Imagine if the parts under the hood of your car were made in layers of color like jawbreaker candies. As the parts become worn, the changing colors would alert you to wear and tear.

Or imagine one finicky piece breaks and, rather than scouring parts stores or junkyards, you look up the replacement online and press “print.”

The bridge between now and then could develop sooner than you think.

HP Inc., the Palo Alto, Calif.-based printing company, released last fall its Jet Fusion 3D 4200, an obsidian-colored printer nearly the size of a Smart Car. It reportedly prints 10 times faster than its peers in a growing industry that, according market research firm Wohlers Associates, was last year doing $7.3 billion in business. HP’s own research pegs the industry closer to $6 billion.

Unlike the typical 2-D inkjet printer that costs less than $100 today, the industrial 3-D printer costs $200,000 to $250,000. That would obviously be a prohibitive price for most individuals, but HP has its sights set on manufacturers.

“This isn’t about HP shipping a product into an existing $6 billion 3-D printing scene,” said HP spokesman Noel Hartzell. “This is taking on the injection molding category,” as well as other processes that have been linked to manufacturing for generations.

To do that, HP is embarking on a years-long strategy to drive down costs and raise a market where 3-D printing could become common. The company believes 3-D printing could usher in another industrial revolution by unleashing design possibilities and shortening supply chains. And much of its research and development is happening here in Vancouver.

Apples to apples

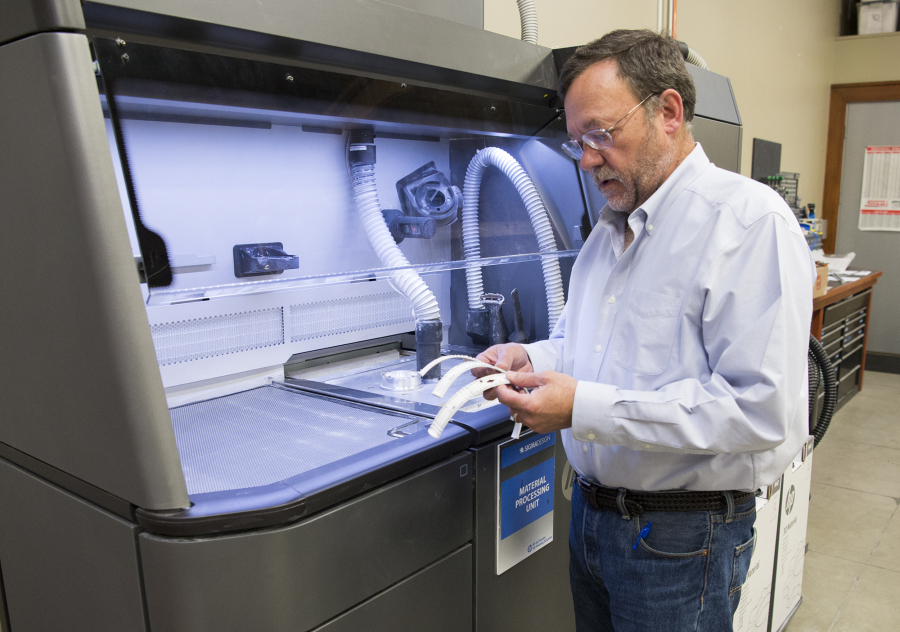

In the back room of Sigma Design’s Vancouver office, an HP 3-D printer whirs in low tones while it builds small parts from a nylon polymer. Nearby are printed tchotchkes including a toy motorcycle, a cog and a functioning pair of scissors.

Sigma Design, a product design and engineering firm led by former HP employees, recently landed a job building a specialized product: a device that labels fruit faster and with less waste.

“It’s a product we designed for a client and they will sell it to the food packing industry in Washington — the apple industry,” said Matt Cameron, vice president of engineering for Sigma Design.

The company will build 60 labelers, turning to the 3-D printer to make 12 of its many unique parts, which themselves vary in size and quantity.

“So we’ll print 400 of some of these little parts, and in other cases it’s just one (part per device), so we print 60. Some are the size of a coffee cup or the size of a pen cap,” Cameron said, adding that other parts of the labeling machine will include metals and injection-molded plastics.

The job is right in the 3-D printer’s wheelhouse. The technology has in the past been too slow for anything beyond prototyping, but experts say this latest printer offers a sweet spot for replicating hundreds or thousands of a single item — though higher volumes still lend themselves more to injection molding.

“It’s still competing against injection molding, which is fast and cheap. But particularly if you’re going to change the design each time or produce small amounts, then that’s where 3-D printing comes in. And now it’s going to be much faster,” said Jack Beuth, a mechanical engineering professor and director of the NextManufacturing Center at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh.

Cameron added that now with the 3-D printer in their inventory, Sigma Design has a stronger capacity for manufacturing.

“It’s not what we started doing … but we’ve definitely moved into the manufacturing side of things and it feeds in well with our main business,” he said.

Local innovation

While 3-D printing has been around since the 1980s, it only recently gained momentum after companies took advantage of expiring patents, according to Beuth. Costs dropped for a time, but sales in recent years stagnated as consumer interest plateaued.

HP, which came to Vancouver in 1979 and started the inkjet revolution, appears poised to reignite that growth. With decades of printing experience and a trove of intellectual property, the company set out to find moves to make that would set the business’s foundation in the future, according to Scott Schiller, vice president and global head of market development.

“That was a huge effort. More than $1 billion (was) invested into getting that initiative going in the early 2000s,” said Schiller, who joined the company in 2003 to oversee new product development. It’s similar to how Apple Inc. found its second and third acts by pinning its technology to music and smartphones.

What came about was a souped-up version of existing print technologies. In HP’s 2-D printer, an apparatus whizzes across a paper surface while superheating and condensing material. The 3-D printer would more or less need new data processing systems to handle three dimensions, and replace ink with polymers and chemical agents.

The technology’s long-term potential, Schiller said, is linked to innovation. Building products from the ground up — known as additive manufacturing — allows for new advances that weren’t available by carving from larger pieces. The multicolored layers of car engine parts is one example.

“Imagine that you have a rainbow color-changing through the volume of the part, such that if you cut it at a cross-section, you can see the colors of the rainbow changing,” he said. “There was no design tool in the world able to do that.”

Innovations are already apparent in non-manufacturing industries. Some hospitals invested in 3-D printers and fabricate their own models of organs or CT scans to visualize medical procedures. Entrepreneurs are trying to build entire car bodies that aim to be lighter and more durable than steel and plastic. Earlier this year, a video that made the rounds on Facebook showed a house being printed.

“It is such a mindset shift,” Schiller said. “It’s a massive shift in how people have thought about what constrains design.”

Open market

Still, 3-D printing remains at the whim of economic forces. History shows that prices of new technologies are driven down by competition, which won’t occur until the technology is proven to make products quickly, cheaply and at high quality, Schiller said.

To address this, HP launched in March a laboratory in Corvallis, Ore., where it will work with large manufacturers to develop new technologies and materials that will work with its existing 3-D printing technology. Those manufacturers included Nike, Johnson & Johnson and German chemical company BASF.

“It was really about getting the industry engaged to pursue this opportunity jointly,” Schiller said. “The idea is that we’ve got a platform where others can provide materials for that platform and let the market and the world take advantage of that.”

The idea essentially crowd-sources research and development to find cheaper, faster and stronger ways of 3-D printing. The lab strives to make sure those breakthroughs happen in HP’s kitchen. Hartzell and Schiller declined to get into specifics, but they compared it to Apple’s App Store, where developers can market new applications that harness the iPhone’s proprietary technologies.

It remains to be seen how long it will take everything to catch on, but Hartzell and Schiller are convinced 3-D printing will one day be a workhorse. It could someday be an appliance where one could build everything from electronic circuits to screws.

“I would take it one step further,” Schiller said. “Why do you need the screw?”