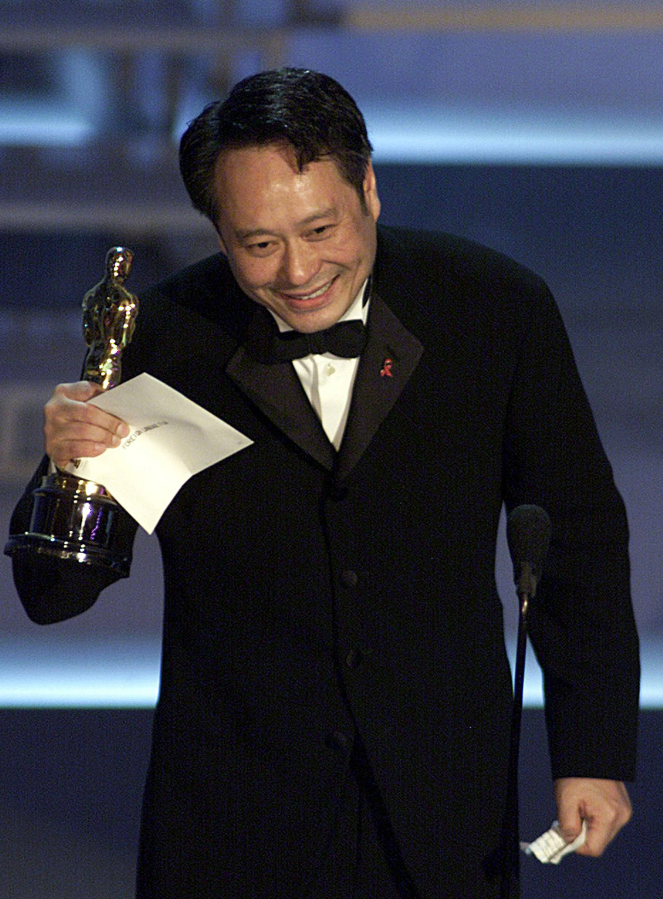

A month ahead of a 93rd Oscars ceremony that promises to be different from any Oscars ceremony in memory, we look back at the one that took place 20 years earlier. On March 25, 2001, three muscular dramas split most of the top prizes: Ang Lee’s “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon” won four Oscars (including foreign language film), double nominee Steven Soderbergh was a surprise winner in the directing category for “Traffic,” and in the best picture race Ridley Scott’s “Gladiator” was the last movie standing.

Los Angeles Times columnist Glenn Whipp and critic Justin Chang sat down to discuss how well those choices have aged and what they tell us about a motion picture academy that was just starting to mirror the growing internationalism of the movie industry.

CHANG: If I recall correctly, Glenn, no one was terribly surprised by “Gladiator’s” Oscar-night triumph 20 years ago, even though it was hardly a preordained outcome, statistically speaking. Going into the night, Scott’s stirring epic of ancient Rome had already won the top prize from the Producers Guild of America, which often bodes well for a best picture Oscar win. But it faced robust competition in the form of two very different critics’ darlings. “Traffic,” Steven Soderbergh’s jagged, Altman-esque deconstruction of the illegal drug trade, had won the Screen Actors Guild prize for best ensemble. And the Directors Guild of America gave its top honors to Ang Lee for “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon,” the Mandarin-language martial arts drama that had become an international sensation.

There were two other nominees (this was years before the academy expanded its top category to as many as 10 nominees). I remain fond of “Erin Brockovich,” that year’s other Soderbergh-directed drama (and the better of the two in my heretical opinion), and not at all fond of “Chocolat,” a fudge-stained relic of an era when Harvey Weinstein could muscle any film into the Oscar race (and, as we now know, was using his industry clout as cover for his serial crimes against women). Of course, there were many other worthier alternatives: beautifully handcrafted films like “Almost Famous” (which earned director Cameron Crowe an Oscar for writing) and Kenneth Lonergan’s debut feature, “You Can Count on Me”; thoughtful, literate dramas like “The House of Mirth,” Terence Davies’ adaptation of Edith Wharton’s novel, and “Wonder Boys,” based on Michael Chabon’s novel; and remarkable films from overseas as different as Edward Yang’s “Yi Yi,” Claire Denis’ “Beau Travail,” Abbas Kiarostami’s “The Wind Will Carry Us” and, of course, Lars von Trier’s furiously divisive “Dancer in the Dark.”