Lifelong fascination with electronics benefited many

Melvin Jack Murdock was born in Portland on Aug. 15, 1917. According to diary excerpts in a biographical video called "A Life Well Lived," created by the Murdock Trust, he was all of 2 years old when he first grew fascinated with electronics -- by way of his Nebraska grandmother's phonograph. He grew skilled enough to become Franklin High School's resident electrician even while a student there.

"I would like to learn all there is to know about radio," he wrote while a teenager. "I shall probably make some inventions. I have at present several ideas for inventions which, if put into use, would be of great benefit for the people of the world."

Murdock graduated from Franklin and chose business rather than pursue a college education; with his parents' help, he bought a radio and appliance repair shop. That's where he was approached in 1936 by Howard Vollum, a radio technician and engineering graduate from Reed College, and the two of them worked together for years -- splitting up to do radar and radio operations work during World War II, and coming together again to found Tektronix in 1946.

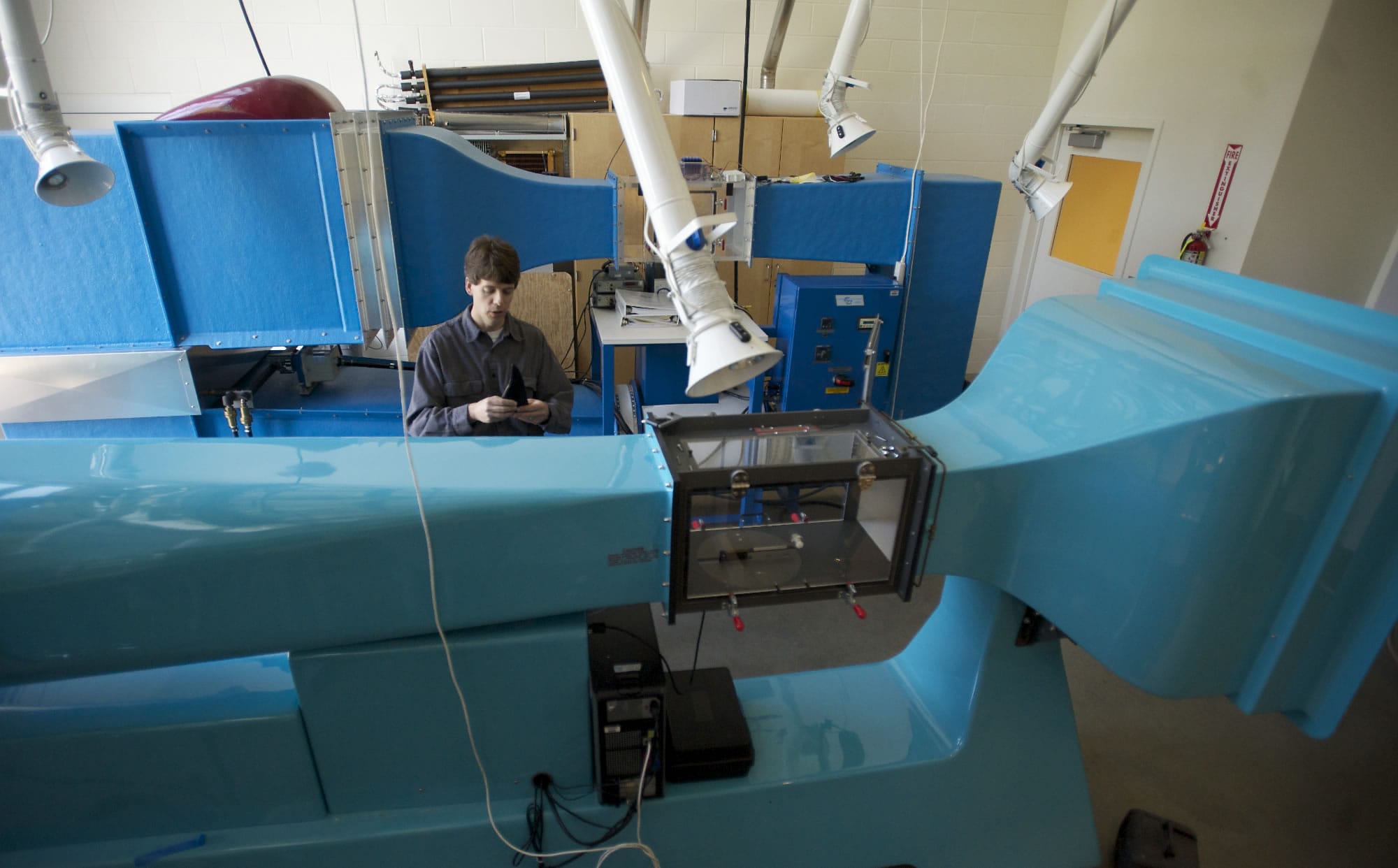

Tektronix caught fire with an oscilloscope that was smaller and handier than anything that had come before. After that came innovations in radio and television, health care, computers and aeronautics, to name just a few. It was the beginning of the so-called Silicon Forest, which broadened the economic base of the Pacific Northwest beyond lumber and water.

By the 1960s, "the word Tektronix was magic. It was the future," Murdock friend Ralph Crawshaw says in the video. The company had thousands of employees and thousands more enrolled in its educational programs; founder Murdock was just as interested in management innovation as he was in technical innovation. He joined on the board of the Menninger Foundation of Topeka, Kan., because he was enthusiastic about its new approaches to corporate psychology and human motivation.

According to the video, Tektronix was a precursor of the sort of loose, familial, creative business campus that's associated with cutting-edge outfits like Microsoft and Nike today.

"I think he felt (his business) was an opportunity to help society," Frank Consalvo, a friend and Tektronix employee, says in the video.

Murdock, on his way to becoming an Oregon legend, eventually bought an elegant home overlooking the Vancouver waterfront (at 5601 Buena Vista Drive). He had an office at Pearson Airfield and was an avid aviator -- which is what led to his death at age 53 in 1971. He was piloting a seaplane, attempting to take off from the Columbia River, when strong wind flipped the plane onto its back. A companion made it to shore, but Murdock's body was never found.

"It was very unfortunate because he still had lots of work to do," said Marian Haro, an employee of Melridge Aviation. "It was a loss to mankind."

When the will was read, it was found that Murdock, a lifelong bachelor, left token amounts to relatives but the vast bulk of his $80 million estate to a new charitable foundation.