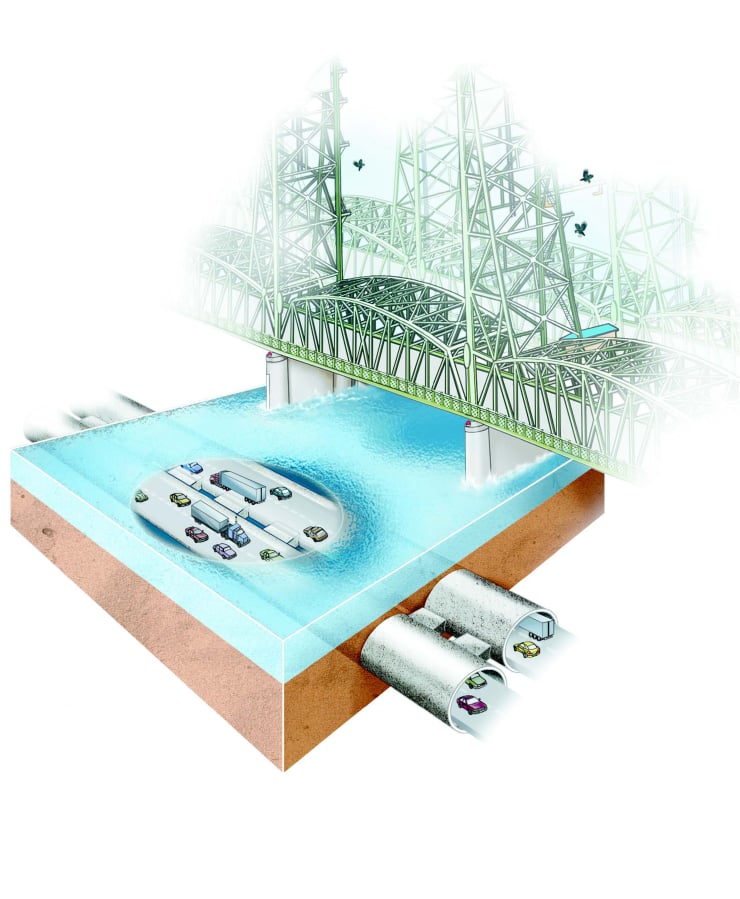

Oregon and Washington lawmakers met for the first time to talk formally about an Interstate 5 Bridge replacement in December. The subject matter was nonspecific and process-oriented, but it at least got them talking, which is something considering the icy relationship between the two states when it comes to the bridge.

Beyond that meeting, the Legislature is still discussing transportation funding, which could include money for crossing-related projects.

Gov. Jay Inslee included $17.5 million in his proposed budget for an office for the I-5 Bridge replacement project. Late last month, Senate Transportation Committee Chair Steve Hobbs, D-Lake Stevens, released a 10-year infrastructure plan that included $3.17 billion for a replacement bridge.

Two other bills, in the House and Senate, would allow the Washington State Department of Transportation to designate qualified projects as being of “statewide significance.” Such projects would get a staff coordinator to help speed up planning, permitting and development.

Vancouver Democrats Sen. Annette Cleveland and Rep. Sharon Wylie are among the bills’ co-sponsors. Both bills were forwarded to their chambers’ rules committees for further consideration.

The House Transportation Committee did not pick up a bill to lay the groundwork toward a third bridge over the Columbia River in Clark County, proposed by Rep. Vicki Kraft, R-Vancouver, leaving that bill essentially dead.

On Wednesday, the Senate Transportation Committee passed a $15 billion transportation funding package that included an additional $450 million toward a new Interstate 5 bridge over the Columbia River. Sen. Annette Cleveland, a Vancouver Democrat who serves on the committee, characterized the money as a down payment toward design and planning, to go with future money from Oregon and the federal government once a solid plan gets going."

— Andy Matarrese