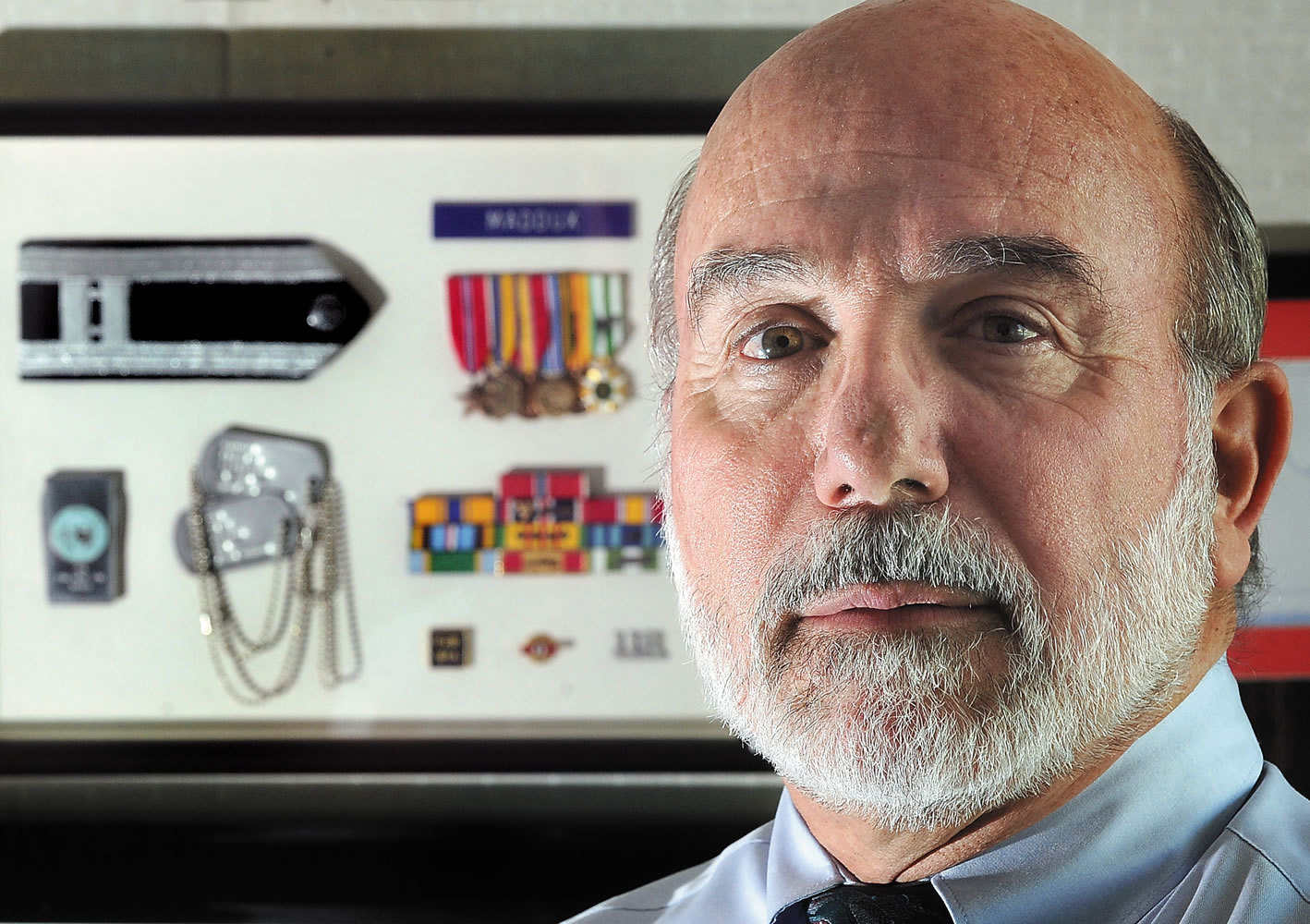

MEDFORD, Ore. — As a U.S. Air Force intelligence officer 40 years ago, Jim Maddux was a bit apprehensive when he first met the prisoner of war he was charged with debriefing.

“But when I walked into his hospital room, he said, ‘Hi, I’m Ron Bliss. I understand we’ve got some work to do,”‘ recalls Maddux, now 65, of Medford. “I told him, ‘Ron, we’ve got a lot of work to do.’

“He had memorized about 500 names and information about POWs in Vietnam — names, service, where last seen alive and the date,” he adds. “This was critical intelligence we needed.”

Maddux, now a senior financial adviser, was part of Operation Homecoming. Its mission: Return 591 prisoners of war from North Vietnam after the Paris Peace Accords were signed on Jan. 27, 1973. Most of the POWs had been captured in Vietnam, although a few came from Cambodia or Laos during the Vietnam War. They were being held in Hanoi.

The first group was released on Feb. 12, 1973. The operation continued into April that year. Bliss, a prisoner for seven years, was released March 4, 1973.

“We didn’t know what kind of shape they would be in,” says Maddux, a captain at the time. “We planned for the worst and hoped for the best.

“There had been reports that had come from sources in North Vietnam that there had been brainwashing,” he says. “We didn’t know if they would be robots. We didn’t know if they would be hostile to the United States. But it became readily apparent they were on very solid ground. There were a few cases of psychological issues, but 95 percent were pretty squared away.”

The longest-held civilian POW in Vietnam was Ernest C. Brace, now 81, of Klamath Falls. The former Marine Corps fighter pilot who flew more than 100 combat missions in Korea was flying for a civilian aircraft when it was shot down over Laos on May 21, 1965.

He escaped several times as a POW, but was recaptured and beaten severely each time. He was eventually sent to a POW camp known as the “Hanoi Hilton,” where he became friends with U.S. Sen. John McCain, R-Arizona. McCain was a Navy pilot who had been shot down in fall 1967.

Brace spent seven years and 10 months — 2,868 days — as a POW before climbing aboard the American plane at the Hanoi airport on March 28, 1973.

“My thoughts when I was getting on that plane in Hanoi (were) that I was going to have to find another job,” Brace said jokingly.

Actually, Brace, who still swims daily to keep in shape, spent several months convalescing before he could even think about work. Besides, he had some back pay coming.

“What I was thinking about was ice cream and pie, and steak and eggs,” he says.

Brace’s story is told in his 1988 book, “A Code to Keep.” In the foreword, written by McCain, the senator calls Brace a true American hero. The two old friends will see each other at a reunion of POWs at the Nixon Library in Southern California in May.

“We’ll see a bunch of the old POWs at the reunion,” Brace said.

Maddux, who had spent a year in Vietnam beginning in June 1970, and other intelligence officers involved in Operation Homecoming had learned everything they could about the POWs before their release.

“We utilized all our intelligence sources to maintain our POW/MIA index,” he says. “It was highly classified. We wanted to know their status.”

The son of Air Force Lt. Gen. Sam Maddux Jr., who retired in 1970, Jim Maddux would serve in the Air Force and the National Security Agency for nine years, working in intelligence all the while.

“Freeing these guys was on everyone’s mind,” he recalls. “As the air war intensified, we were losing a lot of crews.”

They were also concerned about the POWs’ physical, psychological and spiritual well-being, he says.

“And we wanted to get all the intelligence information these guys could shed light on,” he says, adding that information could literally save the lives of POWs still in captivity.

To re-educate the POWs, they prepared documents that brought them up to date with the news. Maddux and others working on the operation were at Clark Air Base in the Philippines. Preparations were made for their arrival at a large hospital on the base, he says.

Maddux was on the plane that landed in Hanoi on March 3, 1973. However, the restrictions permitted only a few select people on the ground. Maddux was not allowed off the plane during the hour and a half the plane was in Hanoi.

“They (POWs) came out of the buses and walked across the tarmac single file,” he says. “They had been given clean uniforms. It was very dramatic. They had all been cleaned up. The North Vietnamese had wanted to make a good impression.”

Maddux and the intelligence corps remained at the back of the plane during the flight back to the Philippines. Medical doctors and psychiatrists checked out the POWs.

“I didn’t talk to Ron Bliss on the plane — we didn’t want to start the process there,” Maddux says.

But Bliss, an F-105 pilot, was good to go once they returned to Clark Air Base.

“After we met, he asked if I had a tape recorder,” Maddux says. “He said we needed to go to a quiet room. That’s where he dumped the data.”

Bliss had been one of the POWs whom camp leaders had asked to keep the valuable information about prisoners in their heads.

“They compiled that information among themselves,” Maddux says. “That’s a real commentary on the leadership in the POW camps.”

Maddux kept in touch with Bliss for years afterwards. The former POW would become an international patent attorney. He later succumbed to cancer.