s cultural status.

In 1972, Bonnie was the associate director of a commission appointed by President Richard Nixon to study marijuana. The commission said marijuana should be decriminalized and regulated. Nixon rejected that, but a dozen states in the ’70s went on to eliminate jail time as a punishment for pot arrests.

‘Just say no’

The push to liberalize drug laws hit a wall by the late 1970s. Parents groups became concerned about data showing that more children were using drugs, and at a younger age. The religious right was emerging as a force in national politics. And the first “Cheech and Chong” movie, in 1978, didn’t do much to burnish pot’s image.

When she became first lady, Nancy Reagan quickly promoted the anti-drug cause. During a visit with schoolchildren in Oakland, Calif., as Reagan later recalled, “A little girl raised her hand and said, ‘Mrs. Reagan, what do you do if somebody offers you drugs?’ And I said, ‘Well, you just say no.’ And there it was born.”

By 1988, more than 12,000 “Just Say No” clubs and school programs had been formed, according to the Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation and Library. Between 1978 and 1987, the percentage of high school seniors reporting daily use of marijuana fell from 10 percent to 3 percent.

And marijuana use was so politically toxic that when Bill Clinton ran for president in 1992, he said he “didn’t inhale.”

Meds of different sort

Marijuana has been used as medicine since ancient times, as described in Chinese, Indian and Roman texts, but U.S. drug laws in the latter part of the 20th century made no room for it. In the 1970s, many states passed symbolic laws calling for studies of marijuana’s efficacy as medicine, although virtually no studies ever took place because of the federal prohibition.

Nevertheless, doctors noted its ability to ease nausea and stimulate appetites of cancer and AIDS patients. And in 1996, California became the first state to allow the medical use of marijuana. Since then, 17 other states and the District of Columbia have followed.