While antiviral drugs could cure about 90 percent of the estimated 150 million people in the world with hepatitis C, access to those drugs — and even a hepatitis C diagnosis — is low, according to the World Health Organization.

In the U.S., where an estimated 2.7 million to 3.9 million people have chronic hepatitis C infection, patients now have access to new drugs to treat the bloodborne virus — medications with far fewer side effects and better cure rates than previous treatments.

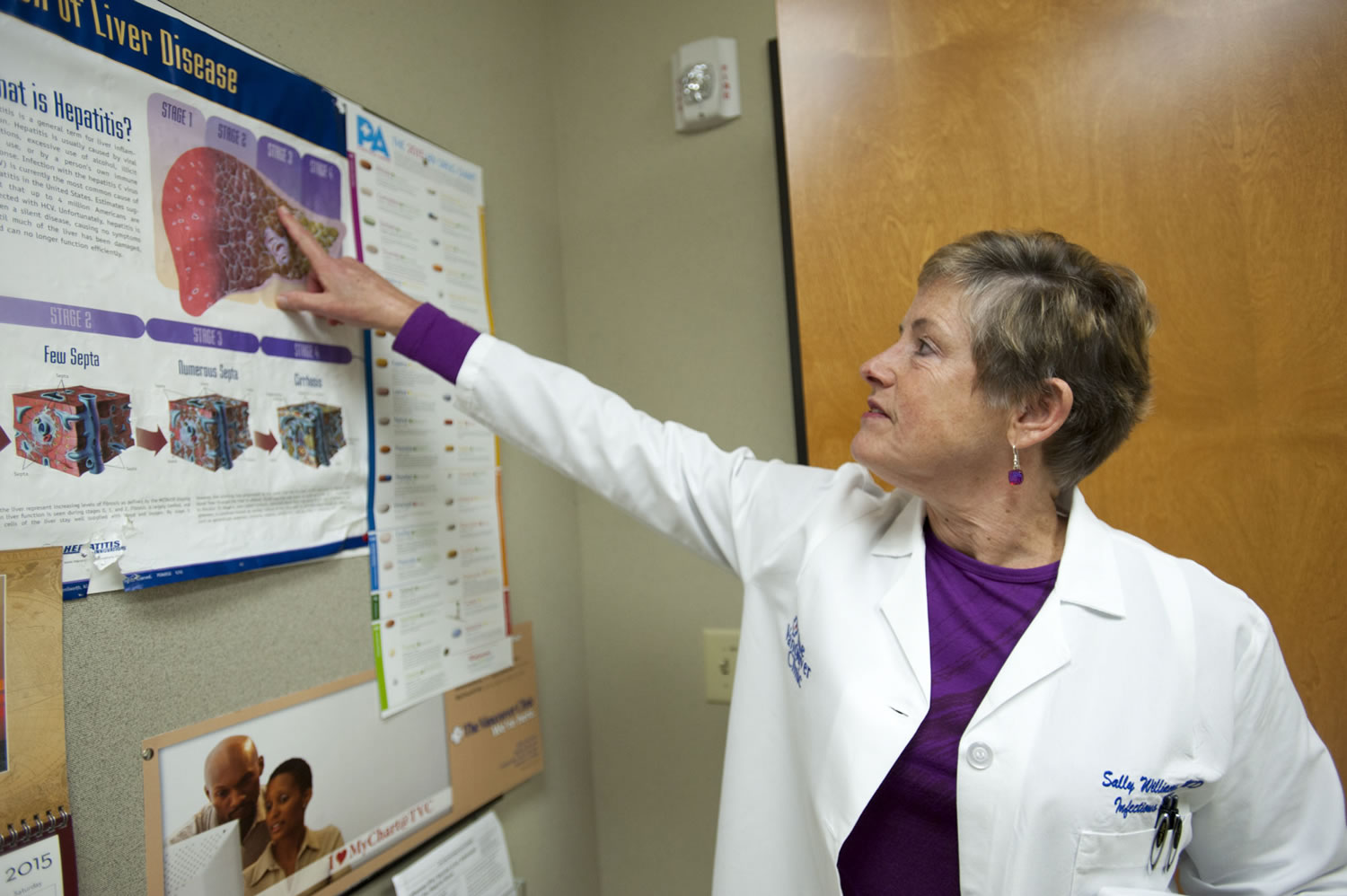

“The whole field of hepatitis C just revolutionized in these last two years,” said Dr. Sally Williams, an infectious disease doctor at The Vancouver Clinic.

Hepatitis C is a liver infection caused by a virus, and, Williams said, it is “unbelievably common.”

What is hepatitis C?

Hepatitis C is a liver infection caused by a virus. Chronic hepatitis C, a long-term infection, is a serious disease that can lead to chronic liver disease, cirrhosis (tissue scarring) and death, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The only way to contract hepatitis C is through blood transmission. Most people who have contracted the infection got it through IV drug use, received a blood transfusion in the 1980s or got a tattoo from someone who reused needles, said Dr. Sally Williams, an infections disease doctor at The Vancouver Clinic. “This is really a treatable disease,” Williams said.

Since Williams began caring for hepatitis C patients in the community in early 1998, she has seen about 7,000 patients. This year, Clark County Public Health recorded 721 cases of chronic hepatitis C.

Some people clear the infection from their bodies without medication and don’t develop a chronic infection. But for the majority of people — 70 to 85 percent — hepatitis C becomes a long-term, chronic infection, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Chronic hepatitis C is a serious disease that can lead to chronic liver disease, cirrhosis (tissue scarring) and death, according to the CDC. About 25 percent of people with hepatitis C will develop cirrhosis, the last stage of tissue scarring before liver cancer.

Thirty years or more could pass until the disease progresses to cirrhosis, which is when patients typically begin to experience symptoms, Williams said. That’s why many people don’t even know they have the disease until it shows up on routine blood tests, which only widely began including liver tests in 2000, Williams said.

“There seems to be a large undiagnosed population out there,” she said.

“Every week, I see eight people with hepatitis C who didn’t know they had it,” she added.

The only way to contract hepatitis C is through blood transmission. Most people who have contracted hepatitis C got it through IV drug use, received a blood transfusion in the 1980s or got a tattoo from someone who reused needles, Williams said.

“It’s not easy to get,” she said. “There’s also a huge misconception that it’s really fatal.”

And the new drugs on the market have caused the cure rate for hepatitis C to shoot up.

From 1990 to December 2013, the drug used to treat hepatitis C required multiple pills and weekly injections. The drug made patients extremely ill and required treatment for one year, Williams said.

“It’s a really difficult treatment,” she said.

But, Williams said, it worked. About 50 percent of her patients were cured using the drug.

For years, people waited for less-harsh treatments. Those drugs arrived in late 2013 and finally reached the market a year later.

Now, there are four different pills used to treat hepatitis C, one for each of the four different strains of the virus. The drug used for the most common strain, which accounts for about 75 percent of U.S. infections, is Harvoni.

“Harvoni is truly a miracle pill,” Williams said.

Patients take a single pill each day for eight to 12 weeks and have no side effects. Best of all, the drug has a 90 to 95 percent cure rate, Williams said.

“We went from this extremely toxic treatment that cures 50 percent to this super easy pill,” she said.

The downside is Harvoni retails for $1,200 per pill. Most insurance companies will cover the treatment if that patient has reached Stage 3 fibrosis, one stage shy of cirrhosis. Most doctors, however, would prefer to treat the patient when they reach the second stage, Williams said. The reason is obvious: less damage to the liver.

“We had hoped that as more drugs came out, the price would go down,” Williams said. “But that never happened.”

“There doesn’t seem to be a time in sight when the prices will go down,” she added.

Since Harvoni became available in November 2014, Williams has had more than 200 patients take the medications, the majority of whom have completed their treatment; the rest are still taking the drug. The cure rate for her patients is about 93 percent, Williams said.

In the 17 years prior, Williams treated about 400 hepatitis C patients with medication. Most people feared the harsh medication and prolonged beginning the treatment until cirrhosis was imminent, she said.

Now, however, people who pushed off treatment are lining up for the new drugs, Williams said. Though some are left to wait until their liver damage progresses far enough to qualify for insurance coverage of the treatment, once a person is cured, the liver damage stops, she said.

“This is a cure,” Williams said. “This is really a treatable disease.”