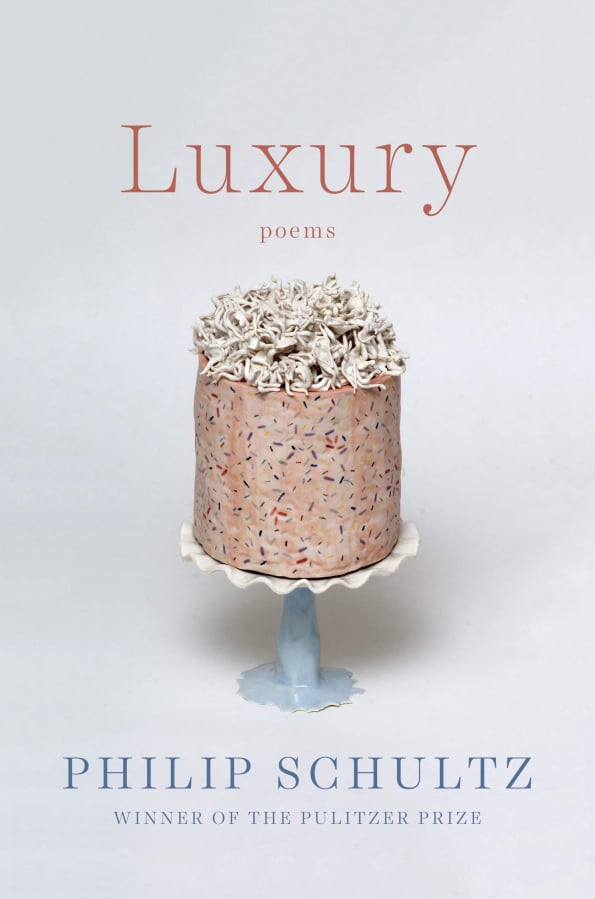

Is happiness possible or a necessary illusion? That’s one of the questions raised in “Luxury” (Norton), the compelling eighth collection by Philip Schultz. Here, he reflects on aging, the passing of time and the “past with/ all its trappings.” Yet as he looks back or considers the present, the future seems “unambiguous in its desire to elude me.” What does not escape him are the poignancy and humanity all around him — at the grocery store or the Social Security office, at the Women’s March. Small details and dramas prompt existential questions about the soul and what is necessary to live “among the relevant,/ the passionate, and the confused.” Schultz’s language is plain-spoken and the works are replete with insights and nuggets of wisdom. In the long title poem, the speaker recalls the day his father brought home a 1955 Pontiac station wagon and said, “How’s that for luxury, kiddo?” A few lines later we learn the father has had a stroke, months before his son was to go to college. He’d been working too hard, the father’s doctor tells the son, “he’s killing himself,/ only you can save him now.” Those and other memories, woven together with ideas from Albert Camus, Paul Celan and Ernest Hemingway, shape a thoughtful exploration of the philosophical and practical implications of suicide.

• Desire and restlessness are at the heart of “Wild Is the Wind” (FSG), the 14th collection by Carl Phillips, whose honors include the PEN poetry award and the Los Angeles Times Book Prize. Named after the jazz song made famous by Johnny Mathis and later Nina Simone, the book features 35 poems that counterbalance love and fear, memory and the mirage of history, despair and the willingness to hope for ideals — loyalty, wholeness, honesty. The writing dazzles with transcendent metaphors, complex connections and linguistic flourishes. It also draws on some familiar Phillips motifs — navigation and the sea, the sky and land — to explore the possibility that love can bring both stability and freedom. “The happiest/ people I know are those whose main strategy has/ always been detachment. I’ve been working on that,” explains the speaker in the poem “Several Birds in Hand But the Rest Go Free.” In “The Distance and the Spoils” he notes the “four bright points on a constellation missed earlier/ and just now seen clearly”: pain, indifference, torn trust and permission. Other emotions and factors shape this rich panoply, which consistently challenges readers without providing easy resolution.

• Jason Morphew presents a supercharged, sometimes unsettling view of domestic life in “Dead Boy” (Spuyten Duyvil), his striking debut. While many of the situations described here seem familiar — a trip to CVS, a young daughter who explodes when told it’s time for dinner — they’re presented with an edginess and sharp intelligence that makes the poems pop. An underlying tension throughout the work stems from the death of Morphew’s younger brother, whose absence is a constant presence. As the speaker explains, he “could not go where you were going” and every smile is “a figment/ of an anonymous/ mind.” The book is divided into two sections — Right Eye and Left Eye, which offer differing views of the speaker’s past and who he has become. Morphew, who began life in rural Arkansas and now holds a Ph.D. from UCLA, easily moves through a range of emotions and settings. His perspective is always surprising, as in the powerful poem “Baby in a Blender,” where he recalls how “the day after she miscarried/ again we stumbled into Macy’s/ our matrimonial blender/ was dead.”