Those missing First, Second and Third Plains? They’re just part of a system of topographical references that evolved more than 150 years ago around what’s now the Fort Vancouver National Historic Site.

Allow us to ex-Plain: After regional Indian tribes used this stretch of the river for centuries as a commercial crossroads, Fort Vancouver became the Northwest hub of the Hudson’s Bay Company’s fur-trading empire.

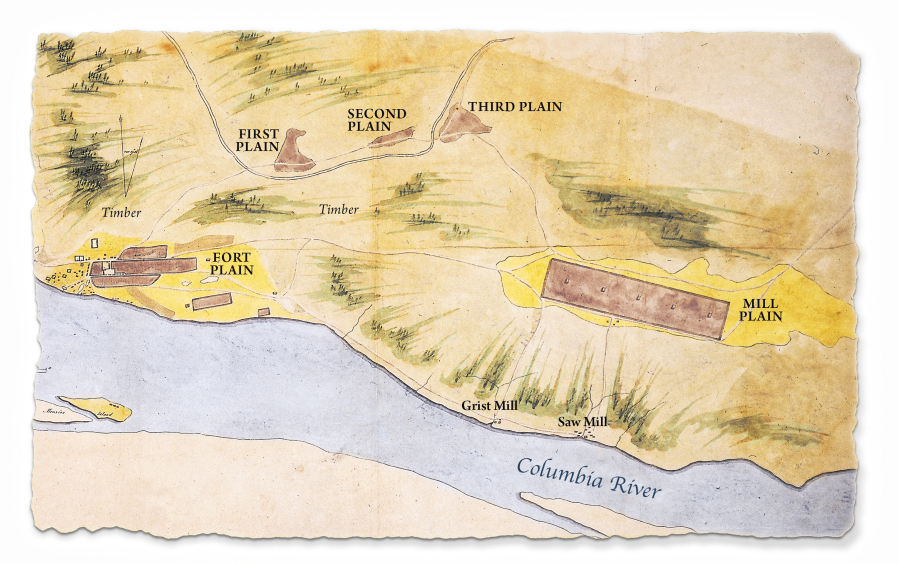

When the new occupants got around to mapping the neighborhood, they took note of several open meadows scattered among the nearby forest. They referred to them as plains.

Some of the plains were the result of tribal land-management practices. The native people shaped the landscape by burning prairies and meadows to increase plant and animal diversity and to improve conditions for hunting and harvesting, according to a National Park Service interpretive panel on the Vancouver Land Bridge.

An 1846 map drawn by Richard Covington designates several areas east and north of the fort as “Plains.” Covington (he and wife Anne built the Covington House) sketched out the shapes and dimensions of First, Second, Third and Mill Plains on his map, which is now at the Washington State History Museum in Tacoma.

A much more recent illustration shows the location of nine Plains, overlaid on a map of present-day Clark County. The map was created by Jim Pestillo, a volunteer at the Clark County Historical Museum.

Plain near the mills

Pestillo’s series of Plains starts near the Columbia River, where the Hudson’s Bay Company built its post at — what else? — Fort Plain, which extended from the stockade to the east.

According to a 1992 Park Service publication, Hudson’s Bay’s principal operations took place “on three large natural plains named Fort Plain, Lower Plain and Mill Plain,” which was named for the grist mill and saw mill about a mile to the south, along the river.

Lower Plain was on the opposite side of Fort Vancouver, a lowland that extended west from the stockade.

Further west, there are references to Dairy Plain; it is not designated on Covington’s map, but he did sketch in a dairy, about 1 1/2 miles west of the fort, and extensive pasture land near the current location of the Port of Vancouver.

According to the Park Service report, Dairy Plain and Lower Plain “lay to the westward of Fort Plain, but exactly where one left off and another began no one seems to have said.”

A Park Service historian described Mill Plain as the largest cultivated area in the Fort Vancouver farming operation, measuring about three miles by an average of three-quarters of a mile. On today’s map, it was in the vicinity of Mill Plain Boulevard, between 104th and 164th avenues.

Three names survive

Periodic farming was done at six additional open areas, collectively known as the Back Plains. First Plain (near the current site of Eleanor Roosevelt Elementary and Bagley Park), Second Plain (just east of the current site of Andresen Road near Burton Road), Third Plain (an area now south of Vancouver Mall extending into the Royal Oaks Country Club) and Fourth Plain (now known as the Orchards and Sifton areas). All roughly followed the course of Burnt Bridge Creek.

Camas (or Lacamas) Plain was northwest of Lacamas Lake. Finally, there was Fifth Plain, east of Brush Prairie and south of Hockinson.

As Debbie and Ted have observed, the roads that were established to Mill Plain and Fourth Plain are still part of the community as names of major east-west thoroughfares.

The only other surviving echo of that “Plains” system is the one farthest from Fort Vancouver. You can still find Fifth Plain Creek on local maps; its lower stem crosses Fourth Plain Boulevard just east of Ward Road.

The Fifth Plain name also identified a public institution long after the Hudson’s Bay Company left town. There was a Fifth Plain School well into the 20th century. The name went away in 1929 when voters in the Fifth Plain and Hockinson school districts voted to consolidate.