A look at Detroit’s bankruptcy

DETROIT– A judge’s decision to allow Detroit to fix its finances in bankruptcy court raises a flurry of questions about what happens next. Here’s a look at what’s known about the next steps:

WHAT HAPPENS IN COURT?

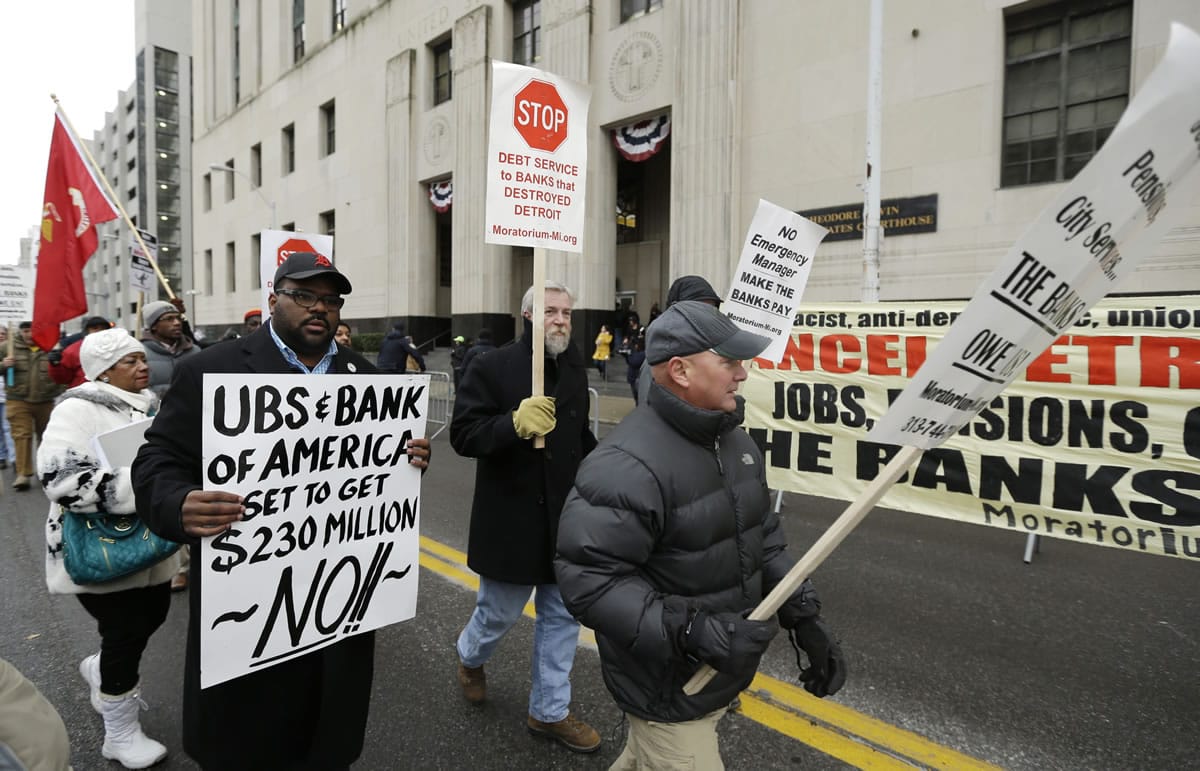

Bankruptcy opponents want to file appeals immediately to the 6th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Cincinnati, a move that could put the case on hold. They believe Judge Steven Rhodes is wrong in saying pensions can be cut, among other issues.

WHAT HAPPENS IN DETROIT?

The judge has told the city to come up with a plan to exit bankruptcy by March 1. But the city’s emergency manager, Kevyn Orr, says he’d like to have one ready weeks earlier. The plan could include anything from selling assets, such as art, to cutting pensions and more. Detroit would need the support of creditors and the judge to emerge from bankruptcy.

HOW LONG WILL IT TAKE?

Detroit is by far the largest city to go bankrupt and the timeframe isn’t known, especially because of appeals. Orr would like to get it done by next fall when his term ends as manager. Experts also warn the city’s legal bills and those of creditors will soar.

A look at Detroit's bankruptcy

DETROIT-- A judge's decision to allow Detroit to fix its finances in bankruptcy court raises a flurry of questions about what happens next. Here's a look at what's known about the next steps:

WHAT HAPPENS IN COURT?

Bankruptcy opponents want to file appeals immediately to the 6th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Cincinnati, a move that could put the case on hold. They believe Judge Steven Rhodes is wrong in saying pensions can be cut, among other issues.

WHAT HAPPENS IN DETROIT?

The judge has told the city to come up with a plan to exit bankruptcy by March 1. But the city's emergency manager, Kevyn Orr, says he'd like to have one ready weeks earlier. The plan could include anything from selling assets, such as art, to cutting pensions and more. Detroit would need the support of creditors and the judge to emerge from bankruptcy.

HOW LONG WILL IT TAKE?

Detroit is by far the largest city to go bankrupt and the timeframe isn't known, especially because of appeals. Orr would like to get it done by next fall when his term ends as manager. Experts also warn the city's legal bills and those of creditors will soar.

WILL THE LIGHTS GO OUT?

Orr says a ruling in favor of bankruptcy will allow the city to keep paying bills incurred since July 18. And it can keep police on the streets, firefighters on duty and streetlights aglow. City leaders have said those services have improved since the city filed for bankruptcy and police response times were near an hour.

WILL THE LIGHTS GO OUT?

Orr says a ruling in favor of bankruptcy will allow the city to keep paying bills incurred since July 18. And it can keep police on the streets, firefighters on duty and streetlights aglow. City leaders have said those services have improved since the city filed for bankruptcy and police response times were near an hour.

DETROIT — Detroit is eligible to shed billions in debt in the largest public bankruptcy in U.S. history, a judge said Tuesday in a long-awaited decision that now shifts the case toward how the city will accomplish that task.

Judge Steven Rhodes turned down objections from unions, pension funds and retirees, which, like other creditors, could lose under any plan to solve $18 billion in long-term liabilities.

But that plan isn’t on the judge’s desk yet. The issue for Rhodes, who presided over a nine-day trial, was whether Detroit met specific conditions under federal law to stay in bankruptcy court and turn its finances around after years of mismanagement, chronic population loss and collapse of the middle class.

The city has argued that it needs bankruptcy protection for the sake of beleaguered residents suffering from poor services such as slow to nonexistent police response, darkened streetlights and erratic garbage pickup — a concern mentioned by the judge during the trial.

“This once proud and prosperous city can’t pay its debts. It’s insolvent. It’s eligible for bankruptcy,” Rhodes said in announcing his decision. “At the same time, it also has an opportunity for a fresh start.”

Before the July filing, nearly 40 cents of every dollar collected by Detroit was used to pay debt, a figure that could rise to 65 cents without relief through bankruptcy, according to the city.

Emergency manager Kevyn Orr, who had testified the city’s current conditions are “unacceptable,” release a statement praising the judge’s ruling and pledging to “press ahead with the ongoing revitalization of Detroit.”

Rhodes said Tuesday that Detroit has a proud history.

“The city of Detroit was once a hard-working, diverse, vital city, the home of the automobile industry, proud of its nickname the Motor City,” he said. But he then recited a laundry list of Detroit’s warts: double-digit unemployment, “catastrophic” debt deals, thousands of vacant homes, dilapidated public safety vehicles and waves of population loss.

Detroit no longer has the resources to provide critical services, the judge said, adding: “The city needs help.”

Rhodes’ decision is a critical milestone. He said pensions, like any contract, can be cut, adding that a provision in the Michigan Constitution protecting public pensions isn’t a bulletproof shield in a bankruptcy.

The city says pension funds are short by $3.5 billion. Anxious retirees drawing less than $20,000 a year have appeared in court and put an anguished face on the case. Despite his finding, Rhodes cautioned everyone that he won’t automatically approve pension cuts that could be part of Detroit’s eventual plan to get out of bankruptcy.

There are other wrinkles. Art possibly worth billions at the Detroit Institute of Arts could be part of a solution for creditors, as well as the sale of a water department that serves much of southeastern Michigan. Orr offered just pennies on every dollar owed during meetings with creditors before bankruptcy.

Behind closed doors, mediators, led by another judge, have been meeting with Orr’s team and creditors for weeks to explore possible settlements.

Much of the trial, which ended Nov. 8, focused on whether Orr’s team had “good-faith” negotiations with creditors before the filing, a key step for a local government to be eligible for Chapter 9. Orr said four weeks were plenty, but unions and pension funds said there never were serious across-the-table talks.

Minutes after the ruling, a lawyer for the city’s largest union, said she would pursue an appeal at the 6th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Cincinnati. City officials got “absolutely everything” in Rhodes’ decision, she told reporters.

“It’s a huge loss for the city of Detroit,” said Sharon Levine, an attorney for the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, which represents half the city’s workers.

Opponents want to go directly to a federal appeals court in Cincinnati, bypassing the usual procedure of having a U.S. District Court judge hear the case.

Orr, a bankruptcy expert, was appointed in March under a Michigan law that allows a governor to send a manager to distressed cities, townships or school districts. A manager has extraordinary powers to reshape local finances without interference from elected officials. But by July, Orr and Gov. Rick Snyder decided bankruptcy was Detroit’s best option.

Detroit, a manufacturing hub that offered good-paying, blue-collar jobs, peaked at 1.8 million residents in 1950 but has lost more than a million since then. Tax revenue in a city that is larger in square miles than Manhattan, Boston and San Francisco combined can’t reliably cover pensions, retiree health insurance and buckets of debt sold to keep the budget afloat.

Donors have written checks for new police cars and ambulances. A new agency has been created to revive tens of thousands of streetlights that are dim or simply broken after years of vandalism and mismanagement.

While downtown and Midtown are experiencing a rebirth, even apartments with few vacancies, many traditional neighborhoods are scarred with blight and burned-out bungalows.

Besides financial challenges, Detroit has an unflattering reputation as a dangerous place. In early November, five people were killed in two unrelated shootings just a few days apart. Police Chief James Craig, who arrived last summer, said he was almost carjacked in an unmarked car.

The case occurs at a time of a historic political transition. Former hospital executive Mike Duggan takes over as mayor in January, the third mayor since Kwame Kilpatrick quit in a scandal in 2008 and the first white mayor in largely black Detroit since the 1970s.

Orr, the emergency manager, is in charge at least through next fall, although he’s expected to give Duggan more of a role at city hall than the current mayor, Dave Bing, who has little influence in daily operations.