MEDFORD, Ore. — Like any U.S. Navy chief storekeeper worth his salt, Albert S. Johnston kept precise records, taking care to print neatly.

His data-filled diary of the Zentsuji War Prisoners Camp on Shikoku Island in Japan where he spent all but a few days during World War II reflects that close attention to detail, says Jim Klug of Ashland.

“This is an historical treasure,” said Klug, commander of the Oregon Military Order of the Purple Heart and the historian for the group nationally.

Klug’s historian status put the diary in his hands for several months when he was loaned the diary by former Marine Jack Shimizu of Guam. Shimizu acquired the diary from a grandson who is married to one of Johnston’s descendants.

Klug hopes to make copies of the diary available for public review, likely online. He has returned the original to Shimizu.

“His timeline of events with all the details is just fascinating,” said Klug, an Army veteran wounded in Vietnam. “I can only imagine it didn’t meet with the approval of the Japanese that he was documenting all of this.”

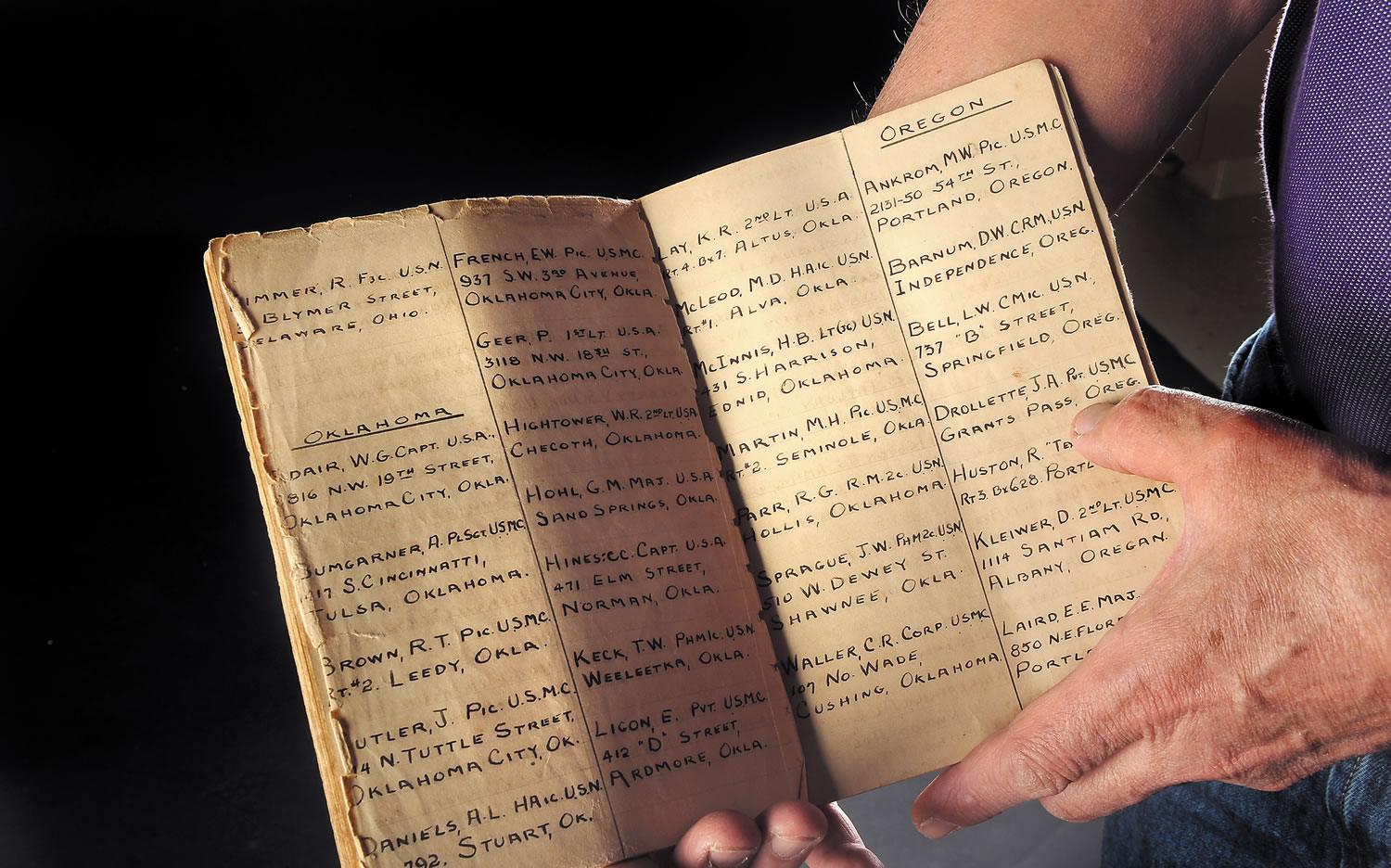

Johnston lists each American POW at the camp, placing them alphabetically in the state where they enlisted. Under Oregon, there are 14 POWs, including Marine Corps Pvt. J.A. Drollette of Grants Pass.

James A. Drolette was 81 and still living in Grants Pass when he was featured in a story in the Mail Tribune on Dec. 7, 2003. (In the diary, Johnston added one too many L’s to the private’s name.) Attempts to contact Drolette or his relatives for this story were unsuccessful.

The POW camp on Shikoku Island was established in January 1942 to hold the Americans captured on Guam. More POWs were later brought to the camp, including Australian, British, Canadian, Dutch and others, building up to nearly 1,000 prisoners.

Both Johnston and Drolette were captured Dec. 10, 1941, on the island of Agan. The POWs departed Guam on board the MS Argentina Maru on Jan. 10, 1942. They arrived at the camp on Jan. 16, and would spend the rest of the war there. The island is about 400 miles west of Tokyo.

Johnston, born in Waco, Texas, in 1902, originally had enlisted in the Navy in 1919, making it a career. He planned to retire as soon as he got back to the States, according to his diary.

Born in Grants Pass on July 19, 1922, where he graduated from high school in 1940, Drolette joined the Marines early in 1941. He was 19 when he was taken prisoner. He would retire from the Corps as a master sergeant after serving 28 years, including nearly four years as a POW.

Noting he was always worried about being taken prisoner in Vietnam, Klug said it would have been worse for those serving in WWII.

“In World War II, they didn’t have the Geneva convention rules,” he said. “All they had were basic principles of humanity.

“You can imagine the stories that were being circulated. The unknown of being captured was very frightening.”

Perhaps because he wanted to stay on an even keel, Johnston maintained several lists in his thin diary, which now is brown with age.

For instance, he kept a list of the wounded in Guam, including a double amputee and several GIs who had been bayonetted.

But much of what he recorded was mundane.

The long list of books kept by the POWs included “Mutiny on the Bounty” by Charles Nordhoff and James Norman Hall, and “The Grapes of Wrath” by John Steinbeck.

There also were a series of lectures given at the camp, apparently by speakers from within the POW ranks. Johnston’s list includes such topics as the evacuation of Dunkirk and the Java Sea battle.

“From what I’ve read about these POWs, in addition to mistreatment and lack of food, there was also boredom,” Klug said.

Johnston even maintained faithful records of his weight during his prison years. He weighed in at 154.8 pounds when captured, he reported. By Nov. 19, 1944, he weighed 120 pounds.

In his 2003 interview with the Tribune, Drolette recalled trying not to think of those big dinners his mom cooked back in Grants Pass.

“We were always hungry,” said Drolette. “Their idea of standard fare didn’t include breakfast and lunch and dinner.”

Instead, he survived on one daily meal of sticky rice and watered-down soup, he said.

Back home, his family members didn’t know he was alive until they received a letter on Sept. 8, 1942, nine months after he had been captured.

“Dear Mother, Dad and Sisters,” it began. “Although there are many things you want to know, the only things I can tell you is that I’m in good health and have no injuries.

“I know you are going to worry about me, Mother, but I wish you wouldn’t,” Drolette added. “Take care of everybody, Dad. Someday we’ll all be together again.”

Johnston’s diary included his hand-printed copy of a short broadcast he made to the U.S. on Nov. 1, 1943.

“Am hoping and praying for the war to end so I can come home,” he wrote. “Will retire as soon as I get back which I hope is very soon.”