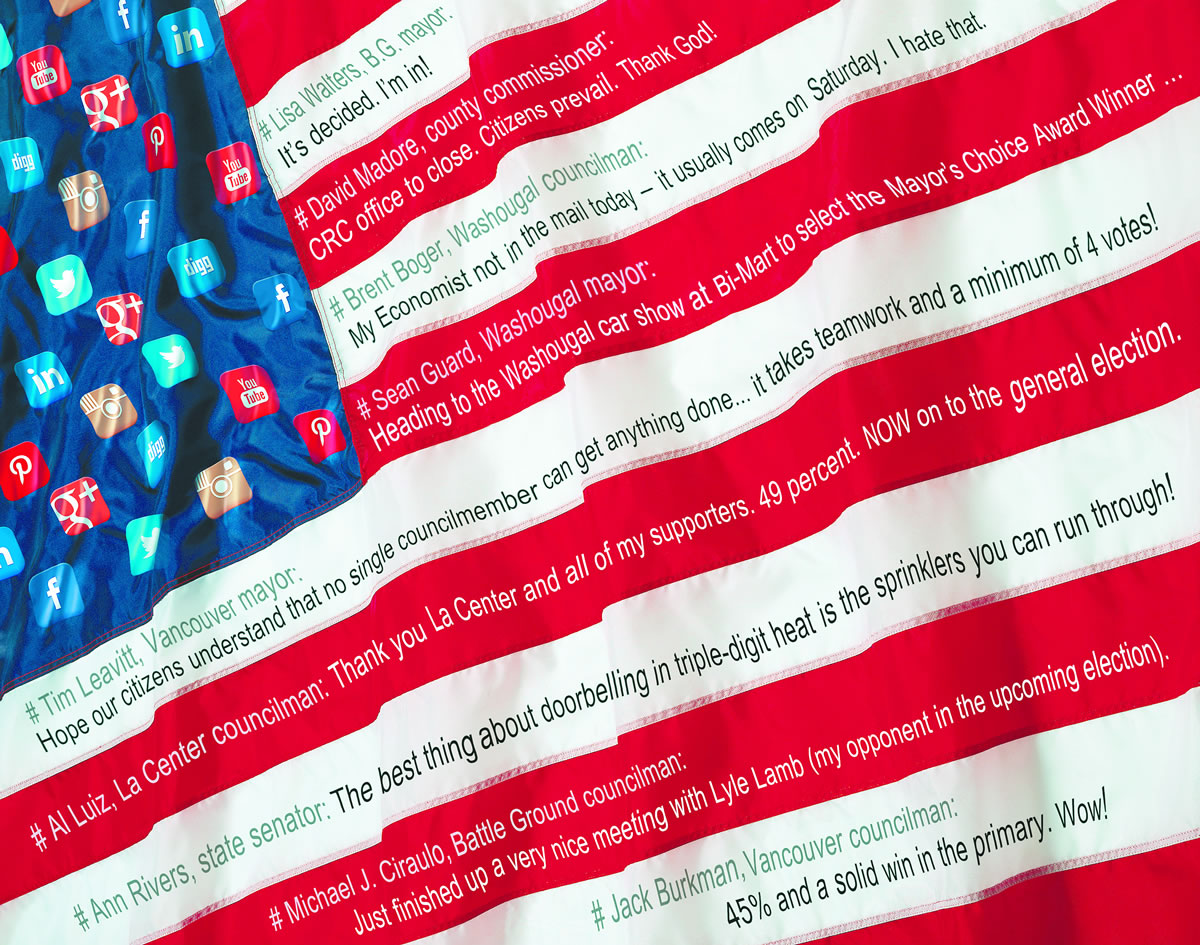

On any given day, Washougal Mayor Sean Guard checks his Facebook account a handful of times.

His online compulsion, so to speak, draws him to the social media site to drop words of wisdom, offer shout outs to emerging businesses and occasionally throw some jagged elbows at his political opponents. By now his daily Facebook posts come as second nature, even though no one would confuse him for the second coming of Steve Jobs.

“I am one of the most computer illiterate people around,” Guard said. “I don’t think I know how to change my photo on Facebook.”

Still, since Guard started using the social network in 2009, the onetime computer neophyte has racked up 1,241 friends. Today, he views social media not just as an important tool — but a necessary and, at times, dangerous one.

And he’s not alone.

The prevalence of Facebook and micro-blogging sites such as Twitter and little-used Tumblr have created a Brave New World for politicians, even those with previously Luddite tendencies. For Guard, and other public officials, it’s a way of communicating directly with constituents.

Studies show that around 72 percent of Americans are on social media. With more than 1 billion active users worldwide, Facebook has moved beyond its early days, when it was a connecting point for college students and a repository for photos of creative drinking practices. It has become, essentially, the Internet within the Internet, linking all aspects of the online world together and creating both a sounding board and connecting point.

According to a 2012 Pew Internet and American Life Study, 66 percent of social media users, or 39 percent of all Americans, have used social media to engage in a form of civic or political activity. The study found that social media users who talk about politics on a regular basis are the most likely to use social media for civic or political purposes.

The study concluded that 38 percent of users of social networking sites use the media to promote, or “like,” posts related to politics with which they identify.

Michael Rabby, a communications instructor specializing in social media at Washington State University Vancouver, considers social media a timesaver for politicians.

“At the local level, it’s an easier means of communicating than going door to door,” Rabby said. “And it’s certainly less invasive.”

But the rise in politicized social media also creates what’s known as a silo effect. People take partisan sides from which they don’t deviate and only follow politicians with whom they agree, Rabby said.

Washougal Councilman Brent Boger has a sizable Facebook presence — 2,397 friends and counting. He muses on local politics, as well as broader issues, such as the tenets of classical liberalism.

Boger has a very simple rule for his Facebook page: Keep it interesting. He’s aware of just how many “likes” each of his posts receives.

Of social media, Boger said it allows people to get to know their elected officials better. “Of course,” he added, “we only put in there what we want to put in there.”

He’s no stranger to Web-based controversy, either. That happened last year, when he wrote posts voicing dissatisfaction with the local Republican Party, of which he was a member.

That act rankled some of the Republican rank and file, and Boger ended up apologizing to some of the party leadership with whom he had a personal relationship.

But it didn’t happen before he was a labeled a so-called Republican In Name Only, or RINO, on Facebook. He bristled at the name. Boger had just returned from Wisconsin, where he’d been knocking on doors for Gov. Scott Walker, who was facing fierce opposition from Democrats because of his attempt to revamp the state’s rules for collective bargaining among public employees.

When Boger logged onto his computer, he saw one woman in particular had branded him a RINO. He fought the urge to reply.

“I felt like saying, ‘I was doorbelling for Scott Walker. Where were you?'” Boger said. He thought better of it. “I didn’t want to toot my own horn.”

Social media pitfalls

Like many politicians, Vancouver Mayor Tim Leavitt (3,174 Facebook friends) exercises control over his Facebook feed. He locks it down to prevent people from posting disagreeable content.

He calls it “filtering out the nonsense.”

“I don’t tolerate name calling and vulgar language on there,” Leavitt said. “If I think people are getting heated, I’ll post a message saying, ‘Hey, let’s stay civil.'”

The immediacy of social media can lead to trouble. Look no further than Anthony Weiner, the former congressman and current candidate for mayor of New York City, who was twice caught gallivanting on social networks with women he met on Facebook and Twitter.

The first scandal broke because Weiner tried to send a racy “direct message” — Twitter-speak for a message accessible by only one recipient — to a young woman. Instead, he posted it to his public Twitter feed, viewable by his 50,000-plus followers. In the immediate wake of the scandal, he claimed his Twitter account had been hacked.

Other times, it’s controversial posts that get politicians into trouble.

At the local level, state Rep. Liz Pike, R-Camas, (1,463 Facebook friends) found herself paddling against the stream in July when she wrote a post in which she said teachers should be happy with their pay and implied they worked less than most people. She later apologized for her remarks, saying they showed a “little bit of ignorance on my part.”

For Camas Mayor Scott Higgins, a Facebook dabbler, “caution” is the most important word, as he sees a greater number of public officials directly addressing constituents.

He has a Facebook account but shies away from publishing posts that could be deemed politically divisive. Like he tells his kids –when you put something online, it’s forever.

More than anything, social media allows politicians to craft sound bites, Rabby said, because it enables them to create sanitized images that seem candid but aren’t.

The top political pitfall, he said, will be navigating a changing online landscape in which everything is viewed, stored and critiqued.

As for Guard, Washougal’s mayor, it boils down to staying connected with the broadest cross section of constituents he can.

“There’s no science to it whatsoever,” he said. “Out of 1,200 people on my Facebook, there are people from every walk of life.”

Tyler Graf: 360-735-4517; http://twitter.com/col_smallcities; tyler.graf@columbian.com.