“ … It is better to be born lucky than rich.”

That’s an expression we’ve all heard, but Lewis Sutton took genuine relief in penning those words nearly 147 years ago.

They were part of Sutton’s diary entry on Aug. 26, 1864, and the preceding sentences explained what was at stake.

“We have been very lucky on this expedition. Have not been in a battle, and have only lost one man out of the regiment.”

Sutton was a soldier in the 14th Iowa Volunteer Infantry during the Civil War, and he knew very well what could happen when the fortunes of war favored the enemy.

His younger brother, Jacob, was mortally wounded on Oct. 4, 1862, and died six weeks later.

And Sutton had been captured in 1862 in one of the war’s milestone battles, Shiloh. He returned to duty six weeks later after a prisoner exchange, and went on to fight in other campaigns as the Union Army drove into the heart of the Confederacy.

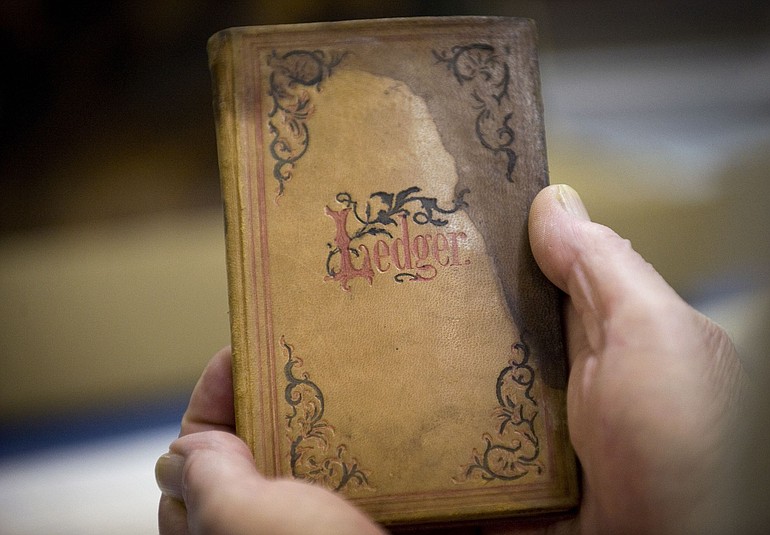

Sutton chronicled his experiences in a diary, as well as letters and regimental records that have been in the basement of the Clark County Historical Museum for 46 years.

Now longtime museum volunteer Richard Reay is carefully going through Sutton’s diary and the other material that showed up at the museum in a leather satchel a century after the Civil War ended.

“He was a clerk, although everybody fought,” Reay said.

It was Sutton’s job to pen the official battle reports and keep the 14th Iowa’s rosters. Some of those documents apparently were never forwarded to Army officials, and now are part of the museum’s collection.

There were personal items in the satchel, too, including wartime letters Sutton received from his sisters and his father who also was a Union soldier — at the age of 55. Philip Sutton enlisted in the 37th Iowa Infantry on Nov. 5, 1862, as his 19-year-old son, Jacob, was on his death bed in Iowa.

The old satchel also contained photographs of Sutton, including an image on a glass plate known as an ambrotype.

Sutton brought it all with him when he made a late-in-life move to Vancouver.

“He came here in 1893,” Reay said recently while sitting at his work table in the museum basement.

Sutton died on July 23, 1914, at the age of 75. He is buried at Park Hill Cemetery in McLoughlin Heights.

According to a tag on the satchel, his Civil War documents were donated to the museum in 1965 by Freda Sutton, his daughter-in-law.

Reay had decided to retire as a museum volunteer, but he always wanted a chance to look through the contents of that old leather satchel.

There was a padlock on the satchel, said Susan Tissot, executive director of the museum, but somebody had jotted down a brief description of Freda Sutton’s donation on a card — it was material from a Civil War soldier.

That brief description was enough to intrigue Reay. After he announced his plans to retire in January, Tissot promised to give Reay a look inside the satchel at his going-away party.

When the lock on the satchel was cut off (fortunately, it was a modern-era lock with no historical value) and the contents revealed, Reay changed his retirement plans so he could transcribe the documents.

Somebody apparently got there ahead of Reay during the past 46 years and typed out 20th-century copies of several documents. There was nothing on the pages to identify the earlier museum researcher.

Regardless of who is transcribing, it’s still Sutton’s voice describing the day-to-day life of a soldier — the short rations, the exhausting marches and the weather.

In a letter to his sister Susanna that wound up in the satchel, Sutton also offered his opinion of some fellow Union soldiers.

“Our regiment has stood the trip as well as anyone in the expedition, and better than many. When we started, the 178th New York said they were going to show the western boys how to march. They should have said they were going to teach us how to straggle, jayhawk and steal. One of the 178th New York was so near useless that when the rebels captured him, they immediately released him, saying they did not want him.”

Sutton also told Susanna that he was writing her “upon a sheet of captured rebel letter paper.”

Two years earlier, things weren’t going as well for the Iowans. In an engagement during the Battle of Shiloh, more than 2,300 Yankees were captured on April 6, 1862, at a spot called the Hornet’s Nest.

Both Lewis Sutton and Jacob Sutton are on an online list of 14th Iowa soldiers imprisoned at Camp Oglethorpe in Macon, Ga.

After they returned to duty following the prisoner exchange, Jacob was fatally wounded in Mississippi during the Battle of Corinth.

That’s the source of something that’s puzzled Reay as he has been poring over Sutton’s diary and the family letters.

“There is no mention of Jacob,” Reay said.

The younger Sutton was in the minority of Civil War fatalities, by the way, dying as a result of combat.

The 14th Iowa lost 203 officers and enlisted men during the war, Reay said — about two-thirds of them to disease.

“They lost five officers and 59 enlisted men who were killed or mortally wounded,” Reay said. “One officer and 138 enlisted men died of disease.”

The sergeant major penned reports of several engagements, including the capture of a Confederate stronghold at Fort DeRussy, La., in March 1864.

Six months later, it was their turn to help defend a fort at Pilot Knob in Missouri against a superior Confederate force.

As Sutton tallied up the opposing sides, “Something over 1,000 men in the fort withstood 14,000 outside,” he wrote. Facing those odds, the Union soldiers abandoned the fort in the middle of the night by way of an unguarded road.

Eventually, Sutton was able to describe an obvious turn in the tide of war.

“Every report that comes from the east tells us of Union successes and Rebel defeats. The emblem of the free will not much longer be trailed in the dust by traitors.”

In a letter to another sister, Mary, he said was looking forward to returning to civilian life. Sutton said that he had applied for a job as a government clerk — certainly a career in keeping with his regimental assignment. However, Sutton’s front-page obituary in The Columbian described him as a painting contractor.

But he didn’t stop writing about the war.

One of the transcribed documents was a letter Sutton wrote in Vancouver on Feb. 28, 1903. It apparently was part of an ongoing correspondence with C.A. Peterson, regarding the role of some Missouri troops in the Battle of Pilot Knob — 39 years after it was fought.

Sutton’s closing comments in his account of Pilot Knob was a tribute to those who fought in the battle. His words also might serve as a salute to a lot of other soldiers who have been part of a lot of conflicts over the years. He wrote:

“None but true soldiers under brave officers, with a patriotic zeal that knows no defeat, are equal to an occasion like this.”

Tom Vogt: 360-735-4558 or tom.vogt@columbian.com.