BEIJING — Six decades after Y.T. Wu founded an organization used by the Communist Party to control churches in China, his son is suing the government to get Wu’s diaries back in hopes of rehabilitating his image among the many Chinese Christians who despise him.

To this day, the vast rift caused by Wu’s organization defines China’s churches. Among the booming unregistered churches, he is vilified. Some worshippers call him a Judas who delivered China’s Christian community into the hands of the Communist government and abetted the persecution of hundreds of thousands of Christians.

Yet in government-sanctioned congregations, Wu is revered for creating the Three-Self Patriotic Movement in charge of all Protestant churches.

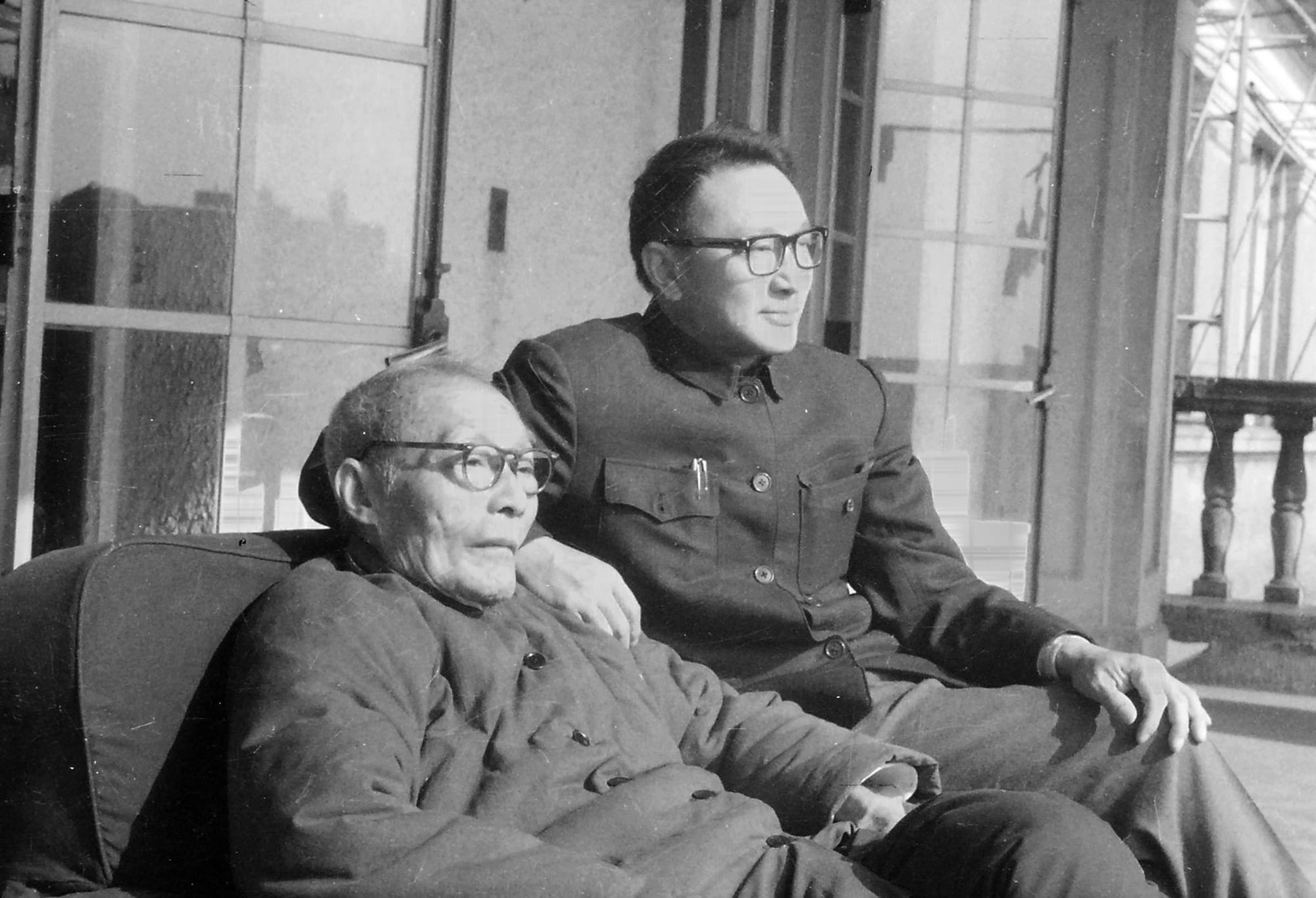

Since Wu’s death in 1979, these dueling legacies have haunted his son, Wu Zongsu. Now 84 and in the twilight of his own life, the son is spending his final years and a small fortune trying to piece together a more nuanced portrait of his father.

The key to that, however, lies in a 40-volume collection of diaries that the younger Wu says he lent to the Communist Party days after his father’s death and has been unable to recover.

Wu believes that if church scholars could access his father’s early writings, they would understand his original vision for China’s churches — a vision he says the Communist Party later twisted to suit its own purposes.

In a phone interview from San Francisco, where he now lives, Wu called the lawsuit against China’s government a last-ditch effort that has slim chances of succeeding.

“I don’t have much time left, and there is no one after me to do this work,” he said. He is the last remaining heir and has no descendants of his own. “Some call my father a prophet; others say a betrayer. But the truth is he was just a man, a very complicated one.”

Wu was in his 20s when his father began the Three-Self Patriotic Association in the 1950s. China’s Communist leaders had finally won control of the country, expelled all foreign missionaries and set up an atheistic government.

At the private urging of China’s premier, Zhou Enlai, and after meetings with Party Chairman Mao Zedong, Y.T. Wu — also known in China by his full name, Wu Yaozong — spearheaded the establishment of a national church that would be free from foreign influence and completely loyal to the new Communist government.

The resulting organization took its “Three-Self” name from its principles of self-governance, self-support and self-propagation of the Gospel.

Bitter rift

Congregations that submitted to the organization’s authority were allowed to carry on; those that did not were declared enemies of the state. In the ensuing years, thousands of people were arrested and imprisoned, according to church historians, as Christian worshippers, churches and pastors were encouraged to inform on each other.

With the late-1960s Cultural Revolution, registration became moot. All religion in China was banned, and even previously state-backed church leaders were sent to labor camps, Y.T. Wu among them.

But from that repression emerged a thriving illegal underground church movement, whose growth outpaced that of the government’s Three-Self churches when they were restored in 1979.

A bitter rift between China’s official and illegal churches has existed ever since.

A government think tank in 2010 pegged the number of Chinese Protestants at 23 million, but outside experts estimate an additional 35 million belong to the enormous underground churches.

To this day, many in the underground churches as well as overseas Chinese Christians question the motives of Wu’s father for creating a state church and ask whether he even believed in God.

Wu argues that while his father was flawed, he was an idealist who subscribed to the mistaken belief that Christianity could coexist with the Communist government, rather than be controlled by it.

During the Communist revolution, Wu notes, party leaders spoke of many of the same ideals as Christians — equality, people’s rights and values. “My father saw Communism and Christianity as two sides of the same truth — in pursuit of the same goal, a better society.”

The son said he became disillusioned with Communism in 1989, when Chinese troops opened fire on Tiananmen Square activists. He was teaching at the time at a university in San Francisco and decided to remain there.

“I realized then that Christianity and Communism are like fire and water,” he said. “Christianity emphasizes love. Communism emphasizes the life and death struggle of classes.”