PITTSBURGH — His TV neighborhood, was, of course, a realm of make believe — a child’s-eye view of community summoned into being by an oddly understanding adult, cobbled together from a patchwork of stage sets, model houses and pure, unsullied love.

Visiting it each day, with Mister Rogers as guide, you’d learn certain lessons: Believe you’re special. Regulate your emotions. Have a sense of yourself. Be kind.

And one more. It was always there, always implied: Respect and understand the people and places around you so you can become a contributing, productive member of YOUR neighborhood.

Fred Rogers’ ministry of neighboring is global now, and the Tom Hanks movie only amplifies his ideals. But at home, in Pittsburgh, Mister Rogers moved through real neighborhoods — the landscape of his life, the places he visited to show children what daily life meant.

Once, during one of his programs (he disliked calling it a “show”), he said this: “That’s what loving people is all about — making a safe place to live and move and play and sing.”

In western Pennsylvania, where his actual neighbors were, the ripples he left behind reveal a strong sense of faith — not merely the religious faith that shaped his ideals but a deep, nonsectarian commitment to the impressive, imperfect, always striving patch of the world where he chose to make both his program and his home.

Audience of believers

You believed.

If you were a Pittsburgh kid watching him in his 1970s and 1980s heyday, you believed that his neighborhood was in our midst, and that he was in there somewhere. By extension, you could believe in the neighborhoods around you just a little bit more.

And in words that came from Mister Rogers, from parents, from teachers, from Pittsburgh’s beloved mayor Richard Caliguiri, you could believe this, too: that in a region beleaguered by industrial transition, a hopeful path might be found in the patchwork neighborhoods that dotted western Pennsylvania’s hillsides. Ones that, for so many here, felt like those tiny houses at the beginning of his program.

“To the world at large, he plays the role of a philosopher,” says Bill Peduto, Pittsburgh’s current mayor and a native of this area, who was 3 when “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood” first aired. “But to Pittsburgh, he was a neighbor.”

Why? Partially because Mister Rogers — calling him “Rogers” on second reference seems wrong — deliberately worked to eradicate the magical membrane between television and reality. That was designed to draw in his audience, wherever it was. But for this area’s children, it had the dizzying effect of amplifying the belief in his TV world.

You believed because of the Hotel Saxonburg, the restaurant north of the city where he once popped in to order a cheese sandwich and show viewers how the kitchen worked. You believed because of Wagner’s Market, where they handed him a pricing gun and let him price a few jars — and because he built a toy version of the grocery for his fictional neighborhood and matched up the exterior shots.

You believed because of visits to the Heinz plant on the North Side to see soup made, to the trolley museum to learn about mass transit, to Jewart’s Gymnastics to watch a workout, to Pittsburgh optometrist Bernard “Pepper” Mallinger for an eye exam.

“Fred Rogers recognized the wisdom in everyone: the person next to you on the bus. The baker. The restaurant owner. The recognition that there’s something better about the people next to you,” says Gregg Behr, who runs the Grable Foundation, a Pittsburgh philanthropy aimed at improving children’s lives. He is working on a book about what Mister Rogers can teach kids today.

And you believed because when the little boy from somewhere else asked him, “Mister Rogers, where do you live?” the answer was, thrillingly: “I live in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.”

It was real. He was real — a non-practicing Presbyterian minister from Latrobe, 40 miles east, a town that also gave the world Arnold Palmer and Rolling Rock beer. A guy people saw around town with his wife, Joanne. Who sat in the same pew, four rows from the back, most Sundays at Sixth Presbyterian in the heart of Squirrel Hill, his off-camera neighborhood. Who swam in the Pittsburgh Athletic Association pool.

Who always found the time to talk to the children who couldn’t square the fact that the reassuring man from inside the TV set was suddenly standing right in front of them.

Says Joanne Rogers, now 91: “He got his ideas about community here.”

In this geography of tiny acolytes and their adults, he was not yet the metal statue that now graces the bank of the Ohio River, keeping watch upon the skyline. He was simply someone who found value not only in who they were but in their home itself, a place of possibility even when reality sometimes said otherwise.

“He used Pittsburgh to show the world how the world worked,” says Jeff Suzik, director of the Falk Laboratory School, a progressive school in the city’s Oakland section that one of Mister Rogers’ sons attended — and that teaches to many of his ideals.

“This is a city that makes things,” Suzik says. “Children learn better by doing and making. He knew that. He understood that instinctively. And that mattered here.”

Red cardigans

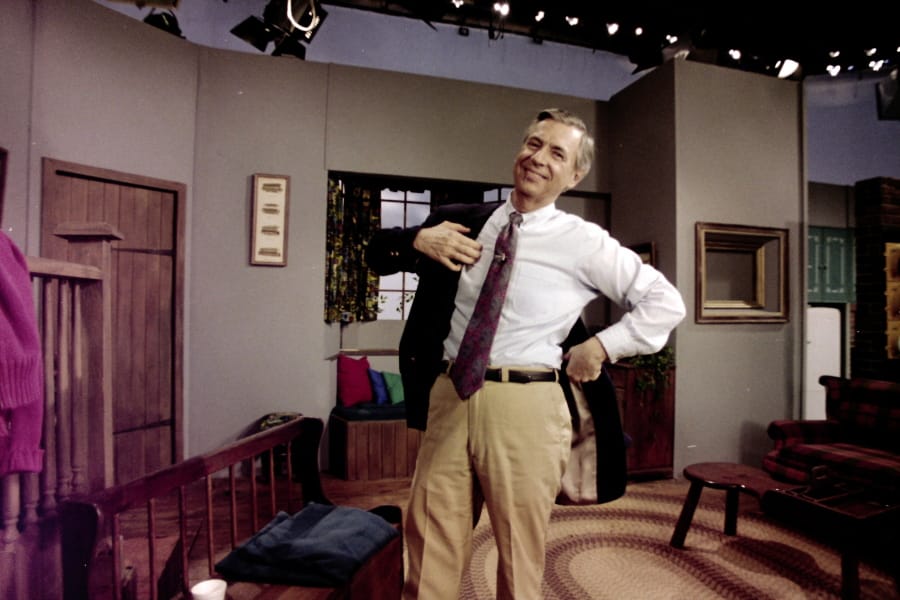

The zippered red cardigans came out in force last week. They showed up on tables at WQED-TV, his old studio, to be donned by visitors for “World Kindness Day.” As the film’s premiere approached, they were zipped onto newborns at UPMC Magee-Women’s Hospital as Joanne Rogers grinned.

Across Pittsburgh, Mister Rogers reverberates in sometimes un-Rogerslike ways. But as obvious as some of them are — cardigan as quasi-religious icon — the true ripples of his work reveal themselves more quietly, percolating beneath the collective consciousness.

Consider Judy Tredway, a fifth-grade teacher in Keystone Oaks, a school district south of the city. After the shootings last year at Tree of Life synagogue, in the neighborhood where Mister Rogers had lived, she attended a vigil in part because “that would be something he would have encouraged.” Sometimes, she invokes his tenets in class.

“We were always seen as a joke — ‘the dirty mills,’ ” says Tredway, a Pittsburgh native. “So it was, ‘Well, we can’t be just that. Look what we have. How bad could Pittsburgh be if we’re bringing the world Fred Rogers?'”

“Pittsburghers of a particular generation feel a responsibility,” she says. “He was one of us, and we have to carry out our end of the bargain.”

“Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood” unfolded at an opportune time not only in the history of modern child development, where his ideas were firmly grounded, but the history of western Pennsylvania and modern Protestantism as well.

In the 1970s and 1980s, the region was pivoting away from a manufacturing-focused economy as the steel industry cracked and the region started hemorrhaging jobs. The service and technology resurgence that now typifies Pittsburgh had yet to take hold.

From the middle of that, Mister Rogers, in his quiet way, elevated the people who made things — and showed children the inner workings of manufacturing in simple, never simplistic ways. It was perfect for any young audience, but particularly apt around here at that moment.

What’s more, it was grounded in what Paula Kane, a professor of religious studies at the University of Pittsburgh, calls “a mid-20th-century Protestant liberalism that made itself accessible — essentially using New Testament principles to give children an ethos to live by.”

“Fred was mitigating some bad circumstances for the region — the sense people had that they weren’t in control of their lives,” Kane says. “Fred was promoting a noncompetitive ethos. I do think, in steel-era Pittsburgh, that the results of a competitive ethos were pretty evident.”