NEW YORK — Two doses of Merck & Co.’s human papillomavirus vaccine may be just as effective in younger girls as the recommended three doses given to older teens and women to help protect them against the virus that causes cervical cancer, a Canadian study found.

Girls ages 9 to 13 years who received two doses of Gardasil had antibody levels that were not worse than females ages 16 to 26 years who received three doses, according to research published Tuesday in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

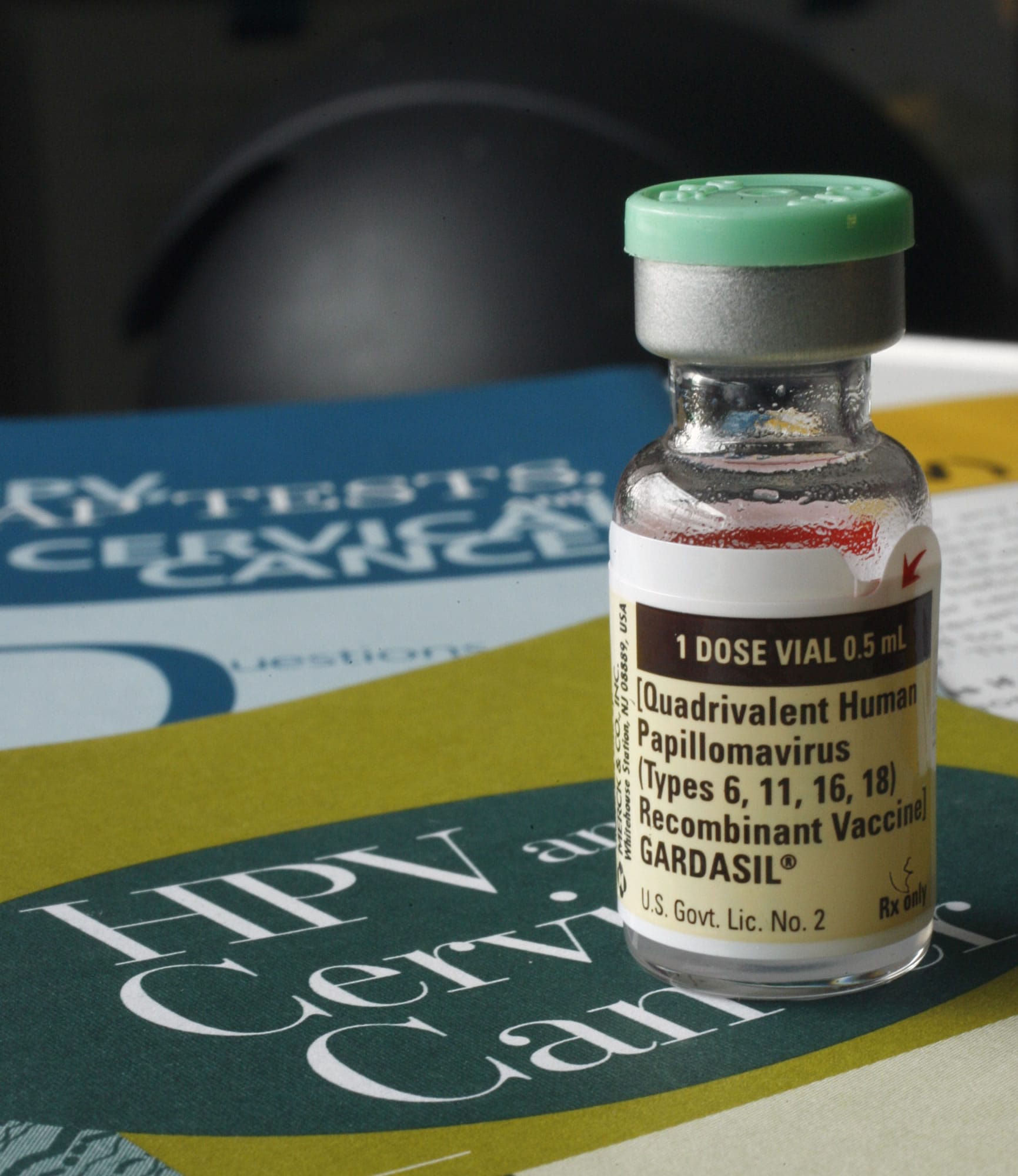

The study is the first to look at the effects of reducing the doses of Gardasil, which protects against four strains of HPV, the virus that causes genital warts and cervical cancer, to see if the vaccine is still effective, the authors wrote. More studies are needed before the recommendations for vaccine doses should be changed, said Simon Dobson, the lead study author.

“The public health question is, is there enough information in this study to say that a two-dose schedule for young girls is all right. The answer is not quite yet,” Dobson, a clinical associate professor in pediatric infectious diseases at BC Children’s Hospital at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, said in a telephone interview.

The project was funded by ministries of health in British Columbia, Nova Scotia and Quebec. Merck Laboratories did antibody tests at no cost.

Studies are needed to look at how long girls who receive two doses of the vaccine maintain their immunity to the virus and whether a third booster shot might be needed as they get older, Dobson said. Research is also needed to determine whether two doses given to 9- to 13-year-olds works as well as three doses in preventing HPV infections.

HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection and is the main cause of cervical cancer, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About 12,000 U.S. women get cervical cancer each year. In order to prevent cervical cancer in adults, the HPV vaccine needs to be given before a person becomes sexually active. In the United States, the CDC recommends vaccination with Gardasil for girls and boys ages 11 and 12, but it is also approved for those ages 13 to 26.

Gardasil generated more than $1.6 billion in 2012 sales for Whitehouse Station, N.J.-based Merck, the company reported in a regulatory filing. Cervarix, a HPV vaccine from London- based GlaxoSmithKline, had about $428 million in 2012 sales, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

Researchers in the study looked at 830 females in Canada. Girls ages 9 to 13 received either three doses of Gardasil or two doses of the vaccine, while young women ages 16 to 26 years received three doses of the vaccine. The blood antibody levels to HPV were then analyzed.

The study showed the antibody levels to HPV after three years in girls who received two doses of the vaccine were no worse than those of young women given three doses. The research also found that the antibody levels differed over time between the girls ages 9 to 13 who were given two doses versus three doses.

Dobson said more research is needed to better understand those findings. Those results might not be negative because it could be that the body doesn’t need much antibody to be protected against the virus.

Jessica Kahn, who wrote an accompanying editorial in the journal, said reducing the number of shots from three to two may help make it easier for kids to get the correct number of doses. Many girls and boys don’t return to get all three shots. Two doses of the vaccine may also make it more affordable, particularly for developing countries, she said.

“It’s an important study and it shows encouraging evidence, it’s preliminary evidence, that a two-dose vaccine series possibly could be effective in the future,” said Kahn, a professor of pediatrics at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center in Ohio, in an April 29 telephone interview. “It’s a little too early to change clinical practice based on these findings. It’s one piece of the puzzle.”