SALEM, Ore. — They called them “lunatics” and “idiots” and, of course, in a famous book and Oscar-winning film both created right here in Oregon, people who lived in a “Cuckoo’s Nest.”

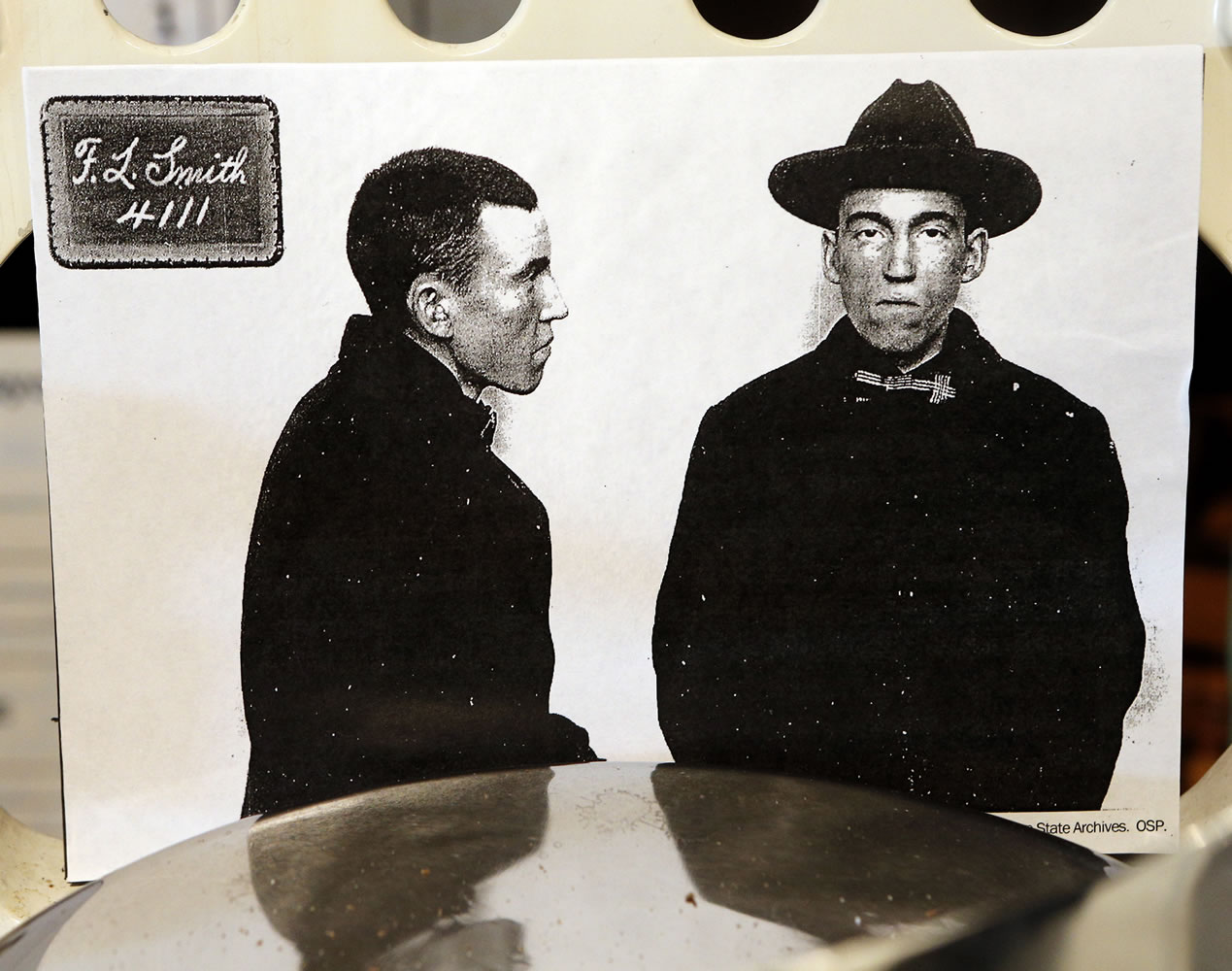

Now, visitors to the new Oregon State Hospital Museum of Mental Health can decide for themselves as they peruse the histories of some of the thousands of patients who walked through the hospital’s doors during its 130-year history.

Kathryn Dysart, a museum volunteer and one of 15 members on its board, hopes it will simultaneously educate the masses and help remove the stigma often attached to those who suffer from various illnesses of the mind.

“Our goal is to tell the story of the people who lived and worked in the hospital,” she said. “And, also, to raise the issues of mental illness. There is no one in the world who hasn’t been touched by mental illness or doesn’t know someone who has been touched by it.”

The museum opened Oct. 6, about six months after the new, state-of-the-art Oregon State Hospital was completed in an impressive remodeling project.

The museum is housed in the only part of the original hospital, which opened in 1883 as the Oregon State Insane Asylum, that remains.

Just north of the hospital is the Dome Building, where moviegoers first laid eyes on the handcuffed character of R.P. McMurphy — played by Jack Nicholson in the 1975 film “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” based on Ken Kesey’s 1962 novel of the same name — as he arrived at the hospital from prison for evaluation.

Not surprisingly, items related to “Cuckoo’s Nest” are prominent among the museum’s exhibits.

They include the leather director’s chair that says “Dean Brooks” on it, a gift from the film’s producers to the doctor who was the real hospital’s superintendent from 1955 to 1981, and who also played the fictional one in the movie despite having no previous acting experience.

Brooks agreed to allow filming at the hospital only after consulting with patients and staff, many of whom would be used as extras in the film, according to the eldest of his three daughters, Dennie Brooks.

‘Crazy folks’

When the hospital opened in October 1883, it was the state’s first public psychiatric institution. Three hundred seventy patients were transferred by train from the Hawthorne Asylum in Portland, a private mental institution.

A newspaper headline called it the “Exodus of the Insane,” with a subhead, “How the Strange Procession Appeared to an Outsider — Some of the Curious Conceits of Crazy Folks,” according to a museum display.

The hospital’s peak population was 3,545 patients in 1958, almost six times the 600 of today.

Until the 1950s, civil commitments, in which citizens could bring complaints about others and ask a judge to commit that person to public care after a doctor’s exam, along with family members committing loved ones, made up the majority of OSH’s population.

Children were also patients for decades.

Many of those patients, of course, lived tormented lives that are difficult to comprehend.

“2 a.m. Mrs. Bernard would not remain in bed. Restrained her with jacket and belt,” says an entry from the OSH Night Watch Book, Feb. 25, 1913, in a display case documenting cases related to “restraint and seclusion.”

A white straitjacket hangs in the case next to the words, “It is necessary to keep her hands in a straitjacket to prevent her from picking on her hands and head.”

Restraint and seclusion is still used within the walls of the gleaming new modern hospital, but only as a last resort, OSH spokeswoman Rebeka Gipson-King said during a tour.

She opened the Seclusion and Restraint Room in a hospital treatment mall that houses patients with dementia, brain injuries and other illnesses. Inside the room was a brand-new bed with belts attached.

“What we’re working toward is not having these rooms at all,” she said.