eople throughout history have come up with some strange ideas about the origins of cancer, but even today we don’t know for sure why it makes some cells behave badly.

That’s not to say that scientists and doctors don’t know a lot about the illness. They know many risk factors that can lead to specific cancers. They understand the pathways the disease takes through the body. And the medical community has made great strides in treatment that have led to a 98 percent survival rate when breast cancer is caught in the early stages.

But they still don’t know exactly what causes the disease.

“We don’t completely understand why it happens, but (what happens is a cancerous) cell gets stuck in its cycle and starts to reproduce,” said Dr. Toni Storm-Dickerson, a breast surgical oncologist at Compass Oncology.

Cancer starts with a single malformed and malfunctioning cell that replicates itself every 40 days or so. From there the cancer grows exponentially as the two cells replicate into four, the four into eight, and so on.

“It takes about 1 billion cells to be able to feel something (with your hand),” Storm-Dickerson said. “But imaging can pick things up before that, which is why imaging is so important. Imaging saves lives.”

In ancient Egypt, Greece and Rome, physicians could diagnose breast cancer only when visible tumors started to appear.

The Egyptians, like many cultures at that time, blamed it on the gods.

The Greek physician Hippocrates thought that health was related to the balance of four body fluids: blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile. And since tumors were often black, he thought they were related to an imbalance in black bile.

That theory remained pretty much the global standard from 400 B.C. up until the early 1700s, when a new idea took hold that cancer came from fermenting and degenerating lymph in the body. Lymph is a colorless liquid that circulates and redistributes white blood cells, protein and excess interstitial fluid through the body.

In the 1700s, physicians believed life was associated with the movement of fluids through the body, mainly lymph and blood. The thought was that tumors grew in lymph and were then thrown out into the blood to populate the body.

In the mid-1800s, doctors proved that cancer is made of cells, not lymph, but they believed the cells originated on their own and didn’t come from malfunctions in normal cells. In the late 1800s, German pathologist Rudolph Virchow proved that all cells, including cancer, come from other cells.

Other ideas passed down through the ages were that physical trauma caused cancer, that cancer was contagious or that cancer was caused by repeated skin irritation.

We may still not know exactly what causes cells to deform, but the medical community has a much more evolved understanding of the risks than ever before.

“The thinking is that as our cells age, when they try to replicate themselves, mistakes happen,” said Joan Wendel, breast cancer nurse navigator at The Vancouver Clinic. “They think that might be why we see more cancer in older people. But it can also be caused by things in the environment, and we’re not sure what elements impact what.”

The biggest risk factor for breast cancer is being female. And if that sounds redundant, it’s not. About 1 percent of the cases occur in men.

The second-biggest risk factor is age. About one out of eight invasive breast cancers are found in women younger than 45, while two of three invasive breast cancers are in women age 55 or older, according to the American Cancer Society.

Genetics can also play a role.

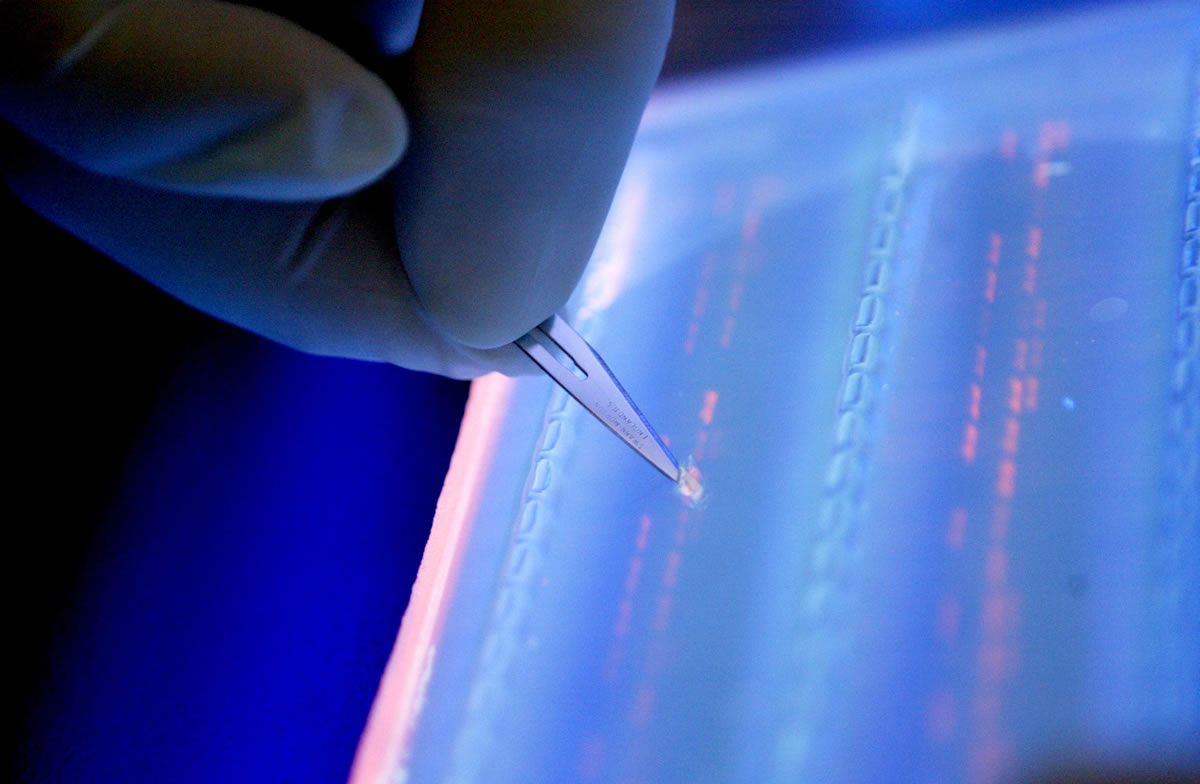

Mutations in two genes, BRCA1 and BRCA2, which help prevent cancer by making proteins that stop abnormal cell growth, can be passed from parent to child and can increase the risk of cancer.

Other defective genes can also create a higher cancer risk, but they are more rare.

A family history of breast cancer, especially if a close relative such as a mother, sister or daughter has had the disease, makes a person three times more likely to get it.

And women who start menstruating early (before age 12) and/or go through menopause late (after age 55) have a slightly higher risk of breast cancer, possibly because of longer exposure to the hormones estrogen and progesterone.

Risks of cancer also increase through exposure to radioactivity, environmental contaminants, viruses and other factors.

Cancers that begin in the breast can also transform into cancers in other parts of the body.

Cancers are named after whatever organ they started in. So breast cancer cells could spread and start cancer in other areas, but the disease would still be called breast cancer.

“The only thing that cancers share across the board is this ability to move to other areas and go deadly,” Storm-Dickerson said. “It’s evil and nasty.”

Cancer cells can travel through the blood stream and through the lymph. Doctors can use chemotherapy and radiotherapy to fight the disease in blood, but it’s much harder to stop in the lymph system, Wendel said.

“The lymph system is so complex that we just don’t have the ability to (stop cells traveling through it), and I’m not sure we ever will,” Wendel said.

Still, technological developments, genetic mapping, complex chemistry and other breakthroughs have greatly improved both the understanding and outcomes of the disease today.

“Treatment has evolved phenomenally in the last 20 years,” Wendel said. “It’s amazing the strides that have been made. Methods are now tailored to the biology and the individual. It’s very customized, and the outcomes are getting better and better.”

The Internet and connections between the global community of oncologists has also greatly improved patient outcomes. Doctors can now work on issues in a network together and track the success of various techniques on groups of patients.

“Now we look at ourselves globally,” Storm-Dickerson said. “Experts can compare outcomes to (those of) the best surgeons in the world.”

And even if some cancers can’t be cured, the multifaceted approach to today’s treatments means patient outcomes are greatly improved, Storm-Dickerson said.

“We know we can always help,” Storm-Dickerson said. “Most of the time we win, and even if we don’t, we can still help. We can give them that next Christmas, that next birthday with their kids.”