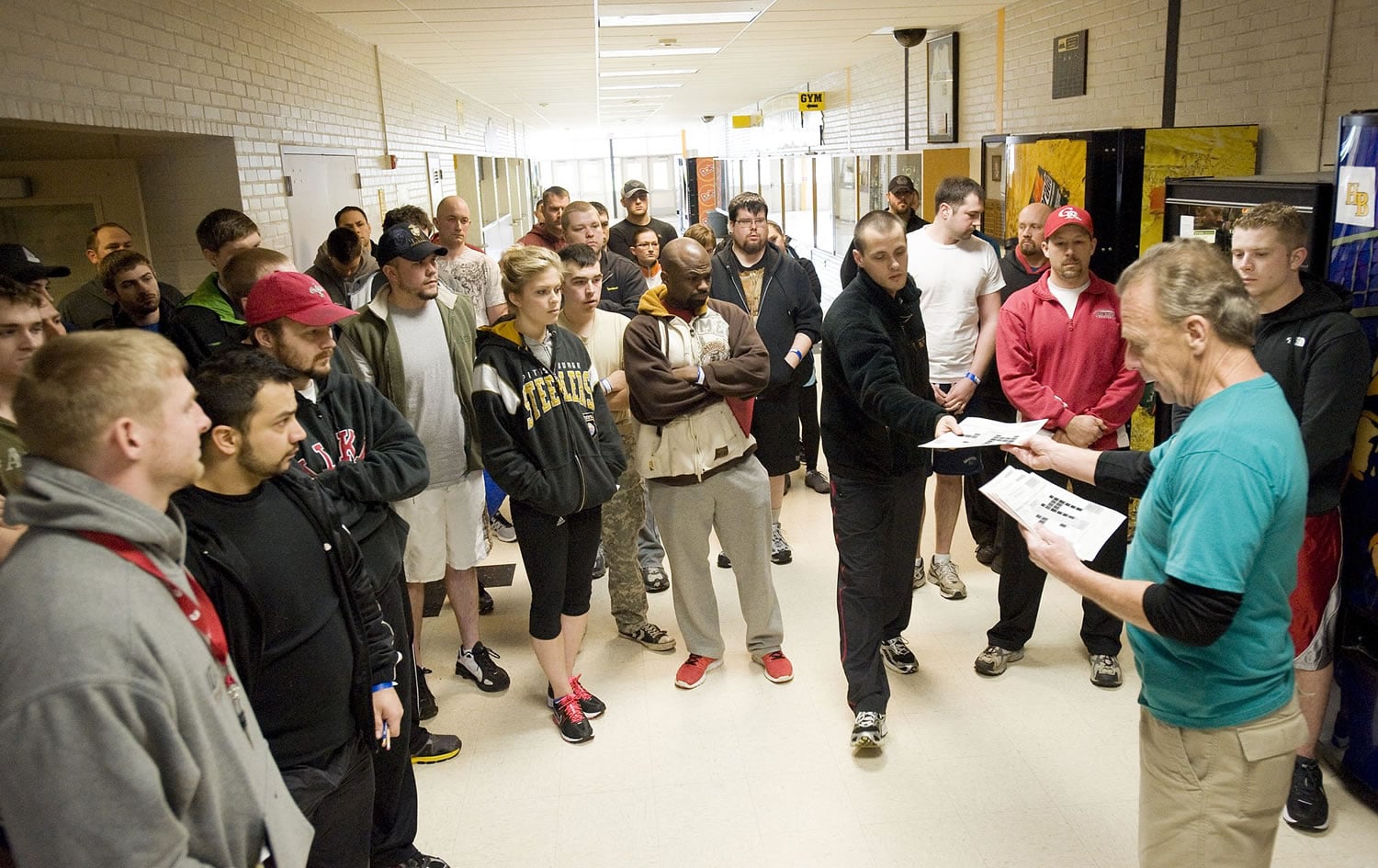

As he stood in the Hudson’s Bay High gym, a spot that on a recent Sunday was acrid with sweat and full of more than 160 men and women hoping to qualify for public safety jobs, Shaun Brooks was the rare exception.

While he was surrounded by nervous faces, Brooks, 25, said he wasn’t worried at all. Ahead was a timed 1.5-mile run, a 300-meter sprint, situps and pushups. But Brooks trained for more than three months and flew more than 1,000 miles from his home in Vail Valley, Colo., to get here. He was sure he’d eventually score a job with the Vancouver or Battle Ground police.

“It’s not nerve-wracking to me,” the married father of two and former corrections officer said. “I’m just going to go out and give it everything I’ve got.”

But before he can even hope to pin on a badge, Brooks and his fellow candidates have a long wait ahead hiring a few good men (and women) is a costly and lengthy process. It’s easy to imagine that once an agency decides to hire new police, it won’t be long before new hires are walking a beat. In reality, it can take years and cost hundreds of thousands of dollars.