PORTLAND – Portland once had a dire reputation in certain circles. Back in the 1950s, the blue-collar town was known as the “abortion capital of the world.”

“Insiders here say Portland is considered wide open so far as abortions are concerned,” San Francisco Chronicle city editor Abe Mellinkoff wrote to Rose City officials in 1951. “There is known to be traffic to Portland by local women unable to get abortions in San Francisco.”

Mellinkoff had heard that girls arriving in Oregon’s largest city had only to discreetly ask taxi drivers or elevator operators where to go.

This was more than two decades before the U.S. Supreme Court made it legal to deliberately terminate a pregnancy. At the time, Portland had a thriving underworld, thanks to on-the-take cops and politicians. Here “the price ranged from $100 for an illegal abortion from a former whorehouse operator in a hotel room to $750 in one practitioner’s plush suite of offices,” offered one report.

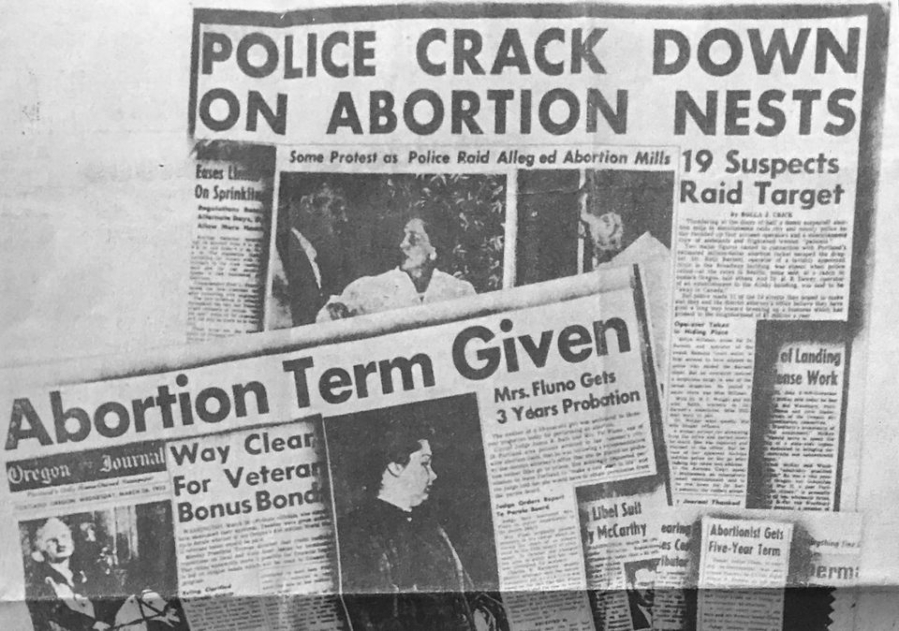

The public’s growing awareness of the local “abortion racket” led The Oregon Journal to take action. The evening newspaper’s editors decided to send reporter Rolla J. “Bud” Crick undercover to find out how it all worked.

Crick quickly confirmed what was already widely believed: that many abortions were carried out in unsanitary conditions by amateur doctors, sometimes even causing patients to collapse in the street on their way home.

The reporter, a Boy Scout leader in his spare time, soon teamed up with law enforcement as he continued his covert investigation, resulting in some pulse-pounding moments.

“I was in this tough joint to meet our contact man, with a policewoman posing as my girlfriend,” Crick later recalled. “We had just made our contact when her purse fell on the floor and her police badge went scooting across the floor. Luckily, she had enough other junk in there to hide the badge while we dived to recover it.”

As it turned out, the undercover operation got even hairier for the policewoman. Pretending to be pregnant and in desperate need of an abortion, she found herself getting drowsy in a makeshift operating room.

“She was supposed to run to the window and blow her whistle for the pinch once [the abortionist stepped into the room],” Crick said. “But the pill they gave her made her so complacent she could hardly muster strength enough to whistle.”

Crick, a combat reporter for the Army Air Corps during World War II, enjoyed the cloak-and-dagger experience, and so he became the Journal’s Nellie Bly. He’d follow his undercover assignment on the abortion beat with one at the Oregon State Hospital in Salem. There, posing as an attendant, he “helped administer electric shock treatments to patients” and “saw the dramatic results of the newest ‘mind’ drugs.”

More than half a dozen years before Ken Kesey published his novel “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” which is set at an unnamed Oregon state institution, Crick found Oregon State Hospital’s cast of characters fascinating.

“The mental condition of one man who had participated in a daring and sensational Oregon train robbery years before had deteriorated to the point that he was catatonic and merely sat looking at the floor,” Crick recalled years later. “Another patient who had gone on an arson spree in Portland neighborhoods turned out to be one of my former Boy Scouts. Apparently, I taught him too well how to make fires.”

The movie version of “Cuckoo’s Nest,” starring Jack Nicholson, would be filmed at Oregon State Hospital.

But Crick’s expos’e of the state psychiatric hospital didn’t have the immediate impact of his “abortion racket” articles, which shocked readers and resulted in an NBC TV adaptation called “The Helpless Ones.” (The actor Dennis Patrick, later known for roles on “Dark Shadows” and “Dallas,” played Crick.) In the wake of Crick’s initial reporting, law enforcement raided a series of “abortion mills” around Portland, with the Journal writing that “police and sheriff’s deputies thundered at the doors of suspected abortionists to round up operators, assistants and frightened patients.”

The resulting arrests brought multiple convictions, most notably of Dr. Ruth Barnett, a high-profile advocate for safe and legal abortion. Barnett, who operated out of a swanky downtown Portland clinic, would claim in her 1969 autobiography that she had performed thousands of abortions. “In spite of my patients’ tears and anguish, I toiled in a happy climate,” she wrote, “because here, in my surgery, came the end of tears and anguish.”

Crick acknowledged that Barnett was a professional and unconnected to Portland gangsters.

“Of all the abortionists in town at that time, she was the best,” Crick would say.

Three decades after its series of articles about the “abortion racket,” The Oregon Journal noted how times and mores had changed.

“Today,” the paper wrote in 1982, “anyone who desires can walk into an abortion clinic, a doctor’s office, a hospital or to organizations like Planned Parenthood and talk openly about the subject. Then it was a matter of seeking out underworld sources or people who knew someone who performed abortions.”