A tuft of teased hair was barely visible in the cubicle across from me. It was her, I realized, catching my breath. Helen Thomas.

It was 2009, and I was a 21-year-old intern for the Hearst Newspapers Washington bureau who had never been away from my home in Oklahoma for more than a week.

Helen was 88 and all that I wanted to be.

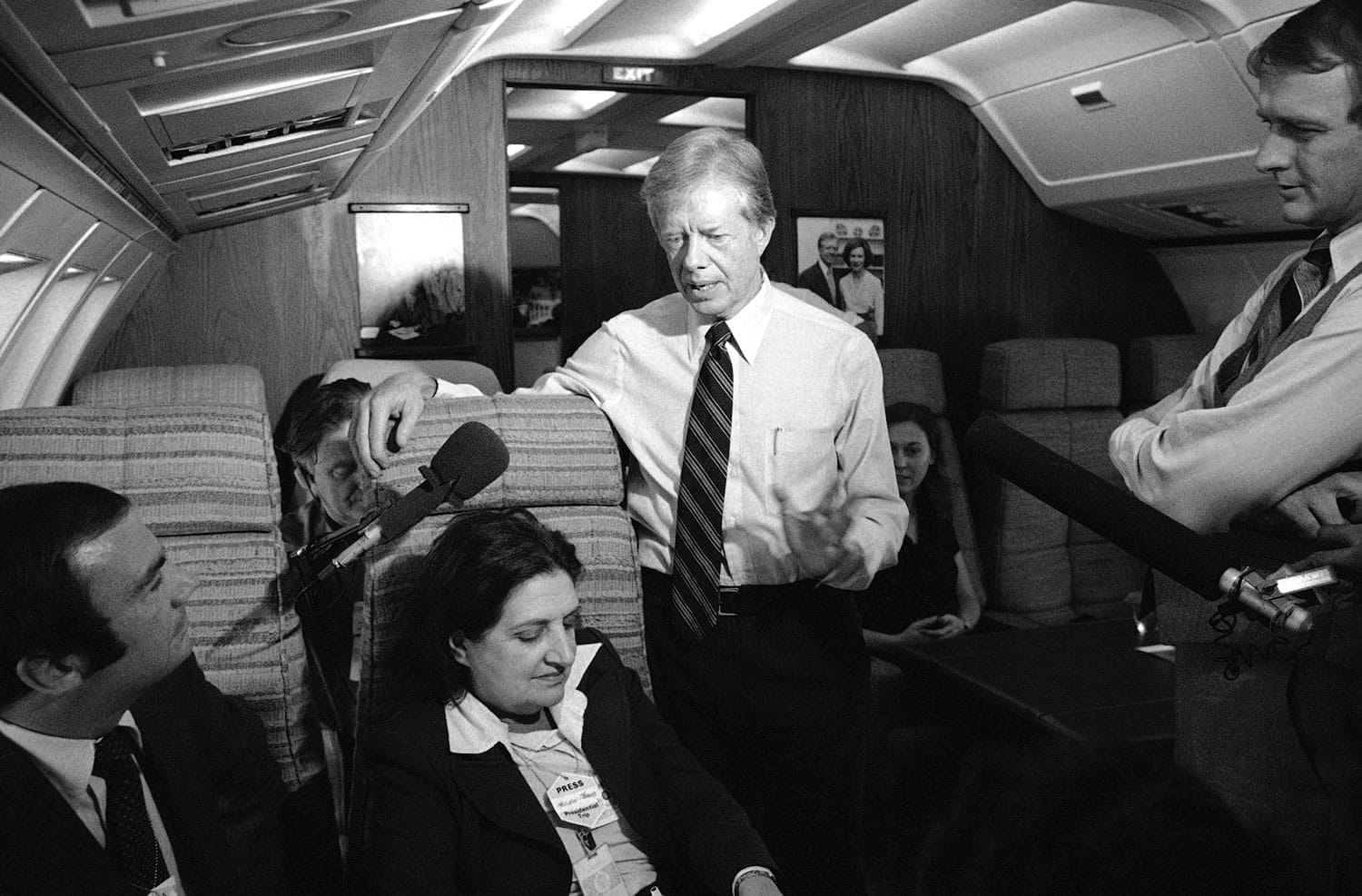

The columnist and former United Press International reporter had covered every president since John F. Kennedy. Now she was preparing to ask her first questions of President Obama, who had been inaugurated days earlier.

Sitting in my tiny rented room on Capitol Hill that evening, I ordered her autobiography, “Front Row at the White House.” She was gracious days later when, hands shaking, I asked her to sign it.

And she was gracious enough to be my friend for four years, a woman whose humility and generosity I won’t forget.

Helen died on July 20, a few weeks short of her 93rd birthday, at the apartment where she had lived for decades.

It was there that I last saw her in November. Framed photographs lined a small table in the living room. She was pictured with presidents.

Young female reporters owe much to Helen Thomas.

She battled the gender barriers that existed in American newsrooms, becoming the first woman to serve as White House bureau chief for a wire service. She also was the first female officer of the White House Correspondents’ Association, the National Press Club and Washington’s Gridiron Club.

Helen was about 22 when she came to Washington from Detroit to find a reporting job. She had told her mother that she was going to visit a cousin but, as the weeks grew into years, her mother’s, “When are you coming home?” became something they laughed about.

Helen asked tough questions of 10 presidents, and she was kind to young women trying to make it in the nation’s capital.

She was fragile when I met her — “rickety,” she called herself — and on many mornings I brought her coffee in her cubicle. She drank a lot of coffee, straight black, and was constantly refreshing her bright red lipstick.

It wasn’t long after I handed her my book to sign that she and I made dinner an almost weekly occasion. Often it was at Mama Ayesha’s, a Middle Eastern restaurant down the street from her home where “Helen’s table” was always saved.

There, over stuffed grape leaves, she shared stories about old reporters and about first lady Pat Nixon — who delightedly “scooped” Helen by announcing her 1971 engagement to Associated Press White House reporter Douglas Cornell. Nixon had stolen the microphone at Cornell’s retirement party and made public what Helen called a quiet romance.

Her memory was sharp, her stories fascinating. But at our dinners, Helen mostly asked about me. When people came to our table to shake her hand, she chuckled, almost shyly, and thanked them for stopping to say hello.

And no matter how late we stayed out, Helen always beat me to work.

During the day, I would help her down to her cab or escort her to the White House. When I held an umbrella over her head as we walked in the rain one afternoon, she laughed and said, “Thanks, Mom.”

Prior to one White House press conference, she saw that I had no place to sit and pointed to her chair in the briefing room. If she ever couldn’t make a press conference, she said, I could sit there.

I smiled but knew I couldn’t. It was in the front row, in the middle, the only chair with the name of an individual person, not a news outlet, inscribed on a plaque.

After I left Washington to finish journalism school and, later, to move to Los Angeles, we spoke on the phone every few weeks.

Helen always asked about my family and the stories I was working on. She joked that if I only would come back to the capital, “all would be forgiven.”

We spoke after she retired from Hearst in 2010, after anti-Israel comments she made after a White House event ignited a firestorm of criticism that continued after she apologized.

There was sadness in the voice of the woman whom I once had heard say that she planned to “die with her boots on” — a reporter till the end.

I often thumb through the first book I brought her to sign, the pages yellowed from the days I spent in sunny Washington parks, reading it as fast as I could so I could ask her about it.

On the cover page, in neat cursive, she had written: “Let’s hope for peace and prosperity in the 21st century.”

Eventually I bought all of her books and had her sign each one. In the last, she wrote what I think was her desire for all the young female reporters she met:

“I have great expectations of you and your career.Warmest regards,

Helen Thomas”

Hailey Branson-Potts is a writer for the Los Angeles Times. Email: hailey.branson@latimes.com.