An adorable discovery made with the leadership of a Washington State University Vancouver student could have real implications for the medical field.

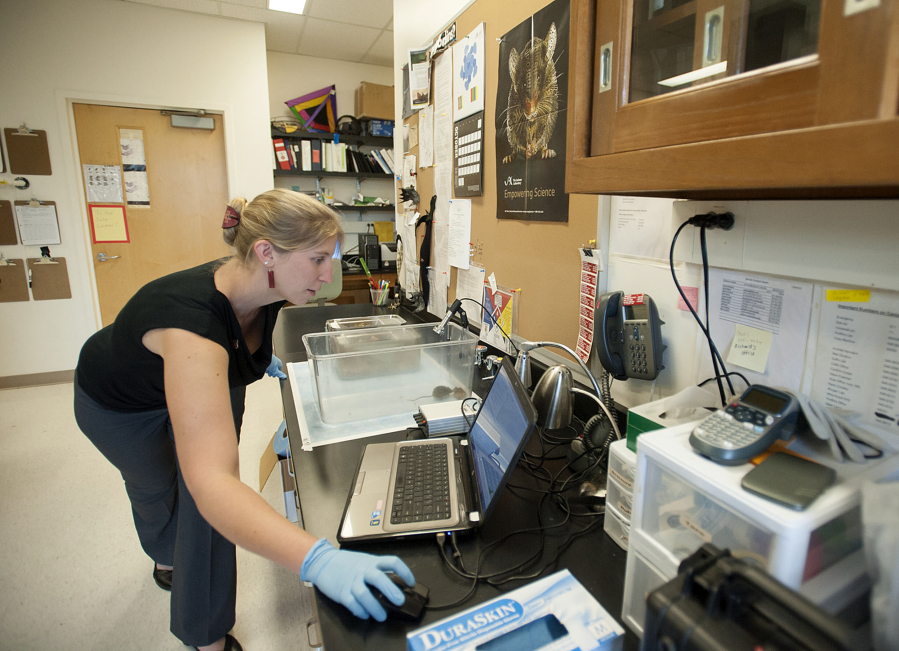

Elena Mahrt, a 29-year-old zoology doctorate student at WSU, helped lead an international team of researchers to study the way mice make ultrasonic sounds — or “love songs,” as scientists affectionately call the crooning sounds male mice make to woo females.

It’s long-standing knowledge in the scientific community that mice make these sounds, too high-pitched for the human ear. But until now, they have not known how they do so.

Mahrt, along with a researcher from the University of Cambridge, University of Washington and University of Southern Denmark, have discovered that mice whistle using their windpipes, bypassing their vocal cords entirely. The study published in Current Biology describes how mice force a small jet of air from their windpipe against the wall of the larynx, producing the whistling noise.

Mahrt and her adviser, Christine Portfors, assure that the research, besides being cute, could change the way doctors treat conditions that affect speech.

“What we are trying to understand is how humans communicate,” Mahrt said.

The research, funded by the National Science Foundation and the university, allowed researchers to genetically modify mice to compare how certain genes can affect speech patterns. Mahrt uses autism as an example. By tweaking a mouse’s genes to replicate human autism, scientists can study how their ability to vocalize changes.

“For many people, sometimes things don’t quite go right,” Mahrt said. “Their social behaviors are different. We don’t understand why is that going on in the human brain. We’re able to recreate this problem in a mouse model.”

Ultimately, that could lead to finding better treatments for children who aren’t meeting their speech milestones, Portfors said.

“If we can understand we can develop better therapies for kids who have speech problems,” she said. “That’s really the big picture.”

Mahrt, who began her doctorate in 2010, is slated to complete her studies later this year. Her research focuses on understanding how the brain processes sound. She’ll defend her dissertation on the subject next month.

This represents a shift for Mahrt, who originally began her college studies intending to be a chiropractor. But a research project looking at the sounds bats make in social contexts as an undergraduate student “opened the door” to a greater world of science and research.

“I enjoy working with people,” she said. “That’s why I like science, because the people are the best to work with.”

As an added bonus to making a significant scientific discovery, Mahrt had the opportunity to travel to Denmark to work directly with senior author Dr. Coen Elemans, head of the Sound Communication and Behavior group at the University of Southern Denmark. That’s a rare opportunity for a student researcher, according to Portfors.

“In other cases, it’s usually the head of a lab who does all the traveling,” Portfors said.

Mahrt said she was grateful for the collaborative opportunities the university has and encouraged.

“You cannot be the lonely person in the ivory tower that does all the work,” Mahrt said.