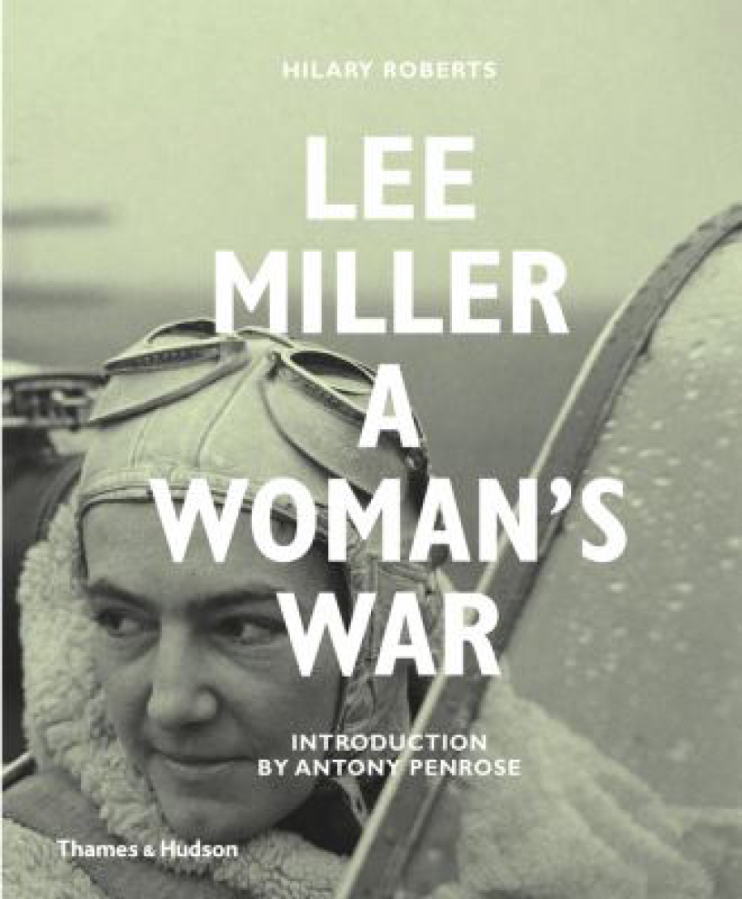

One of the great joys of my job is the ability to have chance encounters with a variety of books. Just such an encounter is what prompted me to pick up this week’s title, “Lee Miller: A Woman’s War.” Scanning the carts of new books making their way through our cataloging and processing department, my attention was drawn to today’s book cover: a black and white photograph of a female pilot. I have always been interested in the art of black and white photography, but I haven’t spent much time getting to know the photographers themselves beyond, say, Ansel Adams and Margaret Bourke-White. Lee Miller was unknown to me, but now having read Hilary Roberts’ in-depth look at Miller and her wartime photography, I am glad to have spotted this recent addition to the library’s collection.

Highlighting Miller’s photographic work during World War II, author Hilary Roberts has gathered together an impressive collection of Miller’s images taken while she was first a studio assistant for British Vogue and then later as one of just “four American female photojournalists accredited as official war correspondents to the U.S. armed forces.” In the book’s introduction, written by Lee Miller’s son, Antony Penrose, we learn that Lee had a short-lived career as a model, photographed regularly by Edward Steichen, the chief photographer at Cond? Nast at the time he met Miller. Around this same time she met another famous photographer, Man Ray, who would have an unmistakable influence on Miller’s transformation from photographer’s subject to respected photojournalist.

The book begins with a selection of Miller’s pre-war photographs which tend to display a decidedly surrealistic bent — not surprising since she was in close company with Man Ray, a significant contributor to the Surrealist movement. These early photographs focus primarily on women — especially friends and acquaintances who were either artists or muses — sometimes both — during Surrealism’s zenith in the mid-1920s and early 1930s.

Chapters two and three feature Miller’s work during her days as a photographer at British Vogue, then as a war correspondent in Great Britain from 1939-1945. Her fashion photography is much as you would expect from a high fashion magazine like Vogue, but even here her admiration of the Surrealist culture is evident, especially when she chooses to frame her subjects at an air-raid shelter or among the rubble of war-torn London.