TACOMA — It didn’t take long for Sugar Ray Seales to produce the Olympic gold medal that put him — and Tacoma — on the map back in 1972.

As we walked down the wooden stairs at Shiloh Baptist Church on Hilltop, not far from the house on South 25th and G Street where he once lived, Seales pulled it from his front pocket, seeming to know instinctively that when he handed it to me, warm, heavy and worn from years of being shared, it would stop me in my tracks.

“That’s my American Express card,” Seales told me as he slowly unspooled the gold chain that holds the medal, perhaps not realizing that I already knew his next line — because he’s used it on just about every journalist that’s come his way since he won gold in Munich 50 years ago.

“I never leave home without it.”

It’s an unquestionably great quote from a legendary boxer who’s offered plenty of them over the years. But the thing is, Seales — 70 and legally blind, one of many lasting effects of the violent sport that made him famous — doesn’t have a home these days.

For the last three weeks, he’s been sleeping on the bottom bunk of a bed in Shiloh Baptist’s basement, where the church hosts its shelter for single men, he told me.

Seales decided to make his way back to Tacoma in November, not long after the death of his wife of more than 30 years. Traveling with a stepson, he left Indianapolis, where the couple had long lived, for the place where he first made a name for himself, he said.

What he didn’t realize was how hard it would be to find a place to live once he got back home, he admitted Wednesday. Any money he made during his career is long gone, and the impact of some 350 amateur fights and nearly 70 as a pro have left their mark. All he’s ever been is Sugar Ray Seales.

“It’s not supposed to be like this,” Seales said, his pummeled hands, still like bricks, holding the medal firm. “I expected a room or a place, you know? Because I took care of Tacoma. … I had so many friends here.”

In 1972, when Seales returned from the Munich Olympics, a helicopter flew him to Cheney Stadium, where a crowd of 5,000 celebrated the young champion.

Five decades later, with the same medal in his pocket, he says he’s just hoping to catch a break.

‘Not so glamorous’

Seales, who moved to Hilltop from the Virgin Islands when he was 12, was the first in a string of local boxers to bring glory in the ring to a hardscrabble city, emerging from the famed Tacoma Boys Club, and the tutelage of legendary coach Joe Clough.

In 1975, two-time Olympian Davey Armstrong won a gold medal at the 1975 Pan-Am Games, and a year later, Leo Randolph took home Olympic gold in Montreal.

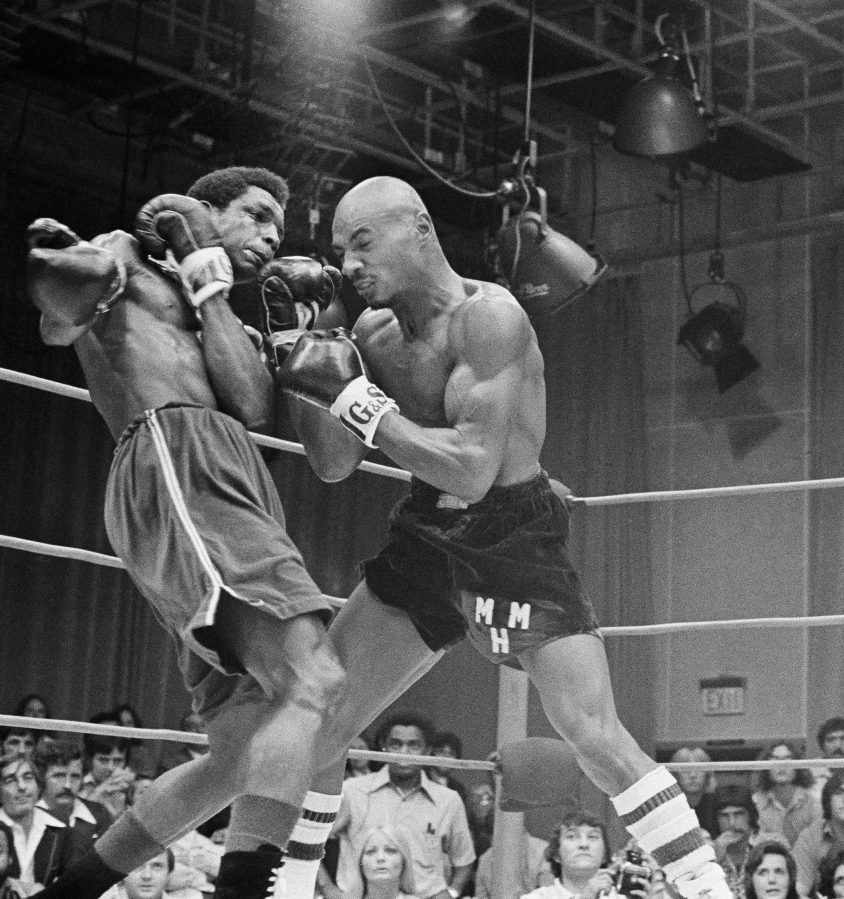

As an amateur, Seales notched more than 300 wins, with 200 knockouts. Across the decade-long professional career that followed, including multiple bouts with future middleweight champion Marvin Hagler — who Seales battled to a draw in Seattle in 1974 — he amassed a 56-8-3 mark.

“It was a party. It was a big celebration,” Seales said of his life in the immediate aftermath of the Olympics. “I’d done something. I’d done the best thing I could do for America.”

At the same time, the sport that Seales loved hasn’t always returned the favor, sometimes by cruel fate, and at other times by sheer brutality. His 1972 victory in Munich — where he became the only American boxer to win gold — was overshadowed by the murder of 11 Israelis by terrorists affiliated with a Palestinian militant group. Meanwhile, injuries sustained toward the end of his professional career left him blind in both eyes, and wracked with medical bills.

A 1984 benefit held at the Tacoma Dome, which included a performance by Sammy Davis Jr. and an appearance by Muhammad Ali, helped bring his accounts current, according to The News Tribune archives. But more recently, as the Indianapolis Star reported in 2018, Seales was living “flat broke,” bumming rides to a “dark and dingy” gym, where he spent his time coaching upstart fighters.

Former News Tribune sport columnist John McGrath interviewed Seales during more than two decades at the paper.

This week, McGrath said that speaking with Seales long after his retirement from professional boxing was always a stark reminder of why boxing was once a premier sporting event in the U.S., and also the toll it took on young fighters like Seales, including many Black boxers who sought to escape poverty through their exploits in the ring.

“There’s nothing like it. It’s fabulous. It gets your heartbeat up, and your pulse just going. It’s absolutely incredible, and yet, it seems like, for so many people … it leaves them in bad shape,” McGrath said, noting that boxers from Seales’ era didn’t earn anywhere near the financial paydays that those who followed in their footsteps enjoyed.

“I kind of sympathized with him,” McGrath said.

“Every time I hear a name like Ray Seales, those two worlds kind of converge — the part that’s glamorous, and the part that’s not so glamorous.”

Cheap hotel rooms

For all the storybook highs and the humbling lows he’s encountered over 70 years, Seales still can’t help but shake his head when he stops to reflect on the latest chapter of his remarkable life.

He never expected to be back in Tacoma, he says — at least not like this.

After arriving in November, Seales said he spent nearly four months renting cheap hotel rooms, mostly along South Hosmer Street, quickly exhausting his monthly social security disbursement at a rate of $80 per night.

But just as his money was drying up, Shiloh Baptist Pastor Gregory Christopher appeared, Seales said, having learned of the boxer’s plight from friends and family.

From his office Wednesday morning, Christopher — who first met Seales roughly 20 years ago — said he offered Seales a private room in the basement, at least until he can get off the ropes, describing the decision as “a no-brainer.”

Gregory is hoping to help the gold medal winner find an apartment he can afford, he said, and praying it happens sooner rather than later.

“I wasn’t good with that. I wasn’t good with that at all,” Christopher said of his reaction to learning that Seales was living in hotels on Hosmer Street. “It was a little personal for me … so I had to help him.”

Sitting nearby, Seales stressed that he isn’t mad about his current situation. He’s grateful he has a place to stay, he told me, and spends his days trying to help the other men at the shelter — relying on his experience as a former special education teacher at Lincoln High School.

Often, he said, he draws on something Ali told him before he died: “Service to others is the rent we pay for our room in heaven.”

Mostly, Seales said, he believes God has a plan for him.

He fought for Tacoma. He won for Tacoma.

Now he’s looking for one more victory.

“I don’t need a big mansion, or a big house,” Seales said.

“I just need a place to stay.”