LOS ANGELES — He was a retired Los Angeles County Superior Court judge who became an unlikely American TV icon, a white-haired jurist who was dubbed the “Solomon of Small Claims.”

Judge Joseph A. Wapner, who presided over “The People’s Court” for 12 years in the 1980s and ’90s, has died, a family member told The Associated Press. Wapner was 97.

David Wapner said his father died Sunday at home in his sleep. He said his father was hospitalized a week ago with breathing problems and had been under home hospice care.

Launched in syndication in 1981, “The People’s Court” featured actual cases drawn from small claims courts in the Los Angeles area: real plaintiffs and defendants who agreed to dismiss their court cases and have their disputes settled in a courtroom setting in a Hollywood TV studio by Judge Wapner.

The cases Wapner heard were typical small claims disputes, such as a case involving a cat that was supposed to have been dyed blue to match its eyes but came out pink.

Or the man who bought a beer for 75 cents that he said was flat, but the store owner refused to give him another beer or return his money.

Or the woman who bought a birthday cake for her daughter for $9, discovered it was moldy and the baker would only refund $4.50.

In appearing on the show, the litigants agreed to abide by Wapner’s decision. Money for winning plaintiffs came out of a fund provided by the producers — $800 for each case when the show debuted. If a plaintiff lost, each party received $400.

The half-hour show, served up five days a week with real-life retired bailiff Rusty Burrell and Doug Llewelyn introducing each case and conducting post-decision interviews with the litigants, struck a chord with viewers.

By 1989, “People’s Court” was airing on more than 175 stations and drawing a daily audience of 20 million.

That same year, a Washington Post poll showed that Wapner was the best-known judge in America.

He was parodied on “Saturday Night Live” by Phil Hartman, and his name frequently cropped up in Johnny Carson’s monologues on “The Tonight Show.”

Time magazine reported that U.S. Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall occasionally “can be found in his chambers chuckling” while watching “The People’s Court.”

And Dustin Hoffman’s autistic savant character in the 1988 movie “Rain Man” famously fretted over missing the show. (“Uh-oh. Fifteen minutes to Judge Wapner, ‘The People’s Court.’ “)

Wapner, whose 20-year career on the bench included an early stint in small-claims court in Los Angeles, believed the show did more than entertain viewers.

“I’m trying to demystify the whole process,” he told The Washington Post in 1989. “Make it simple, make it palatable. I want people to have respect for the law, and I want to educate people on the basics of the law.”

His status as a grandfatherly folk hero — he received a standing ovation when he addressed law students at Harvard and fielded autograph requests whenever he appeared in public — was an unexpected bonus for Wapner.

“I still can’t believe it,” he said in a 1989 interview with the Chicago Tribune. “I’m just an ordinary judge from California.”

Wapner was not long retired from the bench when TV producers Ralph Edwards and Stu Billett were searching for a real judge to preside over their proposed courtroom show.

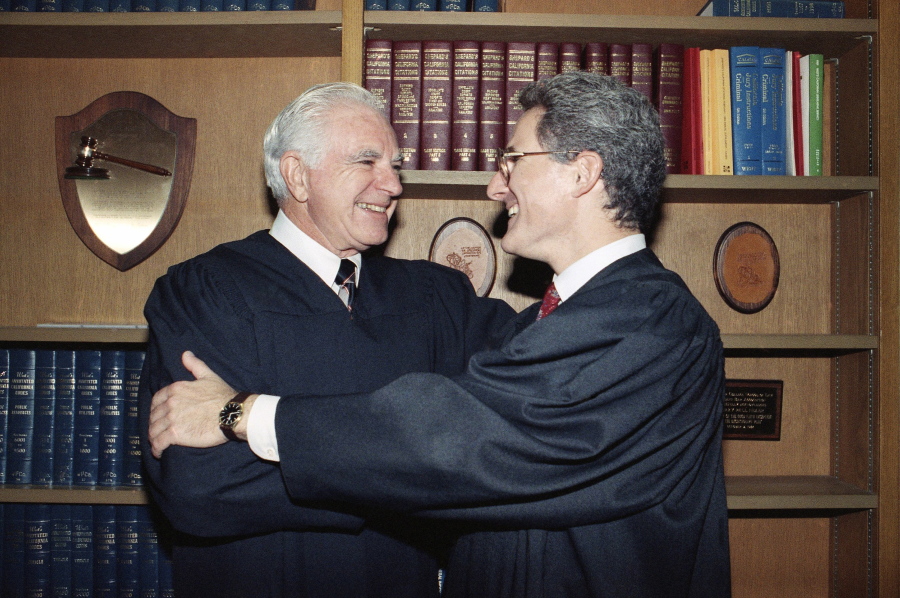

Superior Court Judge Christian E. Markey Jr., a friend of Edwards, suggested his former colleague and longtime tennis partner.

“Judge Wapner turned out to be even better than what I wanted,” Billett said in a 1986 profile of Wapner in the New Yorker. “When Joe walked in the door, I thought I was looking at Tyrone Power, and I said to myself, ‘My God, I hope he’s good.’ He’d come with such aplomb and such credentials.”

In 2009, more than a decade after stepping down from his TV bench, Wapner received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

“He was the perfect choice to kick off this genre,” Harvey Levin, then the host and legal reporter on “The People’s Court,” said during the ceremony. “If today, you could look at who is it that would be the right person with the right tone and the intellect and the passion and the compassion, it would be Joe Wapner.”

Marilyn Milian, then the presiding judge on “The People’s Court,” said at the ceremony that Wapner “will always be the gold standard to which the rest of us seek to practice, because you started this whole genre by serving order and justice out of human chaos.”

The son of a lawyer, Wapner was born Nov. 15, 1919, in Los Angeles and graduated from Hollywood High School in 1937. As a senior, he briefly dated future Hollywood star Lana Turner, a beautiful fellow student then known as Judy Turner.

On their first date — for Cokes after school at a nearby drugstore — she wound up paying the bill when Wapner discovered he had no money. The budding relationship soon ended when they went on a double-date to a school dance. As Wapner told the New Yorker: “She dropped me.”

Although he had ambitions of becoming an actor and wanted to study drama at what is now called Los Angeles City College, Wapner’s strong-willed father talked him into going to the University of Southern Californian instead of studying acting.

A philosophy major, Wapner graduated from USC in 1941 and soon was serving in the Army in the South Pacific during World War II. As a lieutenant commanding a platoon in the 132nd Infantry Regiment of the Americal Division, he received a Bronze Star for valor and a Purple Heart.

Returning to USC after the war, he received a law degree in 1948 and was admitted to the bar the next year. He practiced law with his father for three years before going on his own.

He and his wife, Mickey, whom he married in 1945, had three children, Sarah, David and Frederick. Both of his sons became lawyers.

In 1959, California Gov. Pat Brown appointed Wapner to municipal court. Brown elevated Wapner to the Los Angeles County Superior Court in 1961. He was presiding judge when he retired in 1979.