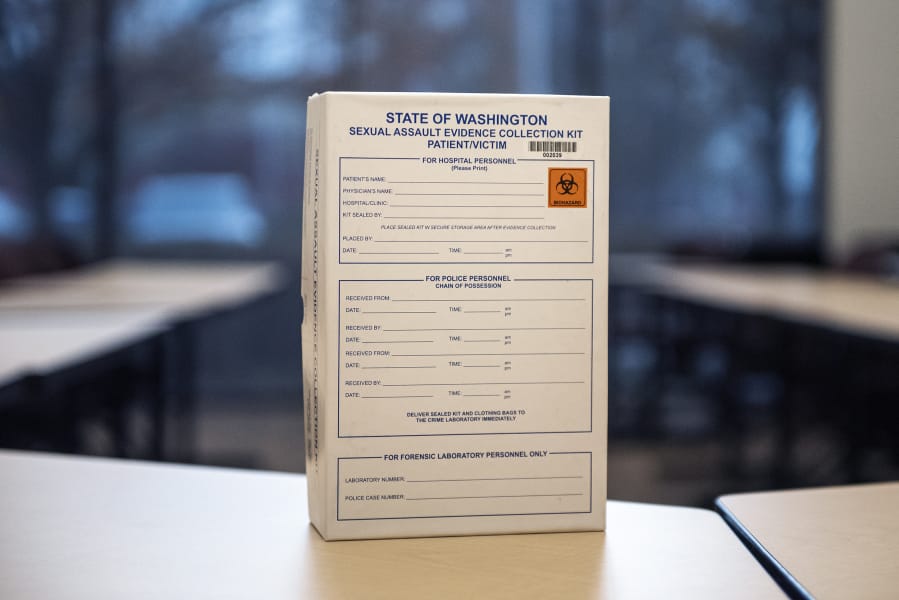

OLYMPIA — At-home sexual assault kits let people collect potential DNA evidence themselves instead of seeking an exam in a medical setting. But the results of a self-administered sexual assault examination have rarely, if ever, been used in a U.S. court case.

Washington lawmakers are considering House Bill 1564, a bipartisan bill that would prohibit the sale of over-the-counter sexual assault kits out of concern they offer false hope and can thwart investigations and prosecutions.

In Washington and around the country, sexual assault advocates, victims, nurses, prosecuting attorneys and police have raised concerns about evidence gathered with such kits not being admissible in court.

“I just don’t think people should profit on trauma,” said state Rep. Gina Mosbrucker, R-Goldendale, one of the bill sponsors. “I think that their heart was probably in the right place in the beginning … but at the end of the day, it’s my job as a legislator to protect people in the state.”

New York-based Leda Health, the only company known to offer at-home kits in Washington, defended its product in a hearing on the bill last week.

Attorney General Bob Ferguson last year issued a cease-and-desist letter requiring Leda Health to stop distributing its kits, following an investigation by The Daily of the University of Washington into a partnership between Leda Health and UW sorority Kappa Delta, through which kits were made available to sorority members.

The sorority chapter declined to comment on the partnership. University spokesperson Victor Balta said the school was not involved in connecting the company with the sorority.

In the letter, Ferguson’s office said the kits violate the state Consumer Protection Act, which bans unfair or deceptive practices. The letter quotes Leda Health’s website, which at the time said “[we] believe though that courts should admit our kit results, especially if all our protocols are followed.” As of Monday, the terms and conditions on the company site said its products and information are not substitutes for professional medical or legal advice, and the company “cannot guarantee” evidence collected will be admitted in court.

The letter also said the office is investigating the company’s marketing, sales and distribution.

King County Senior Deputy Prosecuting Attorney Emily Petersen said her main concern is the kits are being advertised as a way to collect evidence.

“The last thing we want is for a victim or survivor to decide to report a rape or a sexual assault, and only to find out that the evidence that they collected, stored and that they relied on to be admissible is not in fact, admissible,” Petersen said.

Petersen said self-administered sexual assault exams create more questions in court, including how the evidence was collected, who else had access to it and what happened to the evidence after.

Information from at-home kits cannot be uploaded to CODIS, the federal DNA database that tracks DNA samples of those convicted of felonies, including sexual assault and rape.

In a public hearing for the bill last week, Leda Health Chief Strategy Officer Ilana Turko stressed the company does not sell directly to individuals. She said it sells to institutions like governments, universities or sororities. Kit prices are not publicly available.

Along with the kits, the company has a mobile app with video and live chat support, a 24/7 support care team as well as emergency contraception and testing for sexually transmitted infections.

Turko said one purpose of the kits is to “preserve and memorialize somebody’s experience.” She said she is a survivor herself, and spent years blaming herself for what happened.

New York issued a cease-and-desist letter in 2019 to two companies selling at-home kits, Preserve Group and #MeToo Kits Company, which would later become Leda Health. The letter said the companies were misleading consumers by saying evidence collected with these kits could be used in court. States including Michigan, Oklahoma, Delaware, Hawaii, New Mexico, North Carolina and Virginia, as well as Washington, D.C., have issued warnings against buying any at-home sexual assault kits.

Legislation similar to Washington’s bill to ban these kits stalled last year in Utah.

In an interview, Leda co-founder and Chief Technology Officer Liesel Vaidya said the kits provide an option for people in rural areas and those who do not want to go to a hospital for an exam.

Laura Lurry, director of advocacy services at the King County Sexual Assault Resource Center, said victims may avoid seeking care after an assault because they are processing trauma, they may not want to be touched or they fear setting off a police investigation.

But Lurry stressed that exams in a medical setting after a sexual assault can provide more than just evidence collection, and include physical and psychological trauma treatment.

“No one has to do this by themselves. No one has to have a sexual assault exam done by themselves, because there are experts, specialists, sexual assault nurse examiners that are available to help someone through this process,” she said.

Sexual assault nurse examiners can also prescribe medication and offer follow-up care for free in Washington. Exams are paid for by the state Department of Labor & Industries.

The nurse examiners across Washington are trained in evidence gathering, trauma responses and testifying in court. The Legislature unanimously passed a bill last year to bring more SANEs to rural and underserved communities.

Unless the person seeking an exam files a police report, getting a SANE exam does not trigger an investigation.

Leah Griffin serves on the state’s Sexual Assault Forensic Examination Best Practices Advisory Group that has been supporting legislation surrounding sexual assault examinations since 2015.

Griffin said she began this work after she was raped and then turned away from a hospital that did not provide sexual assault exams.

“What I didn’t do is seek out $10 million of venture capital to develop a product to sell to survivors that at its core deceives them into thinking that this is a viable path towards accountability,” Griffin said.

James McMahan, policy director with the Washington Association of Sheriffs & Police Chiefs, said in a hearing that there is no good reason to make sexual assault survivors pay and unknowingly thwart justice.

“It is not their responsibility to preserve the rights of crime victims in our state. It’s ours, it’s yours. This is an opportunity, an obligation quite frankly, for you all to retain that and live up to that responsibility to protect the rights of crime victims in our state by passing this bill,” McMahan said.

A House committee is set to vote Tuesday at the earliest. Mosbrucker hopes that similar legislation will be taken to the congressional level.