We knew this was coming.

For months, coral reef experts have been loudly, and sometimes mournfully, announcing that much of the treasured Great Barrier Reef has been hit by “severe” coral bleaching, thanks to abnormally warm ocean waters.

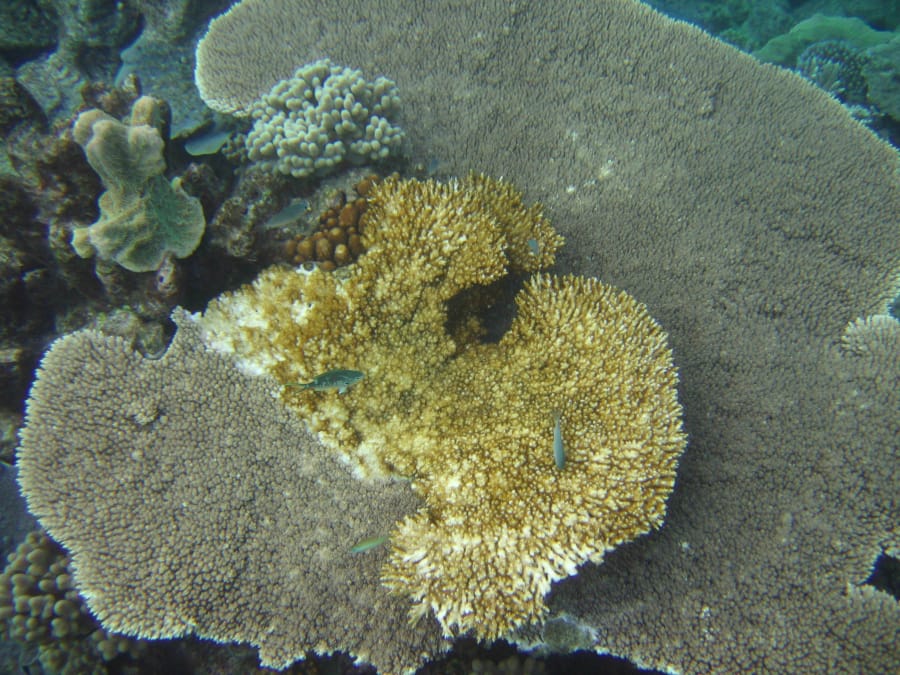

Bleaching, though, isn’t the same as coral death. When symbiotic algae leave corals’ bodies and the animals then turn white or “bleach,” they can still bounce back if environmental conditions improve. The Great Barrier Reef has seen major bleaching in some of its sectors — particularly the more isolated, northern reef — and the expectation has long been that this event would result in significant coral death as well.

Now some of the first figures are coming in confirming that. Diving and aerial surveys of 84 reefs by scientists with the ARC Center of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies at James Cook University, in Australia — the same researchers who recently documented at least some bleaching at 93 percent of individual reefs — have found that a striking 35 percent of corals have died in the northern and central sectors of the reef.

The researchers looked at corals from Townsville, Queensland, all the way to New Guinea, said coral expert Terry Hughes, who led the research – and examined 200,000 corals overall, he said. The 35 percent, the researchers said, is an “initial estimate” that averages estimates taken from different reef regions.

“It varies hugely from reef to reef, and from north to south,” said Hughes, who directs the ARC Center. “It basically ranges from zero to 100. In the northern part of the reef, 24 of the reefs we sampled, we estimate more than 50 percent mortality.”

Fortunately, the southern sector of the reef was largely spared, thanks to the ocean churning and rainfall caused by Tropical Cyclone Winston, which cooled waters in the area, Hughes said. In this region, to the south of the coastal city of Cairns, mortality was only about 5 percent.

But while coral death numbers are far lower to the south, “an average of 35 percent is quite shocking,” Hughes said. “There’s no other natural phenomenon that can cause that level of coral loss at that kind of scale.”

He noted that tropical cyclones — what Americans call hurricanes — also kill corals at landfall, but typically over an area of about 50 miles. In contrast, the swath of damage from the bleaching event, he says, was “500 miles wide.”

“This coral bleaching is a whole new ballgame,” said Hughes.

The ARC Center released a map to accompany its findings, demonstrating the areas sampled and the extent of coral death found.

The news comes just days after the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, an Australian government agency, similarly noted that “In the far north, above Cooktown, substantial coral mortality has been observed at most surveyed inshore and mid-shelf reefs.”

There has already been widespread attribution of this record bleaching event to human-caused climate change. One recent statistical analysis, for instance, gave extremely low odds that the event would have happened by chance in a stable climate. It was caused by record warm March temperatures in the Coral Sea, more than 1.8 degrees Fahrenheit above average.

The bleaching event is the third and worst such strike on the Great Barrier Reef — other major bleaching events occurred in 1998 and 2002. Thus, the reef has bleached three times in the past two decades.

“So the question now is, when are we going to get the fourth and fifth bleaching event, and will there be enough time, now that we have lost a third of the corals, for them to recover before the fourth and fifth event?” Hughes asked.

In the case of at least some of the corals, the answer is probably no. Some dead corals were 50 or 100 years old, making it hard to see how these kinds of animals could grow back before another shock to the system arrives.

Indeed, the aforementioned statistical analysis suggested that by the year 2034, a March with sea temperatures as warm as occurred in 2016 could happen every other year, as the planet continues to warm.

And what is happening to the Great Barrier Reef this year is just one part of a much broader global episode.

“Unfortunately, there are islands in the central equatorial Pacific Ocean like Christmas Island where the effects have been even more catastrophic — over 80 percent mortality,” said Mark Eakin, who coordinates the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Coral Reef Watch.

“It is essential to remember that even those corals still alive have a higher risk of dying from disease and have lost at least a year’s reproductive season and growth,” Eakin continued. “Even the corals that ‘only’ bleach are severely harmed by events like this one.”

The damage to the Great Barrier Reef — a major tourist icon — has led to intense climate-focused debate in Australia, which is on the verge of an election on July 2.

But for scientists, the idea that something abnormal is happening seems hard to escape.

“We seem to have gone from an era when mass bleaching was unheard of, to the modern era where it has now occurred three times in 18 years,” Hughes said.