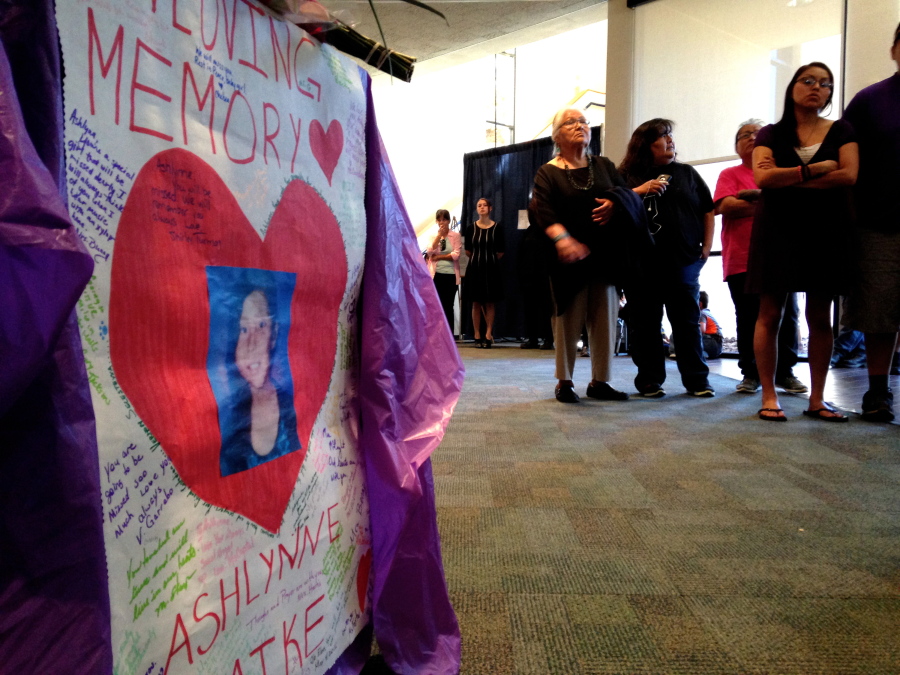

FARMINGTON, New Mexico — Thousands of people from across the Navajo Nation came together Friday to share their grief at the funeral of an 11-year-old girl who was lured to her death by a beckoning stranger.

Ashlynne Mike was killed after the man allegedly persuaded her and her 9-year-old brother, who had been playing near their bus stop after school, to climb into his van. The boy said the man took them deep into the desert, and then walked off with his sister to an even more remote spot, before coming back to the van alone.

An FBI agent’s affidavit says Tom Begaye Jr., a 27-year-old Navajo from a community just down the highway from the children’s home, told investigators he assaulted the girl and struck her twice in the head with a crowbar.

The Farmington civic center was packed with more than 1,600 people, and just as many stood outside. Entire families came to mourn her, hugging each other and their children. Many wore yellow T-shirts — one of her favorite colors.

New Mexico Gov. Susana Martinez recalled Ashlynne as a budding musician who wanted to share her talents in playing the xylophone and piano with others. She called on the crowd to carry on the kindness Ashlynne showed the world.

“I cannot imagine the pain Ashlynne’s loved ones feel right now,” the governor said. “But even as we mourn her, we should celebrate her life and remember what a beautiful little girl she was, inside and out.”

More than 200 miles away in Albuquerque, Begaye appeared in U.S. District Court, waiving his right to a preliminary hearing on murder and kidnapping charges. The federal judge ordered that he remain in custody.

The slaying has raised tough questions for both the community and law enforcers on the country’s largest American Indian reservation, which stretches for 27,000 square miles into New Mexico, Utah and Arizona.

Begaye told investigators that the girl was still moving when he left her, according to the affidavit. But eight hours passed between the family’s initial missing persons report and the Amber Alert, which went out at 2:30 a.m. Tuesday.

Her body wasn’t found until later that morning, south of the Shiprock Pinnacle, just inside the border of the Navajo Nation in the northwest corner of New Mexico.

The alert set off cellphone alarms that jolted New Mexico residents awake and provided the first warning beyond the Navajo Nation to keep watch for Ashlynne and the suspect.

Some believe more could have been done to find the girl alive; others say issuing the alert would have made little difference. All seem to agree that precious time was wasted while authorities evaluated and belatedly shared what information they had.

“My phone buzzed and I realized that this has gotten really serious. Why did it take so long for the Navajo Nation to issue an Amber Alert?” said Rick Nez, president of the tribe’s San Juan Chapter, where Ashlynne lived.

The Navajo Nation, which counts 300,000 members, does not have a system to issue its own child abduction alerts. Across the U.S., only a fraction of the 566 federally recognized tribes do. In most cases, state authorities coordinate with the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children to spread the word about abducted children in danger of serious injury or death.

The Navajo were one of 10 tribes named in a 2007 pilot project through the U.S. Justice Department to expand Amber Alerts into Indian Country, but it did not materialize.

Heidi Jose, a relative of Ashlynne’s, said she has long felt Navajo police are slow to react to reports of missing people and requests for help from residents. She and dozens of others questioned the delay in the time that police learned the girl was missing and when surrounding agencies got word to provide re-enforcement.

“Why is it that they’re not snapping their fingers, you know, and saying, ‘A child is missing. OK, let’s go,’?” Jose said. “This is something that for them — the Navajo police — is a wake-up call.”

Navajo police Capt. Bobby Etsitty says the delay stemmed from a lack of information on the abduction and the suspect and from the time it took to notify outside authorities.

The FBI handles major crimes in Indian Country when the suspect, victim or both are American Indian.

By 8:30 Monday night, the FBI was aware of the kidnapping, according to Framingham Police Lt. Taft Tracy, and yet the agency didn’t notify the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children of the need for an Amber Alert until nearly four hours later, at 12:20 a.m. Tuesday, the center’s Robert Lowery Jr. said.

FBI representatives have declined to answer questions from The Associated Press seeking to clarify the agency’s response.

Two more hours passed while the New Mexico State Police evaluated the center’s request before the alert went out.

Meanwhile, the local sheriff’s office said it found out about the kidnapping by chance, around 9:30 p.m. when talking to FBI about an unrelated case.

“We struggle sometimes with communications between agencies and especially with the Navajo Nation,” San Juan County Sheriff Ken Christensen said. “We’ll expend all resources when it comes to a child. We want to get that kid back alive.”

Tribal lawmakers are seeking explanations for the delay.

Navajo President Russell Begaye, no relation to the suspect, acknowledged this week that the tribe needs a more effective response system using modern technology.