When the Columbia River Economic Development Council was formed in 1982, the three largest employers in Clark County were the Boise Cascade paper mill downtown, the Alcoa aluminum smelter near the Port of Vancouver and the Crown Zellerbach paper mill in Camas.

“It was a very blue-collar and smokestack economy,” said Joe Tanner, who served as the council’s first president from 1983 to 1989.

“Our job was to diversify,” said Tanner. “And I think we did.”

Today, Clark County is home to a thriving ecosystem of high-tech industry, an industry that is looking to expand even more in the region. The question remains: What will make it grow?

Enlarge

Amanda Cowan of The Columbian

Pioneering companies

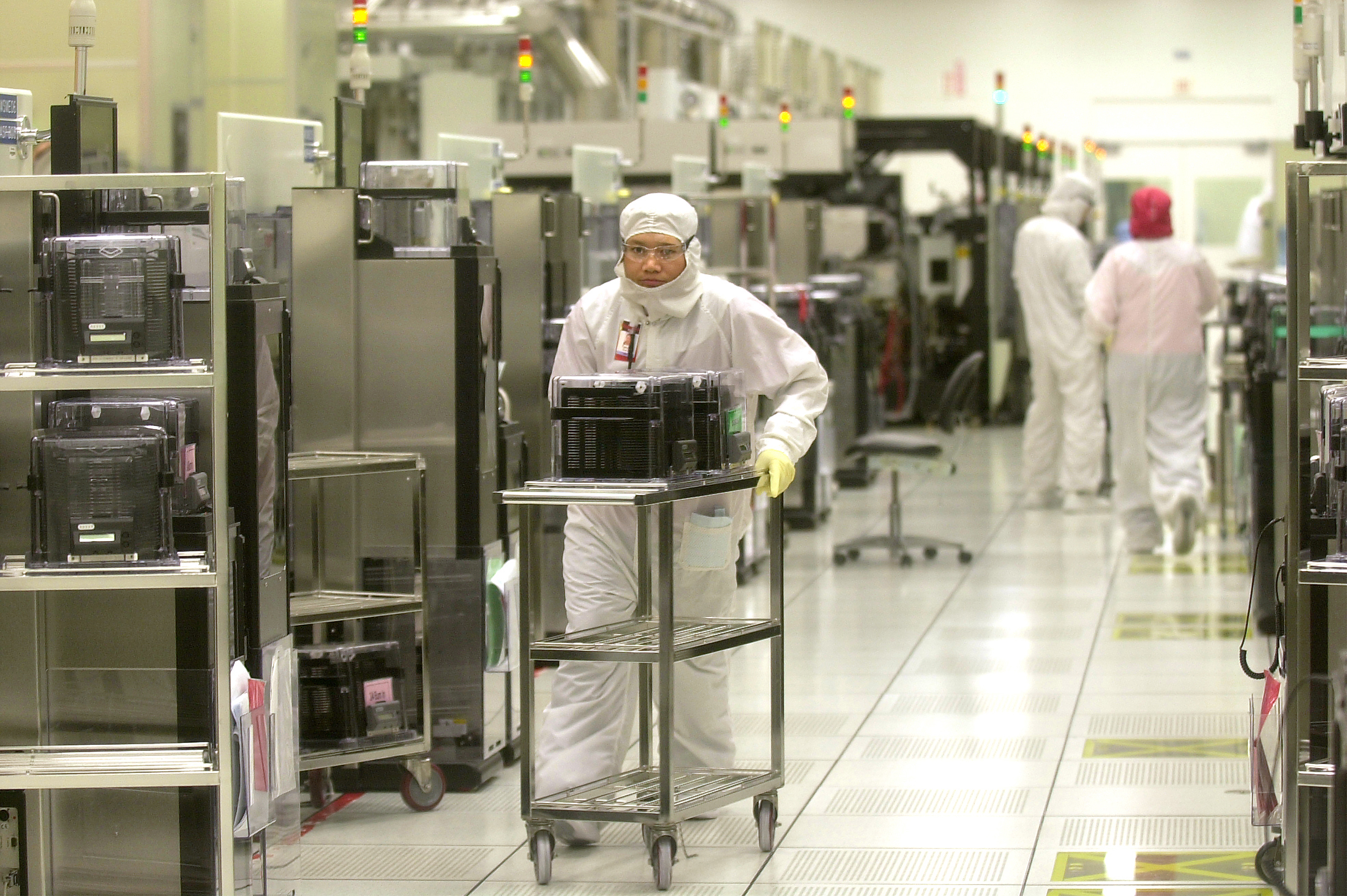

In the late 20th century, Southwest Washington welcomed a number of high-tech companies, including Hewlett-Packard, which established its Vancouver division in 1979; silicon wafer manufacturer Shin-Etsu Handotai, which established its Vancouver fab, SEH America, in 1979; ceramics manufacturer Kyocera, which opened its Vancouver branch in 1984; and Sharp Microelectronics Technology, which opened its circuit design center in Camas in 1995.

There was no single motivating factor that prompted technology companies to move into Southwest Washington. Tanner and his team cobbled together resources to be successful.

While states like Texas, North Carolina and Arizona were able to offer financial incentives, Tanner and his team were limited because Washington’s Constitution prohibits the transfer of public funds to private entities.

When they found themselves competing with other regions around the country, they would focus on things like housing costs and lifestyle.

Locally, Portland’s west side was the council’s biggest competition. Washington County, Ore., is home to Intel’s largest employment base and has attracted many other technology companies. “We were very keen to find those advantages that would differentiate us,” Tanner said.

The choice of whether to set up shop in Vancouver often came down to a financial analysis — income taxes, power rates, employment taxes, zoning, the availability of land, infrastructure and even seismic considerations. Sometimes employment training programs were offered.

It worked. These things all played into Kyocera’s decision to move here.

“Kyocera’s founder, the late Kazuo Inamori, chose Vancouver as a new manufacturing site in 1984, after expanding his San Diego plant to full capacity,” Bob Whisler, vice chairman of Kyocera International, told The Columbian. “As someone who loves the Pacific Northwest myself, I was thrilled with the decision. I had the honor of establishing Kyocera’s sales presence in Vancouver before the plant was built, and that assignment remains one of the highlights of my 41-year career.”

For SEH, Vancouver’s access to Japan and its electrical power costs were appealing when the company chose the spot for its American operations in the 1970s.

Enlarge

The Columbian files

Tax change boosts prospects

A change in tax law also boosted Southwest Washington. Initially, the state charged sales taxes on purchases of manufacturing equipment, which Tanner called a “showstopper” for certain industries, like semiconductor manufacturers, that have to invest millions in expensive tools.

In 1995, then-Gov. Mike Lowry signed into law a sales and use tax exemption and deferral for manufacturing machinery and equipment, pollution-control equipment, and high-technology research and development.

The governor was trying to recruit a steel plant to Kalama, according to the Washington State Department of Revenue. The state was competing against a location in Oregon. (Kalama won; the company, now called Steelscape, is a major employer.)

In 1996, WaferTech, a subsidiary of Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corp., and analog semiconductor manufacturer Linear Technology, which was later bought by Analog Devices, both opened in Camas. TSMC executives told The Columbian that it made sense for the company to have a presence in the metro area. The region’s steady supply of water and green power was a major advantage, they said.

What Tanner and his team started spurred growth in the region, with more and more companies moving here because of access to suppliers and other technology firms.

Enlarge

Amanda Cowan of The Columbian

Snowballing growth

Electronics manufacturer Silicon Forest Electronics’ founder started the company in Vancouver because of its proximity to the instrumentation and aerospace industries. Its customer base now spans North America. Today, the custom manufacturer’s largest clients are a cluster of companies like Insitu and Collins Aerospace that make drones and other “unmanned systems” in plants around the Portland region.

“That cluster is one of the largest unmanned-systems clusters in the world,” said Jay Schmidt, executive vice president and general manager at Silicon Forest.

It all goes back to the efforts made to recruit technology companies to the Pacific Northwest.

“Now people look at not just Hillsboro (Ore.) but this region as a developed high-tech area and high-tech landing spot,” said Tanner. “And that’s what we wanted to do.”

Enlarge

The Columbian files

Today’s technology

During the pandemic, disruptions rattled the global supply chain, preventing the international movement not only of people but of goods. A worldwide semiconductor shortage ensued.

This highlighted the importance of high-tech ecosystems like the one in Clark County.

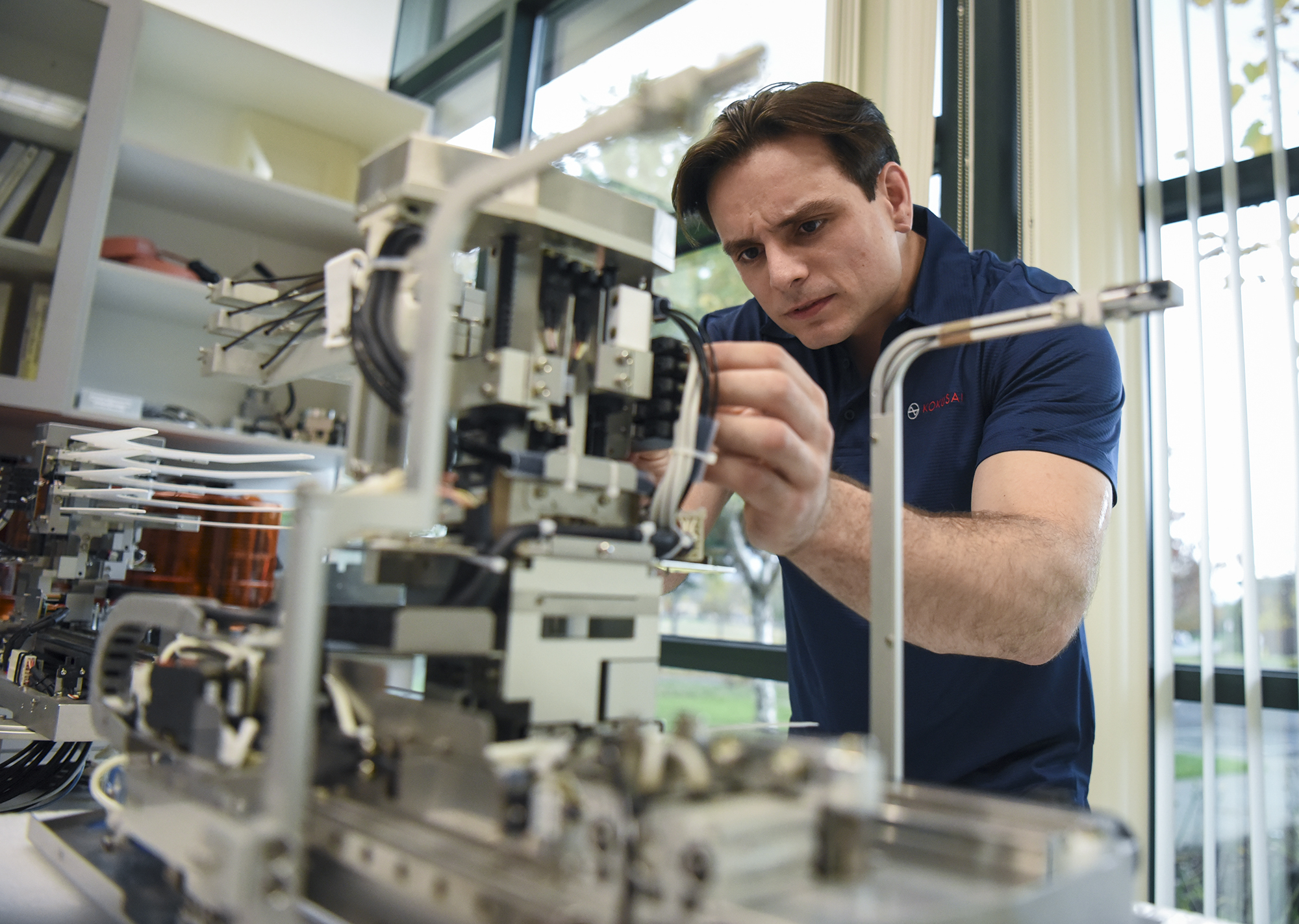

Kokusai is a Japanese company that manufactures diffusion and deposition vertical furnaces, which are used in the silicon wafer and semiconductor processes. It opened in Vancouver in 2005. A third of its U.S.-based staff are in Vancouver, working on sales, technical support, training and maintaining a parts warehouse.

Its Vancouver operation has allowed its U.S. customers to receive support and has enabled the company to acquire new orders.

It’s a “mutually beneficial and win-win relationship we have,” read a statement from Kokusai.

There are 10 local companies that are directly in this high-tech ecosystem, not including all those other companies supporting the industry.

Sigma Design creates and develops high-tech products. Kyocera manufactures cutting tools, cellphones, printers, copy machines and ceramic semiconductors. There’s the aforementioned Kokusai, SEH America, Analog Devices, WaferTech and Silicon Forest Electronics. ControlTek is another local electronics manufacturer. nLIGHT in Camas develops, designs and produces semiconductor and fiber lasers. UL Solutions tests, inspects and certifies products.

The industry employs thousands of people in the county, with an average annual wage of $90,012. Five of these companies are on the list of the Columbia River Economic Development Council’s top employers.

“Semiconductor and integrated circuit manufacturers and their associated supply chain partners are hallmarks of successful industry in Clark County and the greater Portland region,” said Jennifer Baker, current president of the Columbia River Economic Development Council.

Products from these companies, Baker added, are driving innovation nationwide in industries like consumer electronics, transportation, defense and health care. Camas’ Analog Devices, for instance, created components for NASA’s Mars rovers.

There are opportunities for more growth in Southwest Washington, which has become home to nearly the entire supply chain of electronics manufacturing from manufacturing equipment to silicon wafer and semiconductor production to product testing. But there’s more work to do.

Enlarge

The Columbian files

Recruiting talent

To flourish locally, high-tech companies need more labor.

“The availability of high-quality employees is very important, so that we can compete with higher labor productivity,” Neil Weaver, vice president of product development and applications at SEH America, told The Columbian. “Anything which helps to develop the workforce is important.”

“We’re hiring” was a statement expressed by many, if not all, of these high-tech companies.

To appeal to workers, companies say they need vocational training and affordable housing for employees entering the workforce.

“Your typical high school student might not be considering machine technology as a career, but we hope to change that,” said Angela Edginton-Burckhard, Kyocera’s deputy general manager of human resources.

“Many people assume that a high-tech manufacturing job always requires a four-year degree,” she said. “The fact is, our local community colleges offer associate degrees in machine technology that you can get in two years, and practical certificate programs you can get even sooner.”

Education is vital for employers across the industry.

“Programs and partnerships with local colleges and universities to promote semiconductor career paths are key to maintaining a pipeline of qualified engineers and maintenance technicians,” said John Michael, Analog Devices’ general manager for global operations and technology in Camas.

To compete with the rest of the U.S. market, companies like Kokusai need to develop semiconductor manufacturing equipment that adapts to the next generation of semiconductors desired by customers. Labor is key to this.

“Acquiring talented human resources to make our customers’ satisfaction higher is important,” read a statement from Kokusai.

That’s not the extent of the industry’s needs, however.

Last summer, Congress passed the U.S. Chips and Science Act, intended to bolster the semiconductor manufacturing industry. But for electronics manufacturers like Silicon Forest Electronics, it’s not just a shortage of semiconductors that is an issue.

Computer chips don’t work alone on a circuit board. There are other components — resistors, connectors and so on. Only 4 percent are made domestically. And they, too, are in short supply.

“We have a lead-time apocalypse,” said Schmidt. “What was 24 to 36 weeks can now be 18 months.”

Even if more semiconductors can be made domestically, if a resistor is made overseas and delayed, the completion of a circuit board will still be delayed.

Enlarge

Photo contributed by Analog Devices

Growing incentives

Government incentives could be an opportunity to attract more high-tech businesses here.

“Investments are needed to expand existing production and (research and development) capabilities to stay competitive,” said Analog Devices’ Michael. Because such projects are so expensive, expanding locally would be easier if companies received meaningful government incentives like those offered in other states and governments around the world, he added.

“If incentives are not provided, then companies are motivated to do the expansions elsewhere, to stay competitive against their peers,” said Michael.

“Right now, chipmakers on a global scale are deciding in which parts of the United States they will grow their industry presence to meet national and international customer demand,” said Baker of the CREDC. “Collaboration among state-level policymakers, education, and utilities partners regionally can help our community remain competitive in attracting high-tech manufacturing growth.”

With programs like the Chips and Science Act, companies are continuing to expand. In Camas, Analog Devices recently moved to a 24-hours-a-day, seven-days-a-week production system and installed new manufacturing tools, boosting its production capacity by nearly 50 percent.

SEH America announced last summer that it will expand its Vancouver facility to meet growing demand for silicon wafers.

Kyocera, which already employs about 300 people in Vancouver, is aiming to grow its local workforce.

What was once a smokestack economy now includes a diversity of industries, of which technology is a big one.

The region’s high-tech future is bright, said Stacey Smith, principal at ControlTek. Smith pointed to the investments being made here in technical education, preparing a new generation of high-tech workers.

“Combine the growing labor force with a business-friendly environment that attracts high-tech businesses to the region through reasonable business fees, low-cost energy and equitable tax policy, and (Southwest Washington) will become the go-to location for high-tech manufacturing companies,” she said.