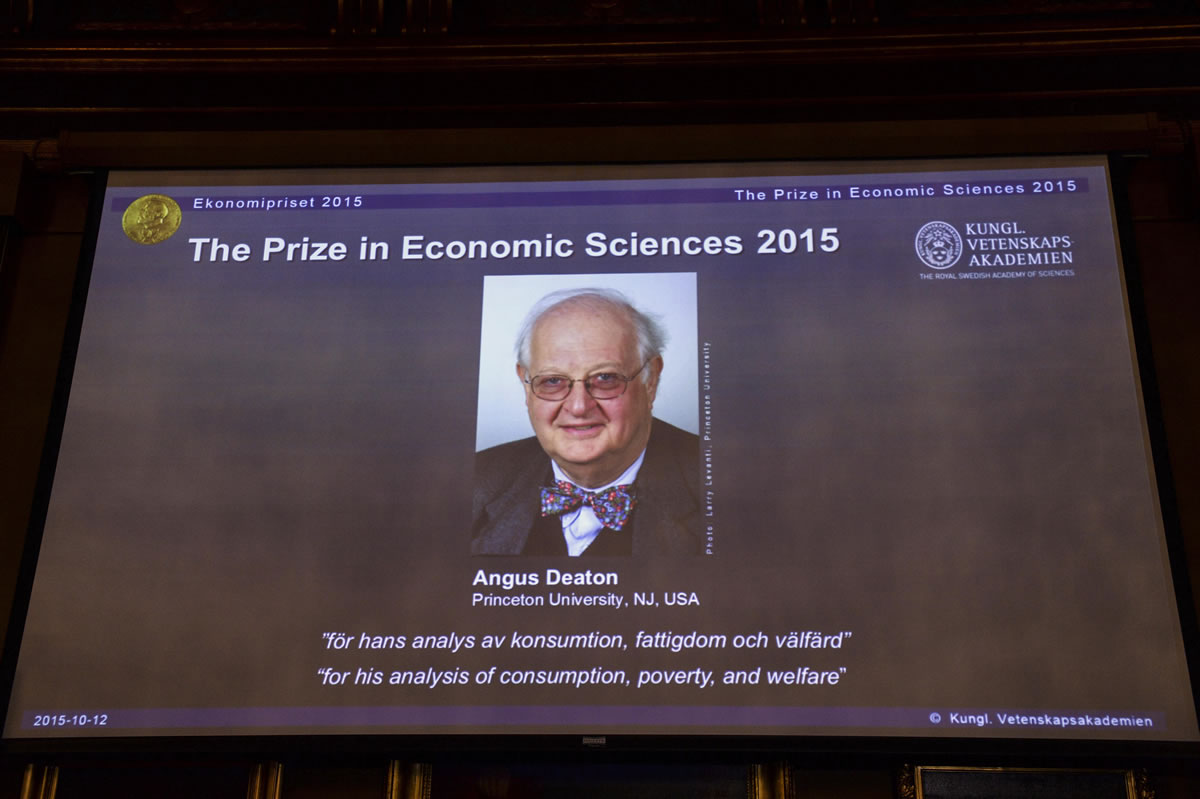

STOCKHOLM — Angus Deaton of Princeton University won the Nobel prize in economics Monday for improving understanding of poverty and how people in poor countries respond to changes in economic policy.

Deaton, 69, won the 8 million Swedish kronor (about $975,000) prize from the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences for work that the award committee said has had “immense importance for human welfare, not least in poor countries.”

The secretary of the award committee, Torsten Persson, said Deaton’s research has “shown other researchers and international organizations like the World Bank how to go about understanding poverty at the very basic level.”

Persson praised Deaton’s work for illustrating how individual behavior affects a broader economy and demonstrating that “we cannot understand the whole without understanding what is happening in the miniature economy of our daily choices.”