The chicken nuggets come with a side of Pacific Northwest breeze at Hazel Valley Elementary School in Burien.

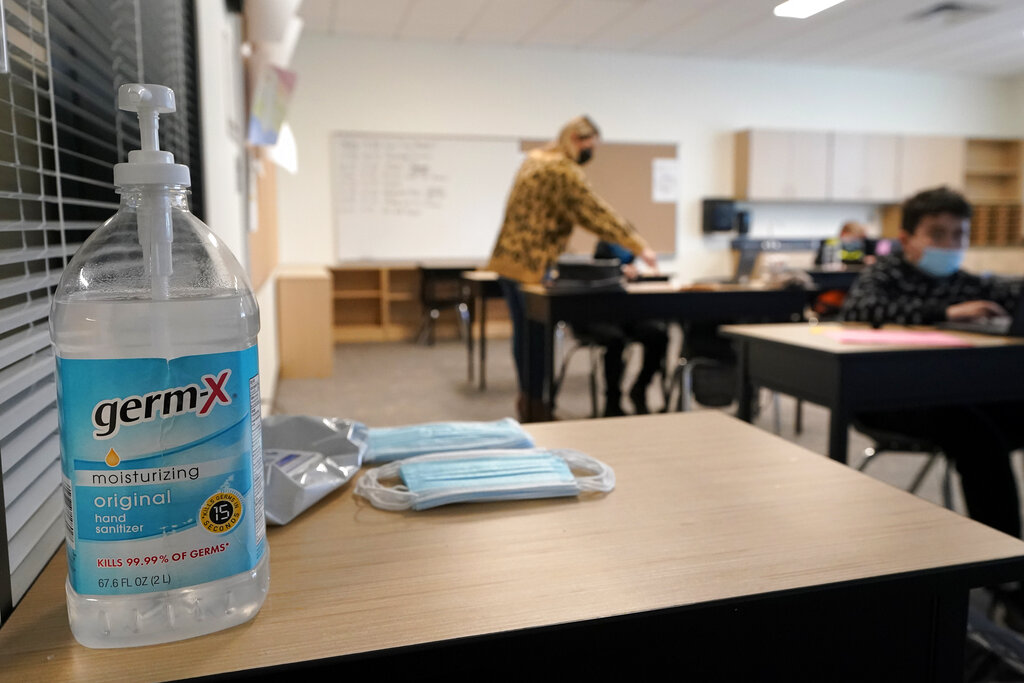

In an unmistakably pandemic scene last week, the external doors to the school cafeteria were propped open during lunchtime. Inside, children sat 6 feet apart at tables. Just outside, kids favoring a meal outdoors sat on opposite sides of repurposed computer tables under a large white tent, several clutching a new style of fidget toy under their tables.

It’s Anaid Villa’s first day supervising lunch and her second day as a paraeducator for Hazel Valley — one of the jobs in highest demand at schools these days, which over the course of the pandemic have posted a record number of open jobs. She walks between the tables indoors, greeting kids in Spanish and opening snack baggies on their trays.

Her boss, principal Casey Jeannot, says the transition to a full school reopening this fall has been difficult, but they’ve managed to keep daily basics, like food service and transportation, running relatively smoothly. The school hasn’t had a single confirmed case of the virus yet.

That’s not the case everywhere.

Since the school year began in-person across Washington state a month ago, the nonacademic aspects are now the factor in flux in many schools as the nationwide demand for labor hits the education world.

A shortage of drivers with commercial licenses has delayed bulk shipments of food, forcing some school districts, such as Edmonds, to serve only cold lunches.

School bus drivers are in short supply across the state, prompting cuts in services and causing delays to routes. In an email sent to parents Friday, Seattle Public Schools warned that the district may lose as many as 100 drivers this month, in part because of the COVID-19 vaccine mandate, and “may only be able to cover one third of the general education routes we currently run. If that is the case, we will not be able to provide transportation to the majority of our general education routes while we implement other strategies.”

Custodians, in higher demand because of increased cleaning protocols, are working overtime. A mild cold can get a child sent home and districts are searching for more nurses. And resignations over the vaccine mandate for K-12 employees is weighing heavy on recruiters’ minds as the Oct. 18 deadline approaches.

“It’s a million little things,” said Chris Fischer, a history and special education teacher in the Kennewick School District.

At Hazel Valley, where it used to take just one person to supervise mealtime, lunch now requires the watchful eye of at least two other adults, Jeannot said. Jeannot, a dedicated parent volunteer, and another paraeducator stood watch with Villa on Friday, reminding kids to keep their masks up and asking those who were hunched over if they needed to grab their coats.

Making this and the other components of the school run smoothly and safely this past month required tinkering with her staff’s schedules and a base of parent volunteers.

The source of the labor shortage in schools is multifaceted. Some education experts, such as Chad Aldeman from Georgetown University’s Edunomics Lab, point to the new COVID-specific roles created in schools and “unfilled positions” during building closures as the source of what districts are calling a shortage.

In other cases, the pandemic made existing shortages, such as bus drivers, even worse.

Fischer, the Kennewick teacher, and others say filling in for missing staffers — a problem made more pronounced by the extra duties of preventing and addressing virus spread — have taken up a lot of energy during the first month of school.

He felt the pressure just this week. During a class period he normally shared with a paraeducator, he couldn’t focus his full attention on assisting a student with an emotional disability.

“I would say the common feeling is that everybody feels behind,” said Matthew Legacki, a special-education teacher at Roxhill Elementary School in Seattle. “Like we’re not getting into the grooves and the rhythms because our attention is taken up by making sure protocols are followed.”

At the same time, virus cases and quarantines in schools sometimes force entire classrooms, schools or programs to go remote. Around 15 classrooms have been quarantined in Seattle; Eatonville Middle School in Pierce County switched to remote learning last month, and other school closures have emerged in the McCleary and Kittitas school districts.

Food shortages

At Hazel Valley and in Highline, Jeannot said, schools have been able to skirt the worst of a food shortage because they decide menus week by week.

But a new national free lunch program, lagging shipments of food and a lack of school food service workers have forced districts to improvise meal items at the last minute or rely on prepackaged food.

Without enough food service workers, schools can’t prepare many hot meals. The supply issues run from top to bottom, said Leanne Eko, who directs nutrition services for the state education department, or Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction. Around 90% of school districts rely on a food distributor, U.S. Foods, which hasn’t been able to fill orders because of driver shortages and coronavirus outbreaks at factories that produce the food products.

Schools also are dealing with a large uptick in demand for school lunches, Eko said. The Biden administration extended a universal free lunch program, started during building closures, through June 2022.

At Madison Middle School in Seattle, parent Reid Raykovich says her 11-year-old daughter — who is deathly allergic to peanuts — was offered one of the peanut butter and jelly sandwiches the school prepared in a pinch last month. Her daughter, who refused the sandwich, sent her a text after it happened, and a friend who works at the school confirmed it.

In an apology over email to Raykovich, the district’s head of nutrition services said a substitute kitchen manager on duty that day failed to seek approval from her supervisor before serving the sandwiches as a backup meal. The school had leftover peanut butter on hand from a donation made by a community based organization, his email said.

Peanuts are not typically served in SPS schools, a district spokesperson said Friday.

Parents and staff also reported schools borrowing food from each other when supplies ran out. Some principals are requesting that students who already brought lunches refrain from taking one from the school’s supply.

Fred Podesta, who leads operations for Seattle Public Schools, said schools have had a harder time anticipating demand for lunches, and sometimes popular menu items run out. He said he wasn’t aware of any school completely running out of food.

Transportation woes

Washington state school districts are responding to a bus driver shortage by cutting services or allowing long delays for bus routes.

In Seattle, dozens of school-bus routes are late every day as drivers run multiple routes, and the vaccine mandate may worsen matters.

As of last week, the district was short about 62 bus drivers, Podesta said on Wednesday. On Friday, Nearly 68 buses were late by up to two hours in the morning and afternoon.

Of the nearly 100 open positions in Edmonds school district, the most acute employee shortage has been bus drivers, said Harmony Weinberg, a district spokesperson. At the Kennewick School District, bus drivers are no longer transporting students for sporting events.

The problem is especially challenging for students with disabilities. Sometimes buses will arrive without a wheelchair lift or aide to help her daughter, parent Lauren Soini said.

At Roxhill in Seattle, Legacki said, the principal — along with another staff member — sometimes drives students home herself because the delays are so long.

Relief in the return

Despite the kinks, some families are still celebrating what the past month of school has meant.

At Seattle’s Ingraham High School, the halls are full of students and some classrooms have more than 30 kids. But there are still no in-person pep assemblies, just recordings to watch of individuals and smaller groups celebrating school spirit, student Maggie Cahill said.

But Maggie, a senior, said she didn’t realize “the little things I took for granted,” like in-person conversations and being able to make eye contact with people.

In Cristin Gordon-Maclean’s family, Friday evenings are for pizza. But on Oct. 1, the slices “felt especially celebratory,” she said. Cristin and her husband, Andy, raised their glasses to toast a full month back in school with in-person instruction.

Gordon-Maclean watched her toddler thrive in Hutch Kids Child Care Center, which never shut down, while her older son, Elliott, struggled to finish kindergarten and first grade via an iPad screen.

Elliott seems happier and less anxious these days, she said. And the new administration at Pathfinder K-8 school in Seattle has held multiple listening sessions with families and created a welcoming and safe school environment. There have been three reported cases of COVID-19 detected at the school during its first month open.

“Our son is exactly where he needs to be — in school with his teacher and peers,” she said.