The story of Cabanatuan has been told several times, including:

“Ghost Soldiers: The Forgotten Epic of World War II’s Most Dramatic Mission,” by Hampton Sides

“The Great Raid,” a 2005 film starring Benjamin Bratt and James Franco

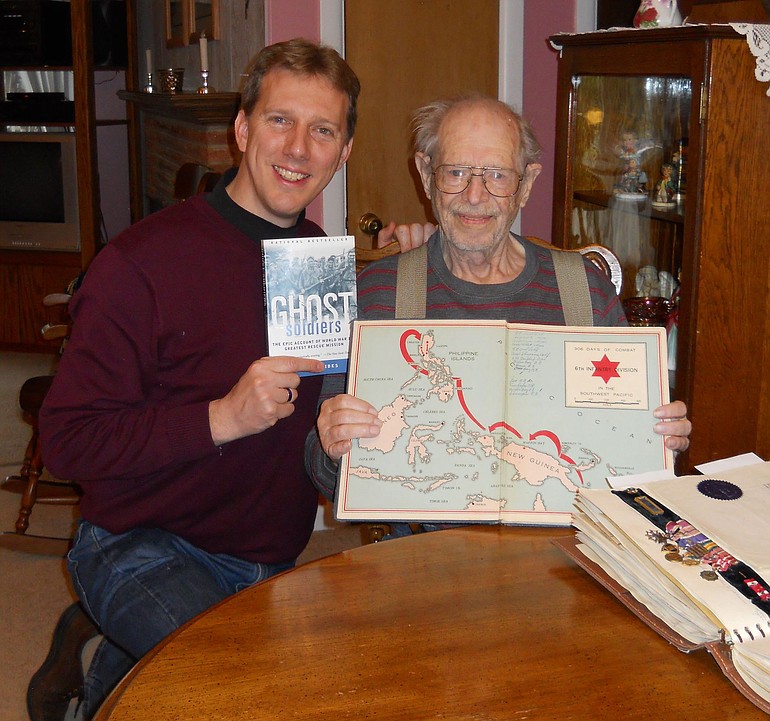

Dick Grafton lived a couple of minutes away from Jim Jacks.

Turns out there was another connection between the Vancouver families — one that stretches back 66 years to a place 9,000 miles away.

The place was Cabanatuan, a prisoner of war camp in the Philippines. Grafton was part of a secret operation that liberated the camp.

The POWs included one of Jacks’ relatives, who had survived three years of abuse, disease and starvation.

The story of Cabanatuan has been told several times, including:

"Ghost Soldiers: The Forgotten Epic of World War II's Most Dramatic Mission," by Hampton Sides

"The Great Raid," a 2005 film starring Benjamin Bratt and James Franco

Grafton died Feb. 14 at the age of 87. But a month before his death, Jacks had a chance to visit the World War II veteran and share stories about the chapter in history their families shared.

Jacks got to tell Grafton about his great-grandfather. Col. Alfred Oliver was an Army chaplain who’d been captured at Bataan in the opening stages of the war.

And Grafton got to expand on the story that reconnected the families. It was a story about dead birds. Grafton originally told it in a letter to the editor published in The Columbian on Jan. 7, in response to a quirky news story out of Arkansas.

Grafton wrote:

On Jan. 28, 1945, I was a young Army infantryman attached to a company of Army Rangers creeping through acres of 6-foot cogon grass, the sharp serrated grass of the central plains of Luzon Island in the Philippines, on a secret mission to rescue allied prisoners of war held in the Japanese camp Cabanatuan.

Creeping as stealthily as we could through this grass, we began to hear peculiar noises around us. “Plop!” over there, “Thump!” over here, all building up to a crescendo of “Plops, thumps and whaps!” We went to ground, unlimbering our small arms. One of our Filipino guerrilla scouts brought Captain Prince a dead bird, telling him the trail ahead was littered with dead and dying birds and his men were reluctant to go forward against such a powerful omen. But a few minutes with Prince and we all went forward to a successful mission.

… Every time I tell the story, I receive those “Oh, yeah, sure” looks from friends. Finally, I now have verification in The Columbian’s Jan. 4 story … about the red-winged blackbirds dying in flight over Beebe, Ark., on New Year’s night.

Jacks is a Washington state representative, and the Democrat from the 49th district said he always reads the letters to the editor. But Grafton’s letter reeled him in right from the start with the reference to Jan. 28, 1945.

‘Leaped off the page’

“That leaped off the page,” Jacks said. “Jan. 30 was when the rescue happened.

“At the end of the first paragraph, I almost fell out of my chair,” he said, noting the name of the POW camp. “So few people were involved: 120 U.S. soldiers and 80 Philippine guerrillas. And 66 years later, I’m living 14 blocks away from one of them.”

The Cabanatuan mission was launched after the Japanese decided to cover up their war crimes by killing POWs.

Grafton was part of a 6th Infantry unit that joined an Army Ranger battalion on the mission.

Jacks took notes during last month’s meeting and provided Grafton’s side of the conversation.

“Dick was in a heavy weapons company in the 6th Infantry Division. They had been fighting in New Guinea for about six months before attacking the Japanese in the Philippines,” Jacks said.

While Grafton was not a Ranger, he volunteered for the mission and was attached to the unit let by Col. Henry Mucci. The mission was to march 30 miles behind enemy lines, attack the camp, kill the guards and then bring 513 POWs back to U.S.-controlled territory.

Bored and curious

“The rule was, ‘Never volunteer,’” Grafton told Jacks. “Well, I went on the rescue mission because I broke that rule. I was bored, curious and this sounded interesting.”

It got way past interesting, according to Grafton’s account.

“The scariest part of the raid was crawling through a ravine and under a bridge with a Japanese tank on it,” Grafton told Jacks. “We were so close that I could hear two soldiers inside the tank talking. It felt like it took forever to crawl past that tank.”

“In addition to the camp guards, there were also 1,000 Japanese soldiers camped next to the road about a mile away northeast of the camp,” Grafton told Jacks. “We thought they would attack us at the POW camp or cut off our escape route. My job was to guard the escape route.”

Philippine guerrillas also held off Japanese pursuers at a bridge to aid the escape.

More than 500 Japanese soldiers were killed or wounded; two Rangers were killed.

Some of the weakened prisoners were hauled back along the 30-mile escape route in ox carts. They had endured a lot of punishment in Cabanatuan.

Jacks’ great-grandfather — who’d also served in World War I — was about 55 years old when he was captured in 1942.

“He was 6-foot-1 and weighed 215 pounds. When he was liberated, he weighed 115,” Jacks said. “He lost 100 pounds.”

Happy to be free

Sudden freedom had its own perils for the starving men.

“On the way back to U.S. lines, we stopped at the village of Talavera, and we had some time and the villagers had food for us all,” Grafton told Jacks.

“We were exhausted, having only had six hours of sleep over the last three days and the POWs were even more tired. The POWs gorged themselves on food. But they were so sick and they hadn’t eaten proper meals for three years that their stomachs just couldn’t handle it. I watched these poor starving men eat so much and then vomit and then eat and then vomit.”

“It was the most pathetic thing I’ve seen. But they were so happy to be free. We were all happy.”

Col. Oliver was part of a group that helped smuggle food and medicine into the camp, and he was tortured a couple of times, Jacks said. “He had a neck vertebra broken where was hit by a rifle butt. He wore a metal collar the rest of his life.”

According to a U.S. Army report, all officers in Cabanatuan were required to work — and the doctors and chaplains were singled out for particularly dirty jobs.

In a section on religious services, the Army report included an account by the Methodist chaplain.

He described severe restrictions on church services — particularly during the first three months, when chaplains weren’t even allowed to offer a grave-side prayer during the burial of a dead prisoner.

The Japanese discouraged escape attempts by assigning all prisoners to 10-man squads. If one escaped, the others in his squad would be shot.

Cabanatuan was established as a transfer site for slave labor, and an estimated 9,000 U.S. soldiers passed through the camp during the war.

In another twist, one of the prisoners shipped out of Cabanatuan to a slave labor camp in Japan was Jacks’ grandfather. “My grandfather was 6-foot-3,” Jacks said, “and he weighed 80 pounds when he was rescued.”

Bert Backstrom was a young Army artillery captain who met Oliver’s daughter just before the war. After they became engaged, the families of U.S. servicemen were evacuated.

“They had a four-year engagement,” Jacks said.

Jacks had hoped other members of his family would have a chance to meet Grafton.

Still, their two-hour conversation was pretty remarkable.

And Grafton reminded Jacks how incredible it was that the whole encounter hinged on “a flock of dead birds falling from the sky in Arkansas.”