SEATTLE — It’s a little easier now.

But back in the early ’90s, someone died every 72 hours at the Bailey-Boushay House in Seattle’s Madison Valley.

AIDS. It was always AIDS. The year that Bailey-Boushay opened, it was the No. 1 cause of death for men aged 25 to 44 in the U.S. Half the people who died of AIDS in King County died at the facility.

Wendy McNerthney was there for almost all of them, bearing witness to one of the worst health-crises the country had ever seen.

“It was like a plague,” McNerthney, 64, said recently. “I just thought, I can take it one day at a time, one hour at a time. Many times I came home sobbing. But, I thought, ‘I can’t walk away.'”

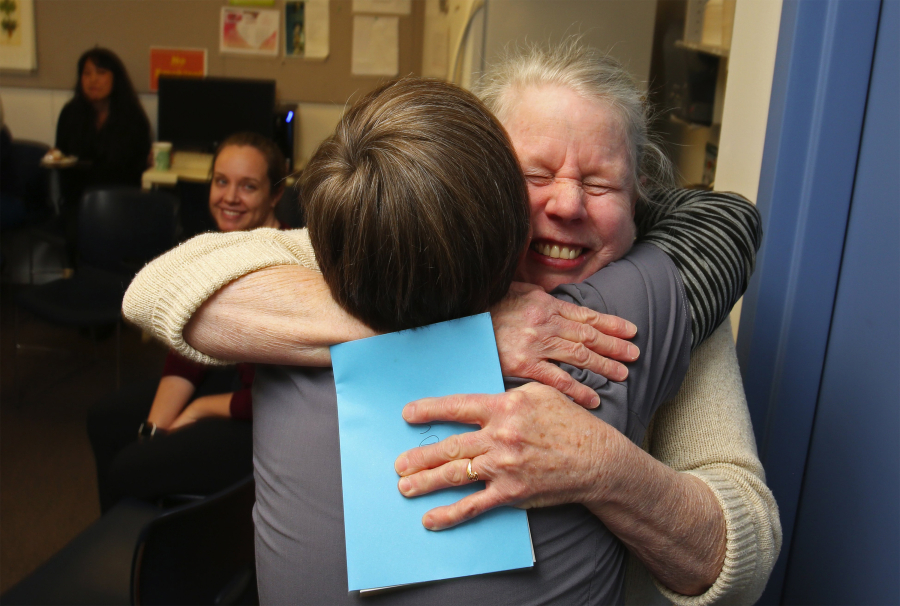

After more than 24 years, though, McNerthney has retired from Bailey-Boushay. She was the longest-serving nurse the facility has had, having spent more than two decades tending to patients and sitting with partners who would eventually become patients themselves.

She comforted relatives who would come straight from the airport or the road, struggling to absorb what came in three, stunning blows: Their son was gay. Their son was sick. Their son was dying.

“It’s such a delicate moment,” McNerthney said. “I would say, ‘No matter what, put all that aside. He’s your son. You’ve got hours or days to tell them you love them.'”

Executive director Brian Knowles is going to miss that gift: “Wendy just looks around at everyone in the room and understands what they need,” he said. “And that is a very special thing.”

McNerthney arrived at Bailey-Boushay in October 1992, six months after it opened — the first facility in the country devoted to end-of-life care for people with AIDS.

She had taken her nursing exams in July of that year, and while she waited for her results, worked as a graduate nurse at a nursing home in North Seattle.

But she kept thinking about the patients at Bailey-Boushay, a place she had heard about from one of her professors.

“It sparked my curiosity,” she said. “I thought, ‘What a need for nurses, to help these people. And how wonderful to have a home for them.’ They needed compassionate, caring nurses to care for them at the end of their lives. And I needed to learn more about AIDS.”

She arrived to find patients ranging in age from their 20s to their 70s. The average stay was four to six weeks, during which 80 percent of the patients burned with fevers that reached 103 degrees.

For the first four years she was there, no patient was ever discharged. They just died. One every 24 to 72 hours, adding up to about 300 deaths a year.

McNerthney administered cold packs and spent night shifts making protein milkshakes with two or three blenders going at once. She touched patients with lesions caused by Karposi’s sarcoma, a cancer that developed on lymph nodes. She stayed close.

“I wasn’t scared,” she said. “You learned good standards of care — hand-washing, gloves, gowns and isolation carts. You’re just there on the front lines.”

Most of the patients came straight from hospitals.

“There was no other place,” said Knowles, the executive director, adding that some home-care agencies and hospice facilities wouldn’t accept patients with AIDS. If they did, those patients received minimal or no care at all. Nurses refused to touch them. Dietary workers refused to go into their rooms and left their food trays stacked by the doors.

At Bailey-Boushay, 35 patients received round-the-clock care and were even allowed to bring in their own furniture. One patient’s room was featured in Metropolitan Home magazine.

Knowles called McNerthney “a connector.”

“She remembered everybody, and all the years she has been here, the sensitivity and the warmth,” he said. “She is so genuine. And when she looks at you, you can tell she’s right there with you. You can see it on her face.”

McNerthney was born in Winnipeg, Manitoba, and moved to Everett as a child. Her mother died when she was 15, and she looked after her younger siblings.

She was raised Lutheran, but religion didn’t matter to her when it came to caring for people who had been condemned from the pulpit, by politicians and by people in McNerthney’s own circle.

“I had no moral struggle with the disease,” she said. “It’s the people you were taking care of. So it was all about education.

“I wasn’t stern; I just quietly educated people who had valid questions. These aren’t AIDS patients. They are patients with AIDS.”

She trained nurses who were new and nervous. Protect yourself, she told them.