As a water hose began filling a gigantic pressure vessel in the welding and fabrication lab at Clark College, this was the moment of truth.

Wielding small flashlights, the 11 students who had spent 700 hours building the vessel inspected their handiwork for leaks. Would the tank hold water? How many leaks would it spring?

Winter quarter was the first time Clark’s welding program had offered the advanced process class requiring such a complex project. The class — and the entire program — was redesigned by Caleb White, who heads Clark’s welding and fabrication technology department and also teaches the class.

Formerly, the program focused on welding. Now, students still weld extensively, but they also learn fabrication. That includes layout, reading blueprints and more, White said. The revamped program prepares students for real-world jobs.

Welding employment outlook for Southwest Washington

• 780 welders employed in Southwest Washington.

• Key industries: metal fabrication, 270; other manufacturing, 230 and construction, 100.

• Median wage: $22.18 per hour or $46,134 annually.

Source: Scott Bailey, Southwest Washington regional economist, Washington State Employment Security Department

White added new equipment including a press brake and computer numerically controlled plasma-cutting machine, which can create any shape designed on a computer-aided engineering program. He noted the equipment is standard in fabrication shops.

“The best way to survive in the industry today is to be well-rounded,” White said. “I survived the last economic crisis by being versatile. That’s what I’m telling these students.”

Previously, he worked at luxury yacht builder Christensen Shipyards for a decade. His diverse work in the metal shop and mechanical department included everything from building elevators to installing engines.

“The reason I survived is because I could be shifted from department to department as needed,” White said.

He left his job at Christensen when he was offered the teaching job at Clark College.

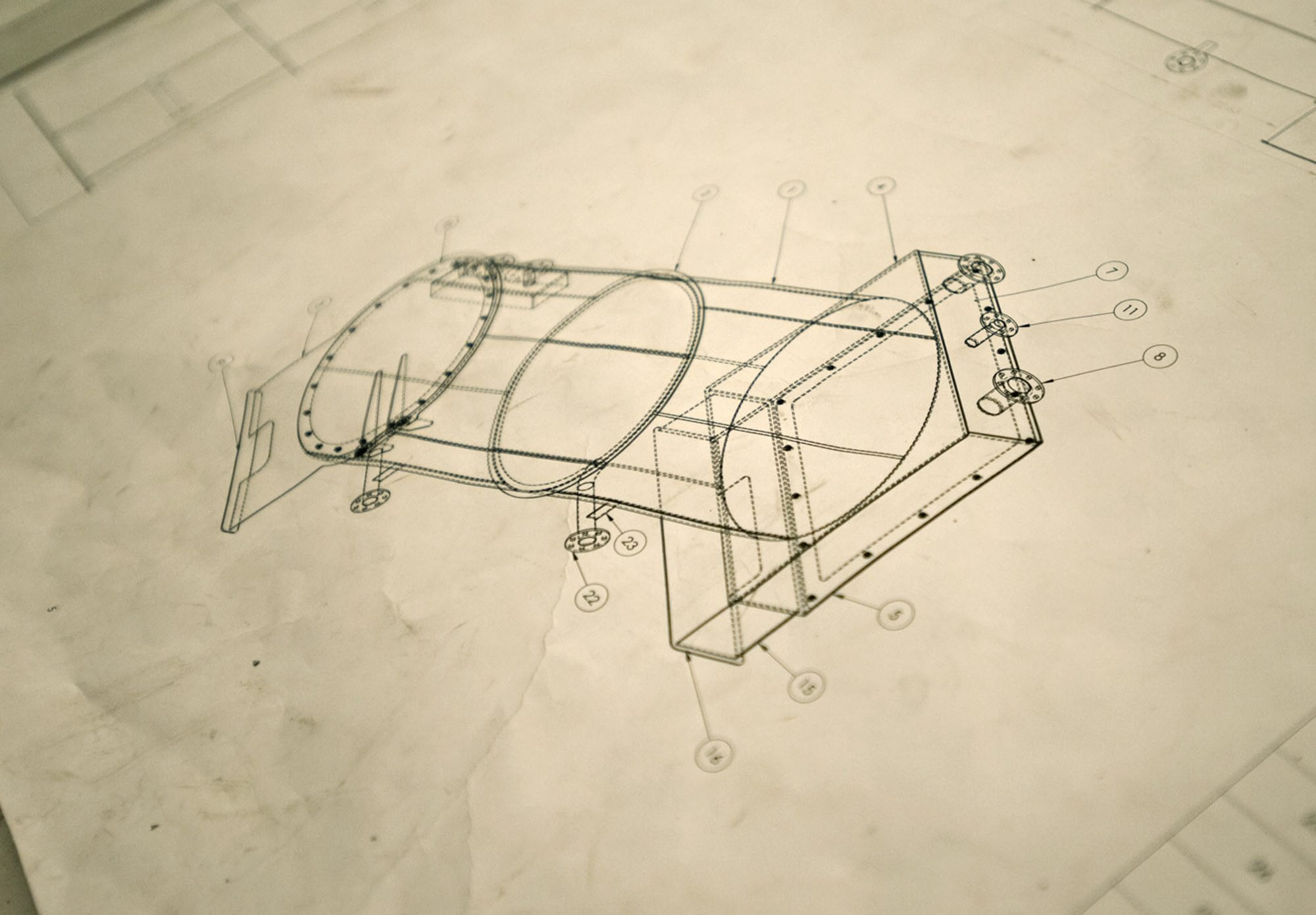

White designed the pressure vessel in SolidWorks, a brand of solid-modeling, computer-aided design and computer-aided engineering software. Next, he made a blueprint. During the first week of class, he led students in a design review process.

“Then I asked them, ‘What’s it going to take to build something like this?’ ”

The first assignment was for students to determine a quote for the job of fabricating the pressure vessel: material cost, labor cost, hours and any special jigs or fixtures required to complete the job.

Their next assignment was to build the pressure vessel. When empty, the 715-gallon tank weighs 1,100 pounds. Filled with water, it weighs 7,000 pounds. To test the vessel, White did a hydro-pressure test rather than an air-pressure test.

“It’s a good teaching point to show how water will add its own pressure to the vessel,” White said. “Water testing is much safer. Air testing is faster, but you have to be cautious with it. You could blow the doors off. You could ‘oil can’ it.”

That’s when the air pressure blows the shape out and renders the vessel unusable, he explained.

A slight-but-steady stream of water leaked from under the tank. A student used a bucket to catch the water. As the tank filled and more leaks were detected, students used chunks of soapstone to mark the position of leaks and keep a leak tally on the tank’s side.

“Where’s our water level?” asked White.

Student Jared Kench climbed a ladder, shined a penlight into the flange at the top of the tank and fed a steel measuring tape inside.

“Thirty-nine inches,” he replied.

Kench, 34, of Washougal had been working in the health care field — “kitchen, maintenance, landscape — anything not medical. But I couldn’t make any more money. I needed to switch careers. I have a family. A mortgage.”

As the students have learned fabricating and welding skills, they also have reinvented themselves and have improved their prospects for better jobs, brighter futures. By the time the students graduate from the two-year program in the spring, they will be ready to work in the field. Some students accepted jobs before completing the program.

Pacino Palmore, 32, worked as a steel fabricator, brake press operator and crane operator before he was laid off.

“I got an opportunity to come back to school. I wanted to educate myself more about metal,” Palmore said. “Before, I happened to get a job. Now, I can pick a career in the welding industry.”

Just two years ago, Peter Smith graduated with his high school diploma through Clark’s adult high school diploma program. He immediately entered the welding program. Now Smith, 50, works full time as a fabricator at Columbia Machine and attends Clark full time.

“I didn’t even know how to weld when I first came here,” he said, using a chunk of soapstone to write “5” on the side of the vessel, signifying that a fifth leak had sprung.

“Most welding programs teach you to weld, but they don’t do anything like this,” Smith said, gesturing toward the enormous pressure vessel.

The only woman in the class, Melissa Harvey, 38, was a homemaker who decided to find a new career when her kids were teens. She chose the welding program, in part, because of its permanence and job security. Another reason she chose welding was the influence of her father, a lifelong construction worker. She said her dad supports her career choice. Every day, she sends him photos of her work in the shop.

“I bring my projects home and set them on the table,” Harvey said. “He looks at them for hours. He’s fascinated.

“I love being in the shop. This is my element. There should be more women here. There’s not many women in the trades.”

After David Jeffers was laid off from his work as a grinder and finish worker in the steel industry, his research found welding jobs to be plentiful. He said he’d always wanted to learn to weld.

Jeffers held a penlight to the tank door as he peered at the silicon seals and discovered they were leaking. Students had opted for silicon rather than more expensive rubber gaskets, but they did the work only a day before the test.

Job outlook

White, the instructor, listed many applications for pressure vessels: nuclear applications, boilers to heat buildings, distilleries, steam engines and oil refineries. Each application has certain codes they must follow. The majority of pressure vessels are governed by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers.

All pressure vessels must be pressure-tested before they are allowed to be used, White said. First, they are pressure-tested with air and checked for leaks with a soapy water solution that will bubble if a leak is present. Next, vessels are hydro-tested with water, as the Clark students had done. Hydro-testing is always done last because if a leak is found, all the water — sometimes thousands of gallons — has to be drained.

Clark’s welding and fabrication technology program provides students with required welding and fabricator skills to be competitive in the workplace. Students who complete the program should be able to read blueprints, analyze parts to be jointed, and carry out proper fitting, welding and inspection. They work with a variety of materials, including steel, stainless steel, aluminum, titanium, copper or bronze.

Official employment projections show the need for about 40 additional welders a year in Southwest Washington to keep up with growth and retirement, said Scott Bailey, Southwest Washington regional economist with the Employment Security Department.

“But we’re growing about twice as fast as projected, so it may be closer to 60,” Bailey said. “The other thing I hear a lot is that welding is a skill needed in a lot of related occupations, so regardless of the demand for welders, there is a demand for workers with welding skills.”

If this were a working shop and the pressure vessel were going to a customer, White said, they would drain it and fix the leaks. He is not sure what will become of the student-built pressure vessel, but he is considering selling it and putting the proceeds back into the department to help pay for the spring quarter project, a 14-foot aluminum boat. Some students suggested the tank would make an excellent, enormous barbecue grill.

White said Clark College has about $1,000 invested in the pressure vessel, but the cost was reduced thanks to materials donated by Columbia Machine and Farwest Steel. Marks Brothers in Boring, Ore., provided vessel-testing expertise.

As the test wound down, students had detected five leaks in the welding.

“I’m really pleased,” White said. “I’ve seen professional fabricators with more leaks. I’m really proud of those guys.”