MOUNT VERNON — When he was 13, Steven Anthony Rickards stabbed his little sister to death and put her body in a freezer.

Now, 16 years later, Rickards has served his time and tried to overcome the tragedy. He got a house, steady work and a family of his own.

But his juvenile conviction had prevented him from obtaining a license necessary to work as a hearing specialist at his mother’s audiology business. So he quietly asked the Skagit County Superior Court to seal his case and expunge his record, as allowed by Washington state law.

Instead, one day before his court hearing this week, the Skagit County Prosecutor, Richard Weyrich, alerted 11 news organizations that Rickards was trying to have the records sealed — and sent them a detective’s statement in support of an arrest warrant in the case, lest the details of the crime be forgotten.

“I am sending this email to the media due to the fact that this office believes a change needs to be made by the Legislature as it relates to the sealing and vacation of convictions of certain crimes by juveniles,” he wrote. “While this office is sensitive to juveniles being able to rehabilitate themselves and have their records sealed, this is not one of those cases.”

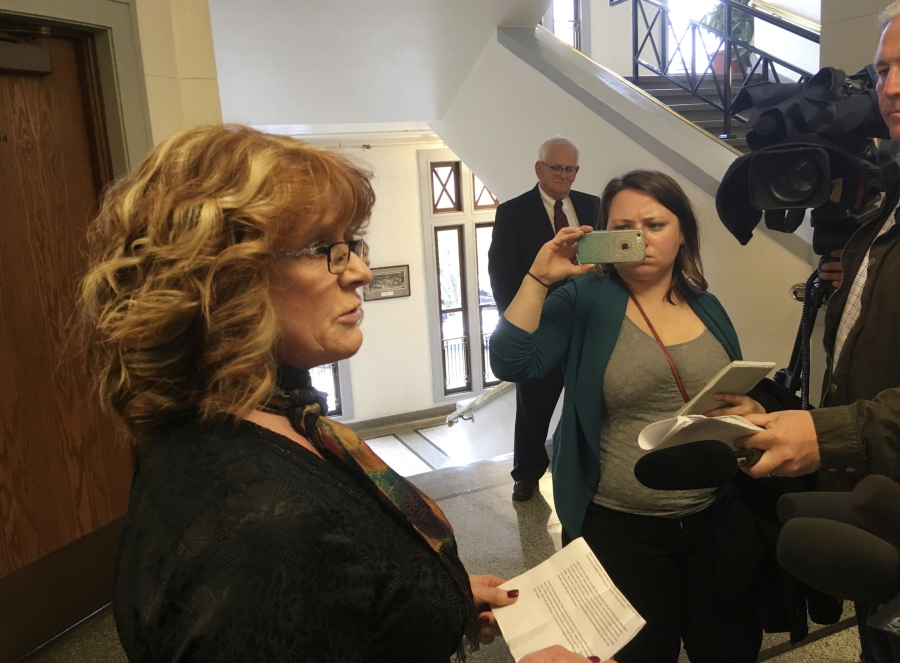

And when Rickards’ mother, Diane Fox, and his attorney, Corbin Volluz, exited the courtroom Thursday afternoon, they were met by a throng of television news cameras and reporters, for whom they expressed their outrage at the prosecutor’s actions. Volluz said the prosecutor’s actions may have broken legal ethics rules as well as state law, which prohibits the dissemination of juvenile court records except in certain circumstances.

“If Mr. Weyrich wants to change the law, let him go to the Legislature and change the law,” Volluz said. “He needs to uphold the law as written and not subvert it.”

The judge on Thursday agreed to seal the records, but delayed for a month a hearing on whether to vacate the conviction, in a case that now highlights the extent to which the law should accommodate the rehabilitation of even the most serious juvenile offenders.

Weyrich said after the hearing he did not believe he had violated any ethical rules, but declined to discuss further whether the release of the arrest warrant declaration was improper under the law. He said he doesn’t know anything about Rickards, but that it was in the public interest for information about his crime to be available.

“There are certain types of crimes that should not be sealed,” he said.

Rickards, 29, pleaded guilty in 2002 after telling investigators he had killed his 8-year-old sister, Samantha, because he felt suicidal but didn’t believe he could kill himself. Experts determined he had suffered a psychotic break, his mother said Thursday.

Under Washington law, those convicted of even serious crimes, except for rape, may seek to have records of their cases sealed if they meet certain conditions, such as not committing any crimes for five years after their release and paying restitution. In addition, while juvenile court records are generally public, state law prohibits the dissemination of certain records — even where such records are located in public court files.

So even though any reporters who wanted to review Rickards’ case before Thursday could have — and even though news organizations published Rickards’ name and the details of his crime after it happened — it was forbidden for the prosecutor to email the detective’s arrest warrant application to reporters, Volluz argued. The arrest warrant application was stamped “Confidential Information” and noted “Secondary Dissemination Prohibited Unless in Compliance” with state law.

For Rickards’ mother, it’s been painful to relive the case in court.

“The grandstanding on the prosecutor’s part is at the cost of crushing my family and myself once again,” Fox said. “There are no other victims in this case. There was my daughter that I lost. There was my son that I lost for over seven years. We are the victims here.”