Dorothy Smith has always been humble, faithful and fearless, she said. What did she have to fear, with such a powerful calculator between her ears?

Smith, 95, has recently become famous within the corridors of Touchmark, an east Vancouver retirement home, for her Cold War computing work on behalf of the Navy.

Just recently, Touchmark has highlighted interesting female residents in an in-house calendar — and the humble Smith has found herself fending off questions: Didn’t she work for NASA and the space program?

No, she says. As befits a mathematician, Smith likes accuracy. Her friends are thinking of the recent film hit “Hidden Figures,” which revealed how black women using nothing but pencil, paper and their own amazing math skills helped the first Americans reach space in the 1960s.

Smith wasn’t one of them, but she did similar computing work in the 1940s and ’50s for the Naval Research Laboratory in Madison, Wis. Picture a huge room full of women — and just a few men — digging through reams and ribbons of paper, clacking away on huge calculators, testing the theories of scientists developing cutting-edge missile technology.

“We did pretty routine work for several atomic physicists,” Smith said. “It was pretty wild.”

Smith grew up in Oklahoma. Nobody in her family had ever been to college before her brother, who eventually became a doctor. Smith wanted to do the same, and planned to attend medical school alongside her fiancee, Sam, but World War II interrupted their plans.

Sam Smith volunteered for the Air Force and the future Dorothy Smith enrolled in Phillips University, where she studied all the subjects that women weren’t encouraged to try in those days.

“I always loved math,” she said. “I also took astronomy, physics, and biology.”

Her first post-college job was working for the geophysics department at Continental Oil Co. during the war.

“It was a man’s job but there were not too many men around,” she said.

When the war ended and Sam returned, the couple married almost immediately, Smith said. As Sam caught up with his own college education (and did become a doctor), Smith undertook graduate work and taught mathematics at the Universities of Oklahoma and Wisconsin.

In those postwar days her typical students were war veterans and college football players — big, beefy guys who could easily have hassled her with sexist attitudes.

Nothing like that happened, she said.

“They were very respectful. And I was very respectful of them,” she said. “It was a time when the country was very united and doing a lot for the veterans.” Many were attending college for free thanks to the G.I. Bill.

Later, she went to work for the Navy in that big room full of women and calculators, helping crunch the numbers that would underlie what’s called “flame theory” and the development of supersonic ramjet engines used in missile and other weapons technology.

Unlike the suspenseful situations portrayed in “Hidden Figures,” Smith said life in her calculation room was anything but dramatic.

“I made a lot of good friends,” she said.

They found ways to keep one another amused while devoting themselves to advanced calculus, like working out the precise calculations required to make their clacking calculators sound like chugging trains, she said with a laugh.

After her stint with the Navy, Smith went back to doing “more of the things a woman would do.”

Her husband pursued a professional life in the New York area while she raised a family.

Then he was invited to become the first executive director of the M.J. Murdock Charitable Trust, and the family moved to Vancouver.

Smith spent years as a volunteer for many organizations, and she traveled the world with a group called the Friendship Force and with her husband after he retired. He died in 2004.

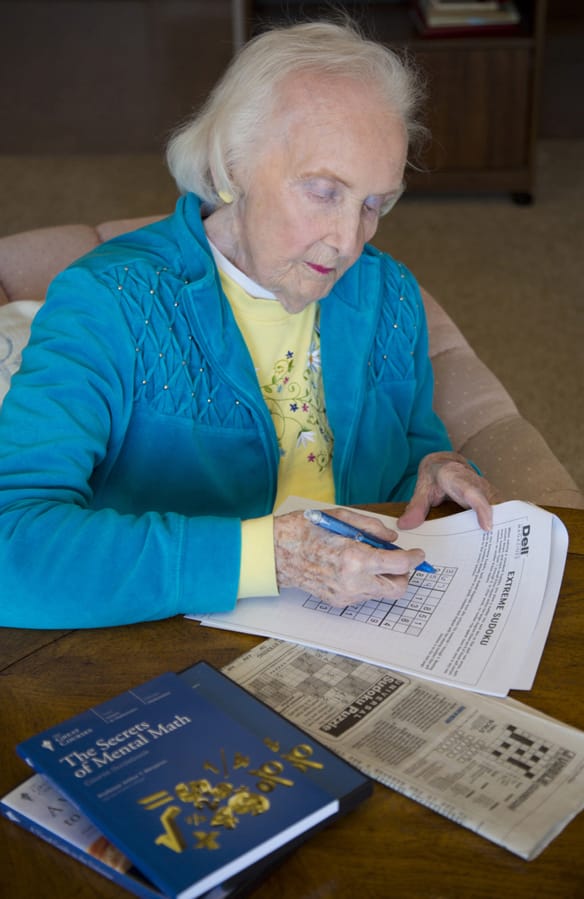

Today, Smith keeps working math puzzles and keeps taking The Great Courses online.

“I am a lifelong learner. I never want to stop,” she said. “Math is in everything. It’s in the waves of the ocean, the patterns of weather. It’s all mathematics.”

While she never felt disrespected, diminished or blocked by men who didn’t take her seriously, Smith acknowledged that sexism was built right into the social structures of her era. That’s why, during this interview with The Columbian, she mentioned doing “men’s work” before withdrawing into the traditional female sphere.

As she told the Touchmark newsletter, her advice to today’s women is: “Just do your best and don’t feel inferior. I never felt inferior.”