“Where’s the fuel truck?” the pilot asked as he guided his small turboprop plane to its assigned spot at the Jacksonville, Florida, airport. It was Oct. 4, 1971.

“This is the FBI,” the control tower responded. “There will be no fuel. Repeat. There will be no fuel.”

Minutes later federal agents rushed the plane.

The result: George Giffe, the suicidal man who had hijacked the private aircraft in Nashville — and demanded that it be refueled on Jacksonville’s tarmac — shot the pilot to death. He then did the same to his estranged wife, Susan Giffe, who he had kidnapped earlier in the day. He killed himself as well.

The terrible tragedy came in the midst of a skyjacking epidemic in the U.S. In just four years, more than 100 aircraft had been seized, knocking the FBI on its heels. In Jacksonville, the bureau had finally decided to get aggressive — and it proved disastrous. It also, just possibly, provided the spark for what would become one of the greatest mysteries in modern law enforcement.

The bloody outcome of the FBI’s Jacksonville raid, New Hampshire engineer Bill Rollins believes, inevitably led to the most famous skyjacking of all time. Fifty-one days after the Florida murders, a well-dressed, middle-aged man calmly took over a Northwest Orient flight out of Portland and parachuted out over Washington state with $200,000 in ransom loot.

That’s right. Rollins, an inventor and a licensed pilot, is convinced he’s solved the 46-year-old D.B. Cooper case. The man who called himself Dan Cooper when he purchased a plane ticket on November 24, 1971, Rollins says, was Joseph S. Lakich, who died earlier this year at age 95. He was the father of Susan Giffe. Lakich’s objective with the skyjacking: to make the FBI look bad.

Rollins’ deduction is a surprising one: Joe Lakich hasn’t been on the radar of any of the “Cooper” obsessives over the years — including, it appears, the FBI agents pursuing the case.

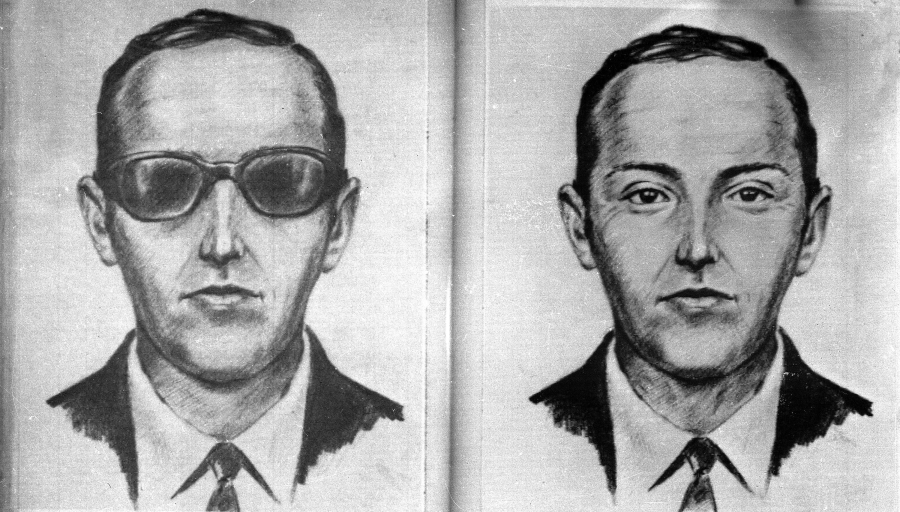

The hijacking of Northwest Orient Flight 305 is one of the best-known and most hotly debated unsolved crime cases in U.S. history, right up there with the Black Dahlia murder and the disappearance of union leader Jimmy Hoffa. Songs and books have been written about the unknown skyjacker. Treat Williams starred in a fictional 1981 movie about him. Scores of amateur investigators — known as Cooperites — have been chasing leads for years. Popular suspects among the case’s sleuths include the late Richard Floyd McCoy, who was convicted of a 1972 United Airlines hijacking, and disgruntled Vietnam War veteran Robert Rackstraw.

Rollins’ conclusion is an outlier. Available hard evidence shows Lakich to have been a good citizen and a patriot, not a daring criminal. Rollins’ theory, it must be remembered, is only that, a theory. But it’s a compelling, carefully considered one. He reached his verdict, he says, by looking at the case from a different angle.

“I figured it out because I understood the emotions,” he told The Oregonian recently. “No amount of science is going to get you to this man because he didn’t leave enough evidence.”

But Rollins did use some science — and his engineer’s logic — to determine how Cooper might have gotten away with his heist. And that’s what caught the interest of longtime Cooper chaser Bruce Smith.

“Bill is an interesting guy,” says Smith, the editor of The Mountain News in Washington state and the author of “D.B. Cooper and the FBI: A Case Study of America’s Only Unsolved Skyjacking.” “His theory about how Cooper planned and orchestrated [his getaway] is creative, out-of-the-box thinking. I think it’s sublime.”

Before he settled on Lakich as his man, Rollins decided the hijacker must be a real-life MacGyver. He figured “Cooper” planned the undertaking with military precision. That plan, he surmised, would have included a Zodiac boat tied up on the Columbia River near Portland’s airport; the kind of relatively compact distance-measuring device that was just becoming available at the time; the well-lit Merwin Dam as his lodestar; a pickup truck with a camper left out in the woods before the hijacking; and, perhaps most important of all, poor weather to keep the chase planes from seeing him leave Northwest Orient’s Boeing 727. Last year, Rollins produced a short e-book and a 7-minute video that laid out his Cooper escape theory and asked the skyjacker to contact him. You can watch the video below.

The possible escape clearly fascinates Rollins, but it was his take on the personal aspect of the story that drove him on. He believed D.B. Cooper was not a career criminal — indeed, that Cooper wasn’t even interested in the ransom money.

“All I knew is I was looking for someone who had suffered a tragedy and had a grudge,” Rollins says.

This supposition about motive came from an interview that federal agents conducted with Tina Mucklow, one of the Northwest flight attendants, who recalled asking Cooper if he had a grudge against the airline. Cooper’s response: “I don’t have a grudge against your airline. I just have a grudge.”

Rollins, who began his investigation in earnest only last year when he heard the FBI had officially abandoned the Cooper case, decided the hijacker was a decent man who had been pushed over the edge by some terrible event.

He looked for people who might have been angry at aviation officials or federal law enforcement or the U.S. government in general. He investigated family members of victims, ranging from the Kent State shootings to commercial-airline crashes of the era to various other possible triggers.

He finally came to the Jacksonville debacle — and Joe Lakich. Everything, Rollins says, lined up perfectly. (Below you can watch a trailer for a proposed documentary about the Nashville-Jacksonville hijacking and the FBI’s botched response. Rollins is not involved in the doc.)

Joe Lakich had a successful military career, serving in World War II and retiring as a major in the 1960s — experience that suggested to Rollins that he was a man who could pull off a difficult operation like the Northwest Orient hijacking. Rollins also learned that Lakich in 1971 was a production supervisor at Nashville Electronics, which fits with the recent blockbuster Citizen Sleuths discovery that the necktie Cooper left behind on the plane contains “more than 100,000 particles of rare-earth elements.” (Nashville Electronics no longer exists, frustrating Rollins’ attempts to find out if Lakich was at work the week of the hijacking.) And unlike Rackstraw and some other suspects, Lackich’s age and appearance line up with descriptions of the hijacker.

The linkage isn’t actually perfect. Considering the high level of planning required according to Rollins’ theory, it doesn’t really fit that Lakich lived and worked in Tennessee — more than 2,000 miles from Portland — and that the skyjacking happened less than two months after his daughter’s death. “There’s a lot of implausibility there,” Bruce Smith says, before pointing out that the same can be said about all of the other suspects who have received significant attention from the Cooperites.

Rollins believes it’s all about motive, about the grudge. Lakich was appalled at the incompetence of the FBI agents who undertook the Jacksonville airport operation — and at their galling response when the maneuver went south.

A 1971 Washington Post article about the events, headlined “The FBI Bungles Hijacking,” includes this stunning detail:

“Shortly after the shootings, sources say, someone in the control tower cracked: ‘You can’t win ’em all.'”

Wright, who was a pallbearer at Susan’s funeral, isn’t sure what to make of Rollins’ theory that Lakich was D.B. Cooper. “I just couldn’t tell you,” he says. “I couldn’t say what [Lakich] was capable of. You never know.”

He adds that Lakich was in “excellent shape. He was extremely fit. You could tell he was a military person, that’s for sure.”

This much also was for sure: Lakich struggled to accept his daughter’s death. In 1971, Susan Giffe was a charming 25-year-old mother and teacher who, when she was a senior in high school, had been declared “Miss Adorable” by her classmates. She reportedly had a deep bond with her father.

Adding insult to Lakich’s emotional injury: The FBI refused to admit it made any mistakes at the Jacksonville airport. (Four decades later, Nashville Scene wrote in 2009, the deadly FBI operation in Florida is taught in criminology classes “as a textbook example of how not to handle a hostage situation.”)

Rollins read through the transcripts for the trial of the kidnapper’s accomplice, Bobby Wayne Wallace, and talked to the case’s judge. He researched the successful lawsuit the pilot’s widow brought against the FBI. The horror of it all hit Rollins hard.

“I felt like it was happening to me,” he says of the pain Lakich must have experienced. “I felt deep despair. I put my head down and cried.”

He fears how this sounds. “I know, I’m a weirdo, right?”

He considered that possibility himself, he says. He wondered if he’d lost touch with reality. He shared his work with long-standing Cooperites — and received quite a lot of criticism. “They thought it sounded too James Bond-like,” Rollins says of their reaction to his theory of the escape. (The FBI, it must be noted, believes it’s likely Cooper died from his high-risk nighttime parachute leap into rainy weather, but a body has never been found.)

Bruce Smith isn’t surprised by his fellow Cooperites’ response to Rollins. “Most people who follow the Cooper case don’t like anyone who trashes the FBI,” he says. “The FBI and law enforcement are sacred cows.”

But Smith, for one, believes Rollins is on the right track.

“Bill’s identification with D.B. Cooper is extreme,” he says. “He feels like he’s, in some mystical way, communicating with Cooper. It speaks to his ‘out-thereness,’ an out-thereness that is grounded in science, in being open to the possibilities. I like that about him.”

That said, Smith doesn’t embrace Lakich as a suspect. He does, however, believe Cooper most likely was a commando or “had military connections,” and he leans toward the idea that the skyjacker didn’t do it alone — that there was an “extraction team” on the ground.

“I think the most compelling piece of evidence,” Smith says, “is Cooper himself: His smarts, his savvy, the way he handled himself during the whole thing. The dynamics of the hijacking suggest it was well-rehearsed. … This wasn’t a guy who had a few tequilas and decided to go hijack a plane.”

Another longtime Cooper chaser, Thomas Colbert, also believes the skyjacker had accomplices. Colbert is focused on Rackstraw, a former paratrooper, as Cooper.

Along with talking to Cooperites, Rollins approached Lakich’s family, communicating with a younger brother and sister, as well as his suspect’s surviving son. He says they all expressed surprise at his theory and stopped speaking with him. (Lakich’s son and sister did not respond to phone calls and text messages from The Oregonian/OregonLive.)

Rollins continued to doubt himself, ruing that he had hit upon Lakich just weeks after the man died. He tried to set aside his emotional reaction to Susan Giffe’s murder and focus on the case purely as a dispassionate investigator would. He worked up a “probability analysis” that considered “appearance, demeanor, skills, workplace, alias and grudge,” putting in all the known Cooper suspects. But no matter how many times and ways he looked at the evidence, he determined that Lakich — and Lakich alone — made sense as the skyjacker.

“From his appearance to his military training to his workplace,” he says, “he passes all the tests for D.B. Cooper.”