VIRGINIA BEACH, Va. — Along the downtown Hampton waterfront, behind the NASA Langley Visitor Center, you may have noticed the seafood business bustling.

Trucks drive in and out to pick up fish orders from Amory Seafood Co. A fish-shaped sign hangs off the wholesaler’s building, as boats pull up out front.

But in an unassuming brick building next door, Virginia Tech researchers are working on a new means of getting seafood to your table: from a lab.

The group is hoping to figure out the best, most sustainable way to program cells to mimic the look, feel and flavor of the meat we eat.

“Overall we are trying to produce meat without killing animals,” said Reza Ovissipour, a food science assistant professor and lead of the university’s Future Foods Lab and Cellular Agriculture Initiative. “Because of many issues that we have, we need to find other alternative ways to produce meat. This is another way.”

His team was one of six institutions recently awarded a $10 million grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture — marking the agency’s first investment in the lab-grown meat field. Together, the consortium also plans to create a National Institute for Cellular Agriculture.

Food produced from cells could be ready for market in “the not too distant future,” the U.S. Food & Drug Administration said last year. The FDA already has outlined how it will jointly oversee the industry with the agriculture department’s Food Safety and Inspection Service, from cell growth to harvest.

The goal is not to upend or replace existing industries, Ovissipour emphasized. Rather, products made from cells would be one more option alongside traditional steaks or fillets.

Food production will need to rise significantly over the coming decades to meet an increasing global population, he said. Lab-grown items could help, in addition to reducing energy needed and greenhouse gases associated with the meat industry. But actually offering a product is a long way off. The Hampton team, which will get $3.2 million of the grant, is focused on improving the methods that could get us there.

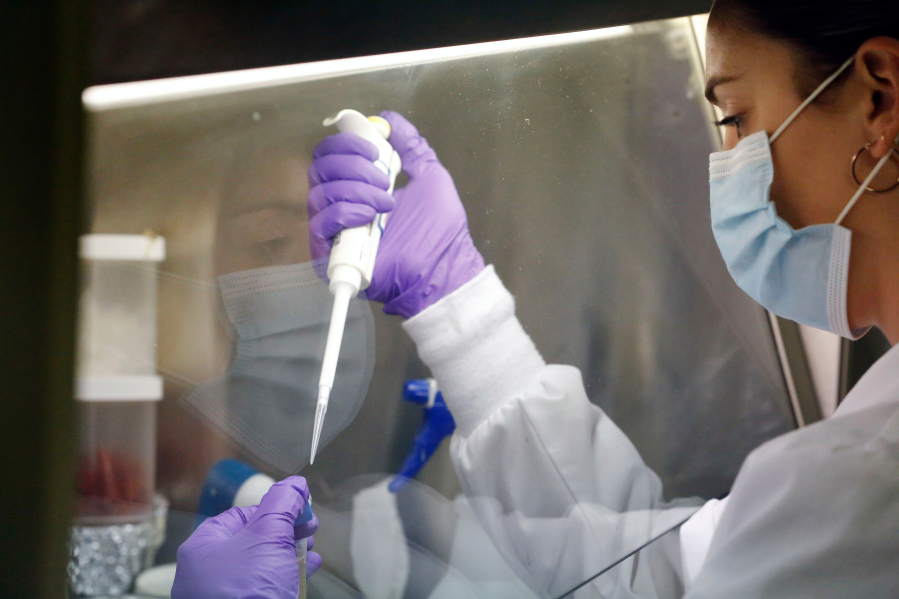

On an afternoon early last week, research technician Rose Thai opened an incubator set to 28 degrees Celsius — 82.4 Fahrenheit.

She pulled out a clear tray divided into compartments filled with pink liquid that houses zebrafish cells. Thai slid the tray onto a microscope, bringing into focus on the corresponding computer screen what looks like little fragments of string bunched together, some floating in between.

The researchers do this nearly every day to monitor how the cells are growing, said postdoctoral researcher Lexi Duscher.

They work out of the Virginia Seafood Agricultural Research and Extension Center on South King Street. The current squat, brick building has been there since the 1950s, but will soon be torn down to make way for a $9 million new research facility. The new building, expected to complete construction within months, will allow for expanded lab capabilities, including bioprinters — 3D printers for biological material such as tissue.

Growing meat in a lab is not new. Scientists and companies have been working on it for years. But the process can be extremely expensive, and the product doesn’t yet match the real thing. It’s different from a GMO, which is an organism whose genes have been altered for a certain purpose, such as crops engineered to resist disease.

Here’s how cellular agriculture works:

Lab workers first isolate cells from various animals, figuring out which correspond with fats or muscles. They then grow the cells using “big kettles” similar to fermenters in the beer industry, Ovissipour said. The idea is those cells could then be “harvested” to make products, he said.

In order to grow, though, the live cells need food — vitamins, proteins, amino acids and so on spun together in a liquid broth. That food is called the growth media, and is the part of the process Ovissipour’s team is focused on improving.

The media traditionally uses a serum derived from cows, which is expensive and negates the concept of a fully animal-free product.

“We don’t want to use that for this process,” he said. “It’s not viable economically and also ethically, it’s not possible.”

His team is working to remove the serum from the process, replacing it with something plant-based. He said they’re using machine learning to help design possible formulations without compromising cell growth.

The Hampton group is focused on seafood.

Duscher said the team uses zebrafish cells because they are well established in the research world. In general, fish are studied less than mammals, she said, making it difficult sometimes to apply the same methods. Eventually they’ll try others, too — including rainbow trout.

Some test fish likely will come from the school’s own aquaculture lab one door over. The researchers biopsy the fish and work to establish a cell line that can be infinitely reproduced.

Eventually, they’ll recruit taste testers to sample lab-grown crab, for instance, alongside the real thing.

The team plans to share what they find with industry partners along the way. Ovissipour declined to name them, but said his focus is on developing the science. Once they get interesting results, companies can take over with actual production.

Another part of the grant will go toward developing training programs for the “next generation” of cellular agriculture scientists, he added.

Duscher said she’s thrilled to be working to solve “real world problems.” Basic science is incredibly important, but you don’t always know how it will end up impacting people, she said.

“This is really exciting because it’s the first time I’m working on something that can be directly applied to something sold, and eaten.”