ATLANTA — The first Ebola victim to be brought to the United States from Africa was safely escorted into a specialized isolation unit Saturday at one of the nation’s best hospitals, where doctors said they are confident the deadly virus won’t escape.

Fear that the outbreak killing more than 700 people in Africa could spread in the U.S. has generated considerable anxiety among some Americans. But infectious disease experts said the public faces zero risk as Emory University Hospital treats a critically ill missionary doctor and a charity worker who were infected in Liberia.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has received “nasty emails” and at least 100 calls from people saying, “How dare you bring Ebola into the country!?” CDC Director Tom Frieden said Saturday.

“I hope that our understandable fear of the unfamiliar does not trump our compassion when ill Americans return to the U.S. for care,” Frieden said.

Dr. Kent Brantly and Nancy Writebol, who will arrive in several days, will be treated in Emory’s isolation unit for infectious diseases, created 12 years ago to handle doctors who get sick at the CDC, just up the hill. It is one of about four in the country equipped with everything necessary to test and treat people exposed to very dangerous viruses.

In 2005, it handled patients with SARS, which unlike Ebola can spread when an infected person coughs or sneezes.

In fact, the nature of Ebola — which is spread by close contact with bodily fluids and blood — means that any modern hospital using standard, rigorous, infection-control measures should be able to handle it.

Still, Emory won’t be taking any chances.

“Nothing comes out of this unit until it is noninfectious,” said Dr. Bruce Ribner, who will be treating the patients. “The bottom line is: We have an inordinate amount of safety associated with the care of this patient. And we do not believe that any health care worker, any other patient or any visitor to our facility is in any way at risk of acquiring this infection.”

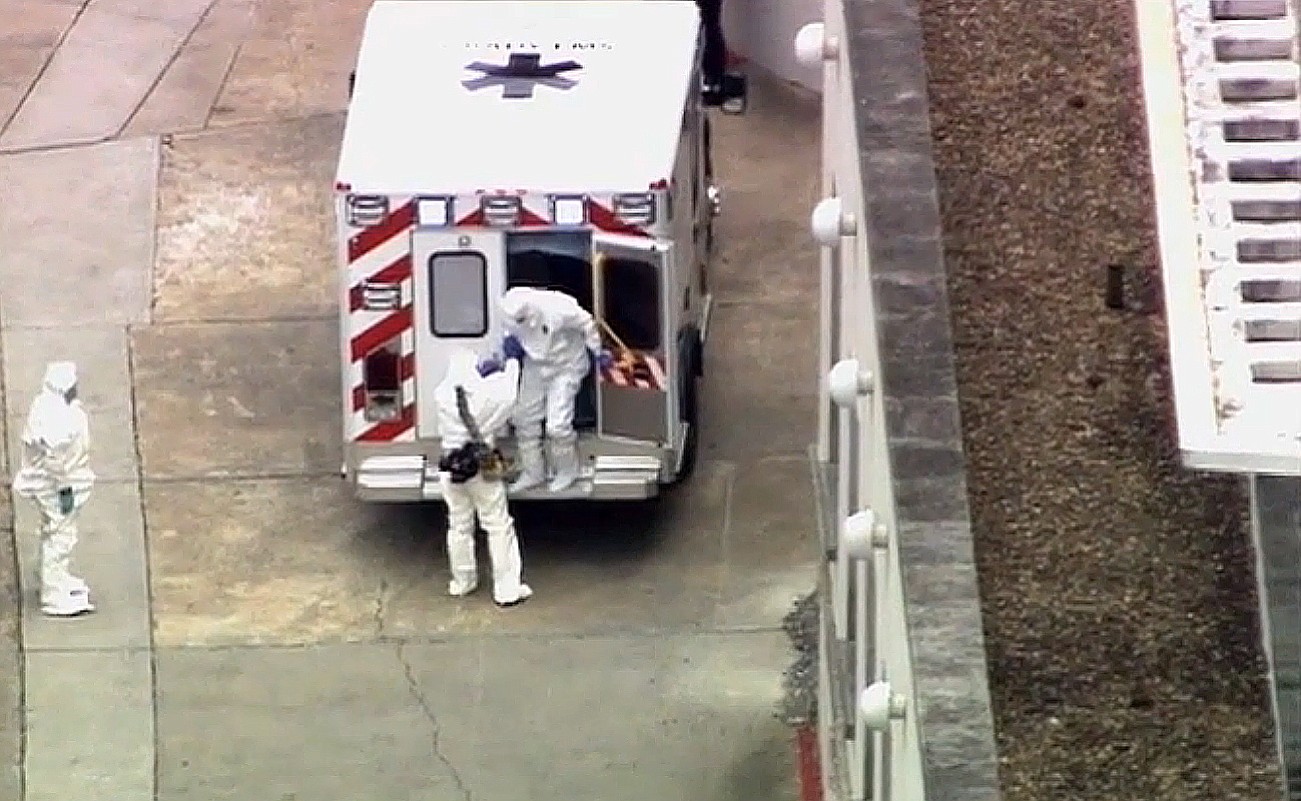

Brantly was flown from Africa to Dobbins Air Reserve base outside Atlanta in a small plane equipped to contain infectious diseases, and a small police escort followed his ambulance to the hospital. He climbed out dressed head to toe in white protective clothing, and another person in an identical hazardous materials suit held both of his gloved hands as they walked gingerly inside.

“It was a relief to welcome Kent home today. I spoke with him, and he is glad to be back in the U.S.,” said his wife, Amber Brantly, who left Africa with their two young children for a wedding in the U.S. days before the doctor fell ill.

“I am thankful to God for his safe transport and for giving him the strength to walk into the hospital,” her statement said.

Inside the unit, patients are sealed off from anyone who doesn’t wear protective gear.

“Negative air pressure” means air flows in, but can’t escape until filters scrub out any germs. All laboratory testing is conducted within the unit, and workers are highly trained in infection control. Glass walls enable staff outside to safely observe patients, and there’s a vestibule where workers suit up before entering. Any gear is safely disposed of or decontaminated.

Family members will be kept outside for now.

The unit “has a plate glass window and communication system, so they’ll be as close as 1-2 inches from each other,” Ribner said.

Dr. Jay Varkey, an infectious disease specialist who will be treating Brantly and Writebol, gave no word Saturday about their condition. Both were described as critically ill after treating Ebola patients at a missionary hospital in Liberia, one of four West African countries hit by the largest outbreak of the virus in history.

There is no proven cure for the virus. It kills an estimated 60 percent to 80 percent of the people it infects, but American doctors in Africa say the mortality rate would be much lower in a functioning health care system.

The virus causes hemorrhagic fever, headaches and weakness that can escalate to vomiting, diarrhea and kidney and liver problems. Some patients bleed internally and externally.

There are experimental treatments, but Brantly had only enough for one person, and insisted that his colleague receive it. His best hope in Africa was the transfusion of blood he received including antibodies from one of his patients, a 14-year-old boy who survived thanks to the doctor.

There was also only room on the plane for one patient at a time. Writebol will follow in several days.

Dr. Philip Brachman, an Emory public health specialist who led the CDC’s disease detectives program for many years, said Friday that since there is no cure, medical workers will try any modern therapy that can be done, such as better monitoring of fluids, electrolytes and vital signs.

“We depend on the body’s defenses to control the virus,” Dr. Ribner said. “We just have to keep the patient alive long enough in order for the body to control this infection.”

Just down the street from the hospital, people dined, shopped and carried on with their lives Saturday. Several interviewed by the AP said the patients are coming to the right place.

“We’ve got the best facilities in the world to deal with this stuff,” said Kevin Whalen, who lives in Decatur, Ga., and has no connection to Emory or the CDC. “With the resources we can throw at it, it’s the best chance this guy has for survival. And it’s probably also the best chance to develop treatments and cures and stuff that we can take back overseas so that it doesn’t come back here.”

EBOLA Q&A

By Misty Williams

Atlanta Journal-Constitution

Where did Ebola come from?

The virus first appeared in 1976 in two outbreaks, one in a village near the Ebola River in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Fruit bats are considered the likely host of the virus. Infection occurs among several animals, particularly primates. The current outbreak’s death rate is about 60 percent.

Why are Emory University Hospital and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention saying that bringing in Ebola patients does not pose a risk to the public?

Unlike flu, Ebola is not an airborne virus that you contract just by breathing. Infection occurs from contact with the blood, secretions or other bodily fluids of infected people or animals. In addition, the aircraft and ambulance used to transport the patients are specially designed to contain the virus, and the unit at Emory was built and equipped for Level 4 containment. Officials say those precautions are more than adequate.

Has this happened before in the United States?

No. But Ebola is just one type of hemorrhagic fever. Over the past decade, there have been five instances of people in the U.S. diagnosed with two types of hemorrhagic fever known as Marburg and Lassa. Those patients were treated without any spread of the disease.

What is hemorrhagic fever?

Viral hemorrhagic fevers can damage multiple parts of the body, including the vascular system and the body’s ability to regulate itself. Symptoms can include bleeding under the skin, in internal organs and from body orifices. Severely ill patients may also fall into a coma.

Why is this outbreak so bad?

It is occurring in countries that haven’t seen this disease before. CDC workers must essentially start from scratch in getting health systems in those countries up to speed.

Is there a cure for Ebola?

No. There’s not even a specific treatment. The patient either survives or he doesn’t. To help them survive, severely ill patients need rehydration with electrolyte solutions.

What are the symptoms?

Sudden onset of fever, intense weakness, muscle pain, headache and sore throat are typical. These are followed by vomiting, diarrhea, rash, impaired kidney and liver function, and in some cases bleeding. The incubation period is 2 to 21 days. A patient isn’t contagious before showing symptoms.