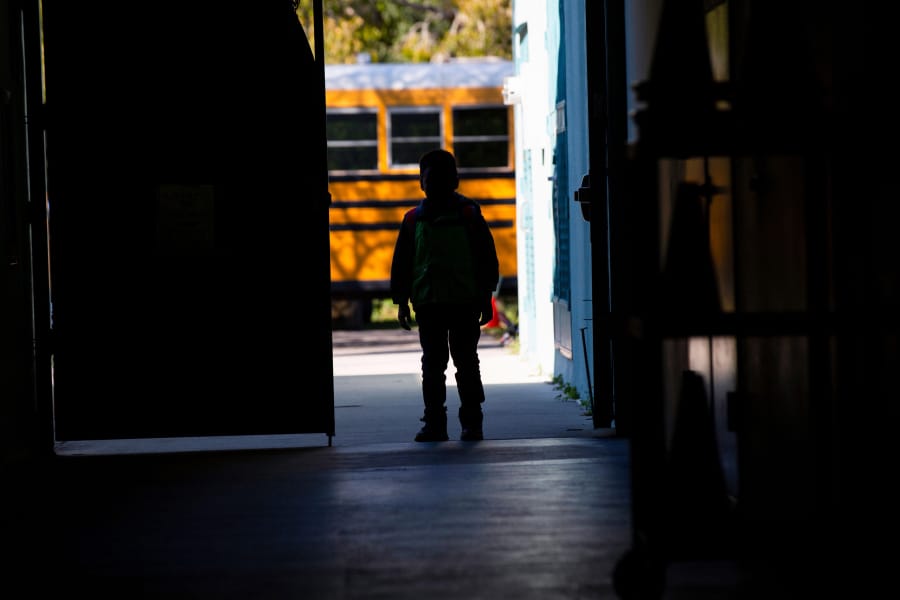

MIAMI — As rooster crows break the silence of dawn, a dozen children march single file down a desolate dirt road and board a bus for school.

There’s not a person or car in sight. Until recently, none of the children had ever held a textbook or scrawled on a chalkboard. Some had never worn shoes. The yellow bus takes off, leaving behind the plastic-sheeted aluminum trailers that until recently had been the kids’ entire world.

It could have been anywhere in rural Guatemala — but it’s actually deep in South Miami-Dade.

Last November a neighbor had spotted the children, barefoot and dirty, chasing a soccer ball during school hours. Her report to a local principal set in motion an unlikely visit from Miami-Dade’s top school administrator. Superintendent Alberto Carvalho was anguished by what he discovered at the secret, squalid migrant camp hidden in plain sight.

“I couldn’t believe what I saw,” Carvalho said. “I mean, my eyes just couldn’t believe what was in front of me.”

In another school district, the discovery of a hidden camp for undocumented migrants might have spelled doom for the camp’s children. But Carvalho, once an undocumented immigrant himself in search of better prospects, did not alert federal authorities, which might have triggered a raid. Instead, he brought shoes and clothing, mattresses, toiletries, even outdoor furniture, and enrolled the kids in school.

“I came to this country at 17 from Portugal. I overstayed my visa,” said Carvalho, who now leads the nation’s fourth-largest school district. “I was poor. I was, in the eyes of some, illegal. I was homeless under the bridge, blocks away from where today I work. … I can relate to them and I really wanted to help.”

He carries the youngest of the bunch, 2-year-old Pedro, during one of his recent visits to a family. He pats the toddler’s back and kisses him on the cheek.

Because of their immigration status, the Miami Herald — which visited the camp and spent two days with the families — has chosen not to disclose the location of the camp or reveal last names.

Most of the children, many of them from impoverished areas of Guatemala, have never owned clean clothes, have never before stepped inside a school.

By day, the kids learn English, math and science, and eat nutritious meals. At night, they and their families sleep in 72-square-foot windowless, ramshackle landscaping trailers. The camp has two communal outhouses and one makeshift shower held together by four slabs of moldy plywood. The migrants cook meals on an outdoor grill donated individually by Carvalho and other school leaders.

The accommodations are rustic at best. The trailers are divided by blankets anchored by string and clothespins, and each person claims a side of the room. But for the 19 families — 46 people in all — that live in the compound, at least there is safety, they say.

The price tag: $275 to $300 each month per person, or around $14,000 per month for the entire camp.

“We all have the same thing in common, so we take care of each other,” said 41-year-old Matthew, who works 14-hour days at a nearby plant nursery. “It’s like a little village.”

There are at least nine other clandestine villages just like it, tucked between sparse nurseries, vast vegetable fields and fruit crops in South Dade, immigration advocates say. Most of them are a combination of abandoned landscaping trailers, dilapidated mobile homes or barrack-style compounds.

Carvalho says he’s tried to visit and make donations to two other camps he learned about from anonymous tipsters at the school district, but the owner of those properties wouldn’t allow him in.

“Unfortunately, the owners weren’t as friendly,” Carvalho said. “Because of that, we haven’t been able to provide the resources we would have liked to.”

Secrecy and security govern the daily routine of the camps, where detection can lead to arrest, detention and deportation. Residents deploy a haphazard system of makeshift locks, lookouts and drills. Youngsters are taught to hide when strangers arrive. And there’s Maria, the unofficial trailer nanny.

By the time the kids wake up, most of the parents have already kissed their sleepy little ones goodbye and have gone to work in the fields.

Maria, 39, knocks on the trailer doors one by one, rounding up the kids.

“Good morning; let’s go, baby,” she says in Spanish.

They line up. It’s still pretty dark out so they squint and some yawn, but they all smile.

On their minds: free breakfast and English class. On Maria’s mind: Making sure the kids don’t get caught.

“Mantenganse alertos,” she tells them. “Stay alert.”

Despite the migrants’ fears of apprehension and deportation by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, Carvalho has vowed to protect the kids — and he is backed by federal law.

The Federal Education Rights and Privacy Act prevents schools from releasing student records to federal authorities, including immigration status, without parental consent except under exceptional circumstances. That’s because a landmark 1982 U.S. Supreme Court decision out of Texas, Plyler v. Doe, ruled that states could not deny free, public education to undocumented children.

“They have a right to an education. But they’re also on the run, living in hiding and they are scared,” Carvalho said. “But we need everyone to understand that Miami-Dade County Public Schools does not, and will not, share information with (ICE). That is a myth that simply just isn’t true.”

But Maria’s fear is still very real.

Historically, ICE and U.S. Customs and Border Patrol have said that they won’t engage in immigration enforcement procedures at schools or places of worship, known as “sensitive zones,” unless there are “exigent circumstances.” According to ICE, this goes beyond classroom hours and extends into aftercare programs and school bus stops when school children are present.

However, it’s not unusual of for undocumented parents to be arrested on school grounds. Earlier this month, immigration authorities arrested a pregnant mother as she dropped off her preschooler in Philadelphia, according to a report on KYW Newsradio.

The arrest came only days after the Trump administration sent agents who normally patrol the southern border to sanctuary cities such as Atlanta, Los Angeles and Houston in the latest escalation of efforts to round up undocumented families.

The Miami Herald spoke with several state and local law enforcement officials, who asked for anonymity, who acknowledged that they know about almost a dozen migrant camps in the region and “look the other way.”

“It’s not our job to do the police work of the federal government,” one officer told the Herald. “But I can understand why they would think we would inform ICE about their whereabouts. Not all cops are the same. Some will do it, others won’t.”

Miami-Dade County school administrators say the school district doesn’t ask about immigration status for student enrollment.

“We just want them in school, learning, doing what kids should be doing, period,” Carvalho said. “Their status doesn’t matter to us.”

The majority of the children at the secret migrant camps are from Guatemala — a reflection of what’s happening at the southern border.

CBP data show a majority of migrants from Central America are fleeing Guatemala, a nation of 17.2 million that borders Mexico to the north. CBP’s report shows the agency arrested more than 185,000 families and 30,000 unaccompanied minors from Guatemala in the budget year ending in 2019.

“We’ve definitely not just seen an increase in the number of migrant children enrolled in our school, but we’ve specifically seen an increase in the number of kids crossing the border from Guatemala,” said the principal at the school the secret migrant children attend.

The number of Guatemalan-born children being enrolled in Miami-Dade schools has more than doubled in the last three years. On Jan. 31 2017, there were 1,110 Guatemalan students enrolled, compared to the 2,184 enrolled as of that same day in 2020. School district officials couldn’t immediately provide general migrant student data as of Feb. 26.

This school year Palm Beach County added more than 4,500 new K-12 students from Guatemala — nearly a 50% jump from the previous two years.

Families, like the ones at the South Dade compound, cite increased violence, poverty and lack of access to schooling as reasons for crossing the border.

The figures back them.

School leaders have taken care of the migrant children as if they were their own.

“When they say ‘it takes a village,’ they weren’t lying,” Carvalho said, referring to how much effort is required to not just educate the youngsters, but also help them become ready for schooling.

That includes an ESOL — English for Speakers of Other Languages — teacher, who teaches the children English, but also doubles as the children’s confidante.

“They tell me everything. Everything about the immigration prisons, about all the walking they did on their journey to the border and how their feet are calloused. They tell me how bad people held them hostage for money.

“Others just want a hug,” the instructor said, noting that there have also been some challenges.

Not all of them speak Spanish, but rather indigenous Mayan languages such as Achi and Mam.

“We rely on their classmates, who know both languages to help translate,” she said. “It’s incredible the improvement we’ve seen.”

The cafeteria director keeps tabs on the kids when they’re in line to get their lunch. Sometimes, they want to take food home to their mom or dad, so she makes sure they eat first.

“They are my precious ones,” she says, dashing from the lunch line, while a youngster sits waiting for his treat. She knows 9-year-old Juan already ate his chicken nuggets and sweet potato wedges. The dessert of the day is a chocolate chip cookie, his favorite.

She keeps a side job each morning at the school clinic — the kids’ first stop.

“It’s like a check-in,” the principal said. “We want to make sure that they’ve showered, don’t have an odor, have clean clothes. If not they’ll be bullied. Kids can be mean.”

At the beginning of the school year, the staff took note of the kids’ shirt, pants and shoe sizes, just in case they need to be replaced.

With a smile, a school staffer grabs an extra-long cotton swab and cleans the inside of 6-year-old Jose’s ear.

He giggles.

She smells his head, and then combs his hair after spraying violet water cologne. She then replaces his tattered sneakers, which are soaked in mud.

His eyes glow, like his new pair of shoes, which light up in neon green with every step.

“Completo!” she said as the boy hugged her leg. “He’s new.”

The principal is known for being friendly — not intimidating.

“Back in my day, people were scared of their school principal,” he said. “But they see me like a friend, like someone they can trust and give a high-five to at the end of the day before boarding the bus back home.”

And so back home they go. The ride is bumpy but the kids are happy.

“I want to be a doctor, what do you want to be?” one girl asks a boy in Spanish.

“A pilot,” he says. Another chimes in: “a photographer.”

And another: “Pokemon!”

Giggles filled the bus as one child asks a Herald reporter if she was Lois Lane from the movie “Superman.”

“Because my dream is to be Superman,” he says in Spanish. The bus arrives at the destination. “My teacher told me that if I do well in school, I can be.”

Like a flood, the kids rush out and wave goodbye to the bus driver. They play tag as they make their way back to the two-acre property of trailers, all arranged in a semi-circle. At the center is a mini-junkyard with rusty landscaping equipment, broken bicycles and large tires.

Within minutes, the children wander back to their homes, take off their backpacks and play soccer in the dirt with a stray black mutt whose name changes every day, depending upon which kids are playing with him.

On that day, his name was Sammy.