Valerie Miles is living with a tumor on the left side of her brain and the remnants of another tumor on the right side of her brain.

Surgery removed much of the first tumor. Chemotherapy and radiation stopped the tumor from growing for four years.

But a routine scan in April 2011 revealed a second, smaller tumor had grown on the other side of the Vancouver woman’s brain — this one too small to be surgically removed. Another bout of radiation and two years of chemotherapy once again stopped the growing.

But after completing chemotherapy in April 2013, Miles’ doctor told her she couldn’t stay on chemotherapy forever and her brain had already absorbed as much radiation as it could take. They were out of treatment options.

That reality prompted the 42-year-old mother of four teenagers to take part in a clinical trial for a new vaccine designed to use the body’s immune system to attack brain tumors.

“My doctor looked at me and said, ‘I don’t really have anything else to offer you,’?” Miles said. “So when he presented this, my first reaction was, ‘Yes.’?”

So Miles enrolled in the trial, becoming one of the first three people to receive the new vaccine.

“I feel very fortunate that I’m in a place where I’m eligible to participate,” she said. “Not many people are in that position.”

Vaccine trial

The vaccine, known as ADU-623, uses a genetically modified version of the bacterium listeria monocytogenes — the bacterium that in its native form causes the listeria infection — and a specific mutated protein found only in cancer cells, said Keith Bahjat, a researcher at Providence Cancer Center in Portland. The protein used is found in more than half of brain cancers, he said.

The idea is to provoke an immune response to the bacterium, assuming the immune system will then also target the proteins found in the cancer cells, Bahjat said. The goal, he said, is to wipe out the pieces of tumor that are so intertwined with brain tissue they cannot be completely removed by surgery.

“It’s those residual bits in the brain that always end up growing back and killing the patient,” Bahjat said. “The vaccine is not just prolonging the lifespan of the patient, it’s to prevent the tumor from ever recurring.”

Bahjat worked with scientists at Aduro BioTech, who have engineered a version of the listeria bacterium for use as a vaccine for other cancers, to create ADU-623. While the technique isn’t new, they are using a more novel approach, Bahjat said.

Many prior vaccine development efforts have focused on vaccines with similar safety profiles as traditional vaccines, such as the flu vaccine.

“We believe you have to hit the immune system harder than that,” Bahjat said. “Our vaccine is a much more potent vaccine in the sense that it really revs up the immune system.”

This specific vaccine is in clinical trial at only Providence Cancer Center in Portland. Currently, the trial is in its first phase, which is focused on safety.

Researchers are treating groups of three patients with the vaccine. The first group, which included Miles, just completed its course of treatment.

Each patient received four doses of a set amount of the vaccine in three-week intervals. After the final dose, the patients will get an MRI of the brain to determine whether the tumor progressed during treatment. Then, the patient is essentially done with the trial, Bahjat said.

After researchers determine the dosage amount that is safe for patients, they’ll increase the amount and enroll another three patients and repeat the process. They’ll complete that cycle until they can determine the maximum safe dose, Bahjat said.

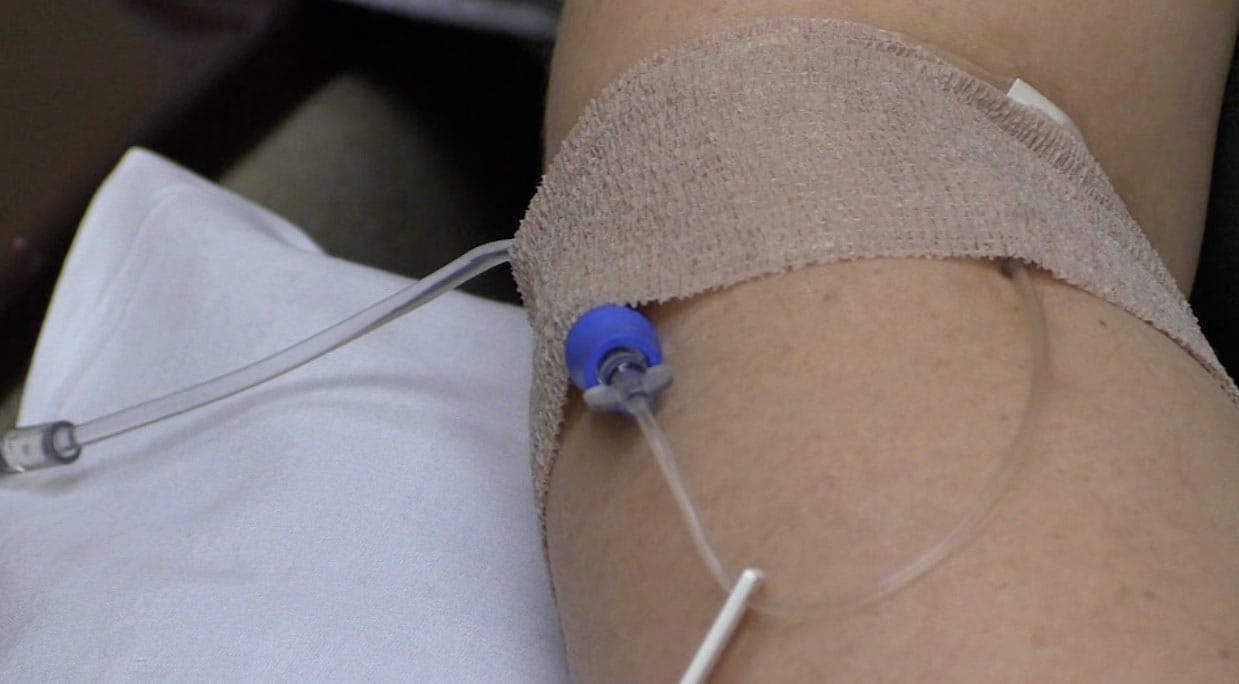

Miles received her last infusion April 30. After each infusion, Miles said she experienced fevers and some nausea, but she said they resolved within a few hours.

Those side effects tell researchers the vaccine is doing exactly what it’s designed to do: Elicit an immune response, Bahjat said.

Bahjat expects the first phase of the trial will be complete by the end of this year. Then they can move to Phase 2, which looks for efficacy of the vaccine.

Providence Portland Medical Foundation provided enough funding to manufacture thousands of doses of the vaccine, but the launch of the second phase is likely to be dependent on getting additional funding to support the necessary clinical care, Bahjat said.

The third phase of the trial will expand the participant population and include larger control groups in order to gain enough information to submit an application for drug approval to the Food and Drug Administration, he said.

Even though the vaccine is in its early stages, Miles is hopeful it can help stop her tumors from growing. And if the trial is successful, Miles said it will give other people diagnosed with brain tumors hope that they can beat the cancer.

Currently, people diagnosed with high-grade glioma, the most common primary brain tumor in adults, have a median life expectancy of just 14 months. It’s been more than eight years since Miles was diagnosed in fall 2005.

“One of my doctors, she keeps saying how I beat the odds,” Miles said. “You just want everybody to be able to beat the odds.”