If You Go

• What: Fort Vancouver Archaeology Field School.

■ When: June 23 through July 25; open to public, 9 a.m. to 4 p.m., Tuesdays through Saturdays. (Closed July 3, July 4.).

■ Where: South of east Fifth Street, between fort stockade and Pearson Air Museum.

In 1852, a Hawaiian native operated a one-man cooper’s shop at Fort Vancouver, assembling wooden barrels for the Hudson’s Bay Company’s global trading empire.

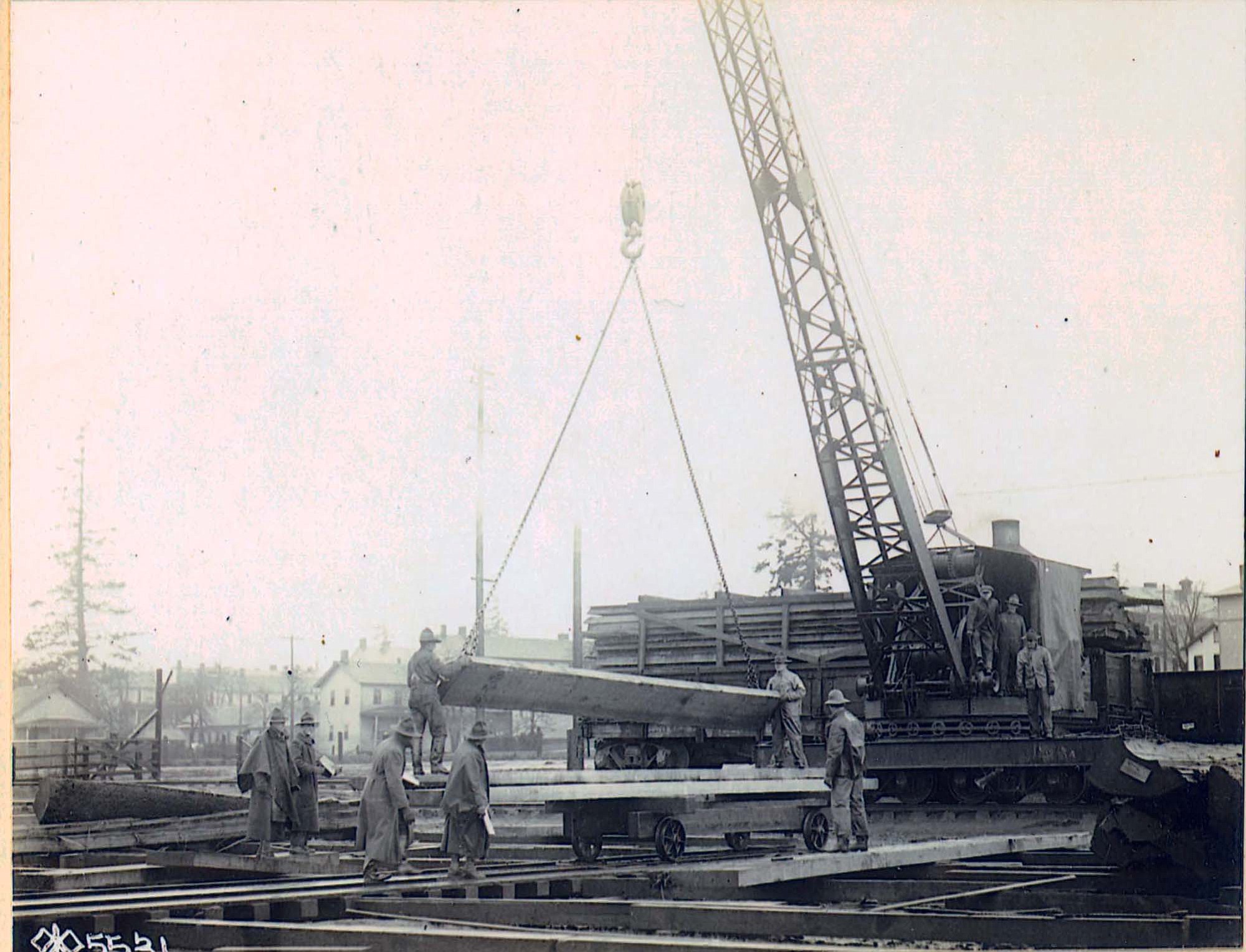

The scale of production on the site increased considerably 65 years later, when the U.S. Army built the world’s biggest spruce mill for World War I military planes.

Both eras will share the focus of this summer’s archaeology field school at Fort Vancouver National Historic Site.

If You Go

• What: Fort Vancouver Archaeology Field School.

? When: June 23 through July 25; open to public, 9 a.m. to 4 p.m., Tuesdays through Saturdays. (Closed July 3, July 4.).

? Where: South of east Fifth Street, between fort stockade and Pearson Air Museum.

The National Park Service partners with Portland State University and Washington State University Vancouver in the annual session, which gives college students some hands-on experience in archaeology. It also gives members of the public a chance to observe the careful excavations, the precise record-keeping and the preservation of artifacts involved in an actual archaeological project.

This year’s field school, which begins on June 23, will be in a very accessible, user-friendly spot for the public. It is an open area just south of East Fifth Street, between the fort stockade and Pearson Air Museum.

From 1825 to 1860, Fort Vancouver was the regional headquarters and supply depot for the Hudson’s Bay Company. Coopers made barrels for shipping goods.

“We use boxes for everything,” said Doug Wilson, National Park Service archaeologist and principle investigator at the dig. “The Hudson’s Bay Company used wooden barrels.

“Animal pelts were shipped in barrels. Salted salmon was packed in barrels, and they had to have a barrel maker on site,” Wilson said.

The last known cooper to work in the shop was a Hawaiian named Spun Yarn.

“Spun Yarn is on the rolls of employees of the Hudson’s Bay Company,” Wilson said. Spun Yarn was the only cooper listed at Fort Vancouver in 1852; he evidently died in 1853.

When the field school begins on Tuesday, June 23, students will begin preliminary testing at two sites suspected to be the housing for the Fort Vancouver coopers.

“We will put in test units 2 meters square — excavating down and trying to find remnants of houses: a hearth or a section of house floor, or possibly an architectural feature,” he said.

Students working on the spruce mill portion of the project will look for concrete foundations that would establish the footprints of the main mill, repair shops and machine shops.

“If they are in good enough condition, we will expose them for the public to see,” Wilson said. That would add a timely feature in a couple of years, when the nation observes the centennial of the U.S. entering World War I.

Archaeologists also will be working in areas where 5,000 soldiers, who were the mill-hands, lived in bunkhouses and a tent city.

The move to the Spruce Mill Trail portion of Fort Vancouver means digging is done at the site known as the workers village, where field schools were held over the past few summers.

“We are currently analyzing eight years of information and finds,” Wilson said.

If any new research questions develop from that site, they will come out of that analysis process. While a future generation of archaeologists might want to resume digging, the excavation phase of archaeology at the village “is closed for now,” Wilson said.