For my next trick, I’m going to urge all of you to watch a new reality show that’s set in Alaska.

Wait, come back! I get it — the last thing in the world you’re likely to watch is one more reality show set in Alaska, since we already have about a hundred to choose from.

So hear me out as I describe the exquisite and sometimes melancholy effect of watching Animal Planet’s “The Last Alaskans,” a superb, eight-part docuseries that premiered this week. Without overblown narration or any of the other heavily produced tropes and techniques that viewers associate with the genre, “The Last Alaskans” quietly settles in with some of the last legal residents of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

What happens next? Not a whole lot, except for a patient rumination on the themes of independence and solitude in nature, minus the posturing and usual yammering about the Second Amendment, snow machines, gold fever, etc.

A congressional act in 1980 banned further human occupation in the refuge, which is hundreds of miles from the nearest city and covers a vast and pristine chunk of the state’s northeast corner. According to the show’s intro, only seven cabin permits remain under a grandfather clause, entitling the occupants and their immediate descendants to continue living on the refuge.

“The Last Alaskans” embeds with four of these stalwart households, the members of which tend to arrive at the end of the summer (as floods and mosquitoes subside) and set about hunting for the red meat and fish that will sustain them through a bitterly cold winter that includes two months with hardly any sunlight.

Produced by Bethesda, Md.-based Half Yard Productions (whose other works include TLC’s “Say Yes to the Dress”), “The Last Alaskans” was filmed with minimal crew and an evident respect for its setting and subjects, who simply aren’t the sort of people who wait around hoping to get on TV.

Sport cameras attached to drones provide the viewer with an almost foreboding sense of how large and remote the refuge is — and how isolated the cabins are from each other, separated by more than 100 miles. Unlike other reality shows, there’s little sense that a producer is nudging a particular narrative this way or that; the subjects are entirely themselves and, given their loner instincts, remarkably willing to explain why they live here and how they manage it.

“It’s easy to die up here,” says Bob Harte. “Everything else is work.”

Harte, who is in his 60s, taught himself to fly what might be the most ramshackle single-engine airplane in the state, which gets him to and from Fairbanks for occasional supply runs. He’s the talkative heart and soul of “The Last Alaskans” and seems genuinely pleased to have the company.

The more you learn about Harte, the more you admire him — and also worry for him. Cameras or not, he’s a tad danger-prone (a plane crash here; a stalled boat motor in swift current there; a bear raid on his cabin in his absence) and he says he’d be perfectly happy to meet his end in these woods. He’s still nursing the hurt of a long-ago divorce and misses the daughter who was born in his cabin and yet shows no apparent interest in visiting anymore. One windy afternoon, Harte climbs a very tall tree to adjust an antenna that picks up a faraway radio station where callers leave messages to those living far off the grid. One night his ears perk up when his ex-wife leaves a greeting. It’s the only communication he has, and it’s decidedly one-way.

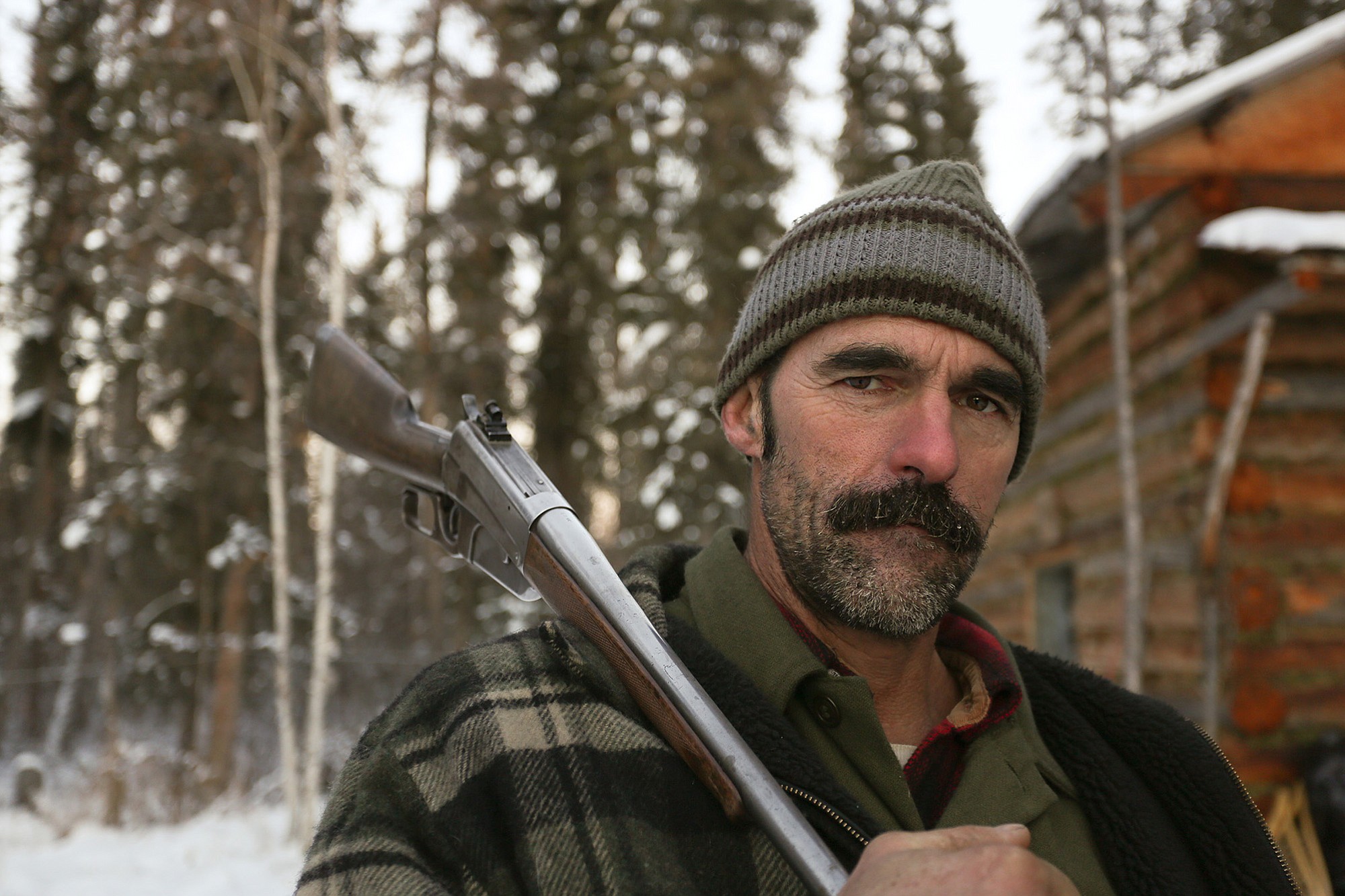

Elsewhere, Ray Lewis arrives with his wife, Cindy, and their three daughters for the fall and winter. The Lewis family spends summer in Fairbanks, which Ray describes as a marital compromise — while Cindy gets her city fix (and the family earns money) Ray itches to return. Now their daughters are getting old enough to move away and perhaps lose interest in sustaining the family’s claim on the cabin.

Bearing a striking resemblance to Daniel Day-Lewis in “There Will Be Blood,” Ray may have no idea how suited he is to TV or how elegant his deepest thoughts about nature and quietude must sound to those of us sitting on sofas shoveling low-fat yogurt into our maws.

Like everyone else on the show, he’s mostly just fixated on killing an animal big enough to provide the winter’s meals.

Speaking of meat, this is the first time in a long time I’ve felt any emotional investment while watching people hunt and fish on TV. In that regard, “The Last Alaskans” is in many ways an ideal program for a channel that stills calls itself Animal Planet. Even though it’s about people, they are inextricably linked to not only their pet dogs but the wildlife all around them.