It was an intense moment on high school baseball’s biggest stage.

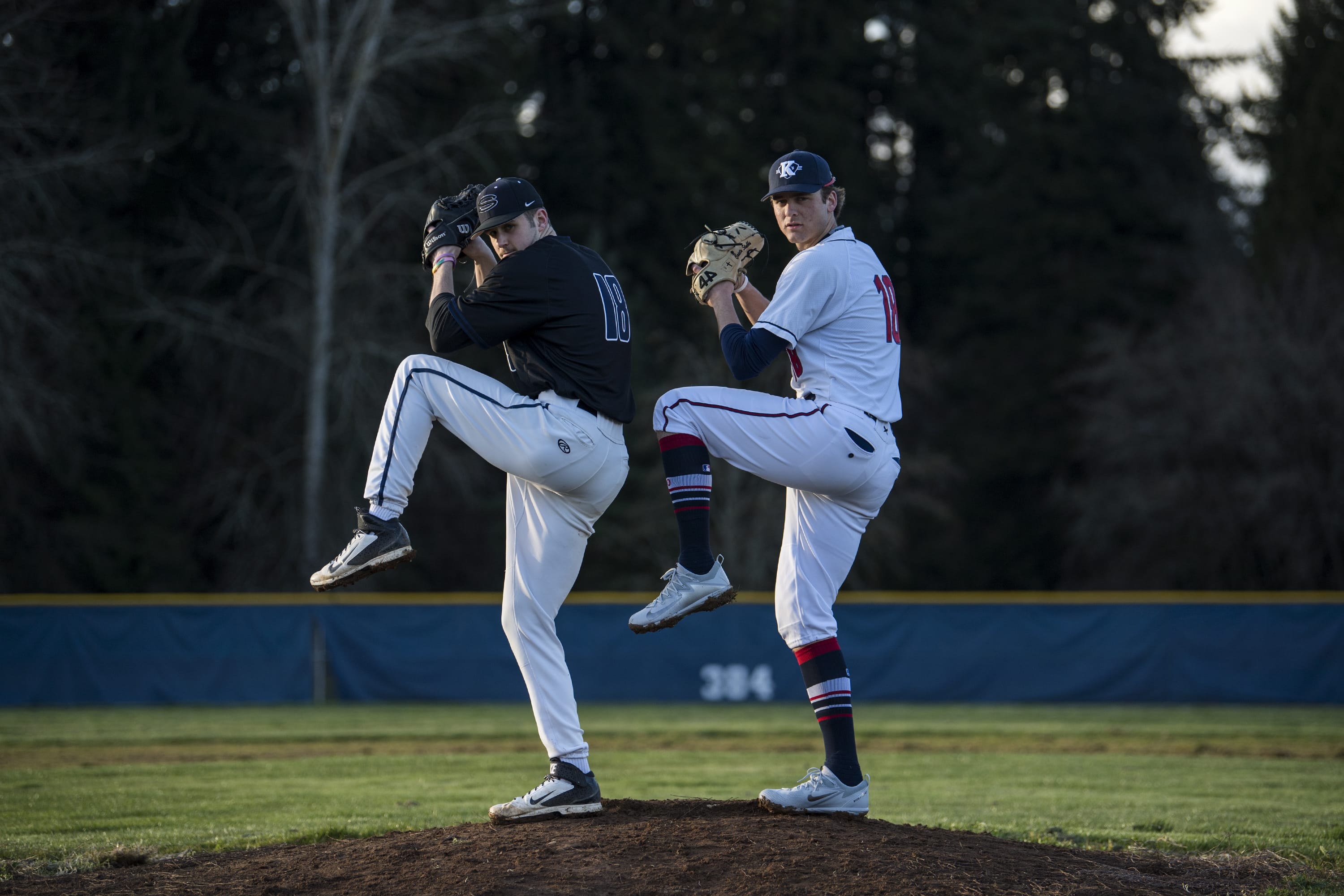

King’s Way led Cedar Park Christian by one run in the bottom of the seventh inning in the 1A state championship game. The lead was largely due to a stellar outing from Knights ace Damon Casetta-Stubbs, who retired 10 of the last 12 batters he faced.

With no outs and a 3-1 count, he suddenly left the game.

In that instance, his departure from the mound was not by choice.

Last season, the Washington Interscholastic Activities Association followed a national mandate and implemented a pitch count rule. It limits pitchers to 105 pitches per game and requires rest between outings. But unless you were at a game where a pitcher left suddenly in the middle of an at-bat, such as the 1A state championship, the change may not have been apparent.

Now with the 2018 season in swing, what affect has the rule had on prep baseball in a year’s time?

There hasn’t been a drastic change in gameplay. But the implementation underscores an effort by the National Federation of State High School Associations to make the game safer for pitchers and ensure high school athletes are able to continue their careers with a lower risk of injury.

“We’ve faced teams who have thrown kids 150, 160 pitches in games and it’s just not healthy obviously,” Casetta-Stubbs, a Seattle University commit, said. “Them implementing that is pretty good.”

Casetta-Stubbs plans for a future on the mound after high school. Even without a required rule, he’s always self-enforced a pitch count.

“Ever since I’ve started pitching I’ve done pitch counts,” Casetta-Stubbs said. “My parents, pitching coaches, it’s been important to us. … I never throw over 100, if I do it’s 101 and it’s the last batter.”

Once a pitcher hits 105, he is considered an ineligible player, per the rule. Any additional pitches would result in that team forfeiting the game. The WIAA was not made aware of any such forfeits during the rule’s first season after being instituted, WIAA assistant executive director Cindy Adsit said in an email.

“It is possible, however, that a team had to forfeit due to exceeding the maximum number, and did not appeal,” Adsit said.

Perhaps there was extra attention to the rule due to its newness. To players and coaches, it took some adjustment.

Late in the season, it wasn’t entirely uncommon for the pitch limit to be reached in the middle of an at-bat.

Skyview senior Daniel Copeland was forced to exit a loser-out game in the postseason last year with two outs in the seventh inning.

Union led Camas 7-6 with two outs and a full count in the top of the sixth when starter Jimmy Borzone hit the pitch limit. The reliever, Johnny Lee, entered and threw one pitch to close out the inning.

The teams had reliable arms in line to replace their starters. But Copeland was admittedly miffed.

“In the moment it’s really frustrating to have to come out of a game when you did nothing wrong, you just reach a number,” the Gonzaga commit said.

But Copeland, who said the rule doesn’t typically affect him because of his style of pitching, supports it despite its occasional inconvenience.

“I think it’s great to protect people,” Copeland said. “An arm only has so many throws, you can’t get around that.”

Before the pitch count rule was mandated, coaches managed their pitchers on an ad-hoc basis.

And because of that, problems arose.

Union head coach Ben McGrew used USA Baseball’s Pitch Smart protocol, which maps out daily maximum pitches and corresponding rest day requirements based on age. McGrew and his coaching staff would input each pitcher’s number of throws into an app for guidance on how to manage their rotation.

“You’d always like to think that you were pretty good at managing the arms knowing what you know now, but I definitely used it three years ago,” McGrew said.

When McGrew was a player, first for Hudson’s Bay, then Tacoma Community College and Oregon State in the early 2000s, pitching was viewed much differently, he said.

Studies warning of kids going for long outings were not as readily available.

“If you had a stud pitcher, you’d throw him Monday and Friday then again on Wednesday,” McGrew said, “and however many pitches it took to throw a complete game. If it was 130 he threw 130. That’s what your best pitchers did.”

Putting that many miles into a developing arm had its costs. Injuries arose–maybe not always in the moment, but later down the line.

In 2010, the American Journal of Sports Medicine conducted a 10-year study that followed 481 youth pitchers and determined that kids pitching more than 100 innings in a year “significantly increases the risk of injury.” As a result,”limiting the number of innings pitched per year may reduce the risk of injury.”

One year, McGrew and his staff were scouting a potential playoff opponent. A player who McGrew said is pitching in college now had thrown 120 pitches three days prior. He closed the game they scouted, throwing about 50 pitches. Then, he started a game later that day and threw 105 pitches.

The following week, McGrew said, that player suffered an elbow injury that required Tommy John surgery, a ligament repair procedure that can require a year or more of rehabilitation.

“You won’t see that anymore with the pitch count stuff,” McGrew said. “You always hear about the guys who [are able to throw an exceedingly high number of pitches] and that’s not necessarily a good thing. It ends up catching up to them.”

When initially proposed, the WIAA required three calendar days rest for an outing of 91-125 pitches, which would have given Washington one of the highest pitch counts in the country.

“We were all kind of looking around in shock,” Skyview coach Seth Johnson said.

At that time, King’s Way coach Gregg Swenson was the pitching coach at University of Portland.

He took notice. He then took to Twitter.

Swenson tweeted at the WIAA multiple times challenging its initial proposal of a 125 pitch count, which was decided by an advisory committee of baseball coaches across the state.

When the WIAA tweeted out an opportunity to submit a question to executive director Mike Colbrese, Swenson leapt at the opportunity.

“Do you plan to allow the BAC proposed Pitch Count plan to go through?” Swenson tweeted, alluding to the Baseball Advisory Committee. “It allows the most pitches in the country & fewest rest days.”

Colbrese, according to multiple coaches watching, answered the question on the broadcast of the 2016 4A state football championship–which Camas won.

Copeland said he has always had coaches monitoring his arm, which he knows is for his own good.

“I like to compete, so I’m not just going to take myself out,” Copeland said. “I definitely feel like my whole life I’ve had someone there to moderate it, not let me do too much.”

But not every young player has a coach like that.

Any advocate of a pitch count in Washington can likely recall one extreme incident three seasons before the rule was put into place.

In May 2014, a pitcher at Rochester High School made national headlines for throwing 194 pitches in 15-innings of a postseason game against La Center. It struck a chord with advocates for player safety, and even Major League Baseball ace David Price, who suggested the coach be fired for allowing him to stay in that long.

Rochester won 1-0 and the player, Dylan Fosnacht, finished with 17 strikeouts, three walks and gave up seven hits in an outing he later defended amid backlash directed at his coaches.

“We talked to him every inning, and he said he felt comfortable, he felt good, and he’s a little competitor,” Rochester coach Jerry Striegel told the Centralia Chronicle after the game. “He didn’t want to come out of the ballgame. He wasn’t very pleased when I took him out in the 15th.”

At that time the WIAA did not have a pitch limit–only a rule forcing players to take a minimum of two days rest between games where 40 or more pitches are thrown.

After a year with the pitch count in place, some see it as an early success. Others acknowledge its importance, but would like to see fine-tuning.

And it appears those concerns may be alleviated. The WIAA executive board proposed an amendment to the pitch count rule that would allow a pitcher to finish an at-bat if the count is at 100 or less when the at-bat starts.

The rationale? For the sake of continuity–not having to take a Casetta-Stubbs out in the middle of an at-bat in the seventh inning of a state title game.

“Most other states allow the pitcher to continue the at-bat with no adverse consequences,” the proposal argues.

Players like King’s Way’s Sam Lauderdale, a left-handed pitcher committed to Washington State, don’t come near 105 pitches on their best days.

“105 is a lot for a high school arm, your arm isn’t fully developed,” Lauderdale said. The senior has thrown as many as 103 pitches, which was in the state semifinals last season, but he typically aims to keep his count below 70.

But most 1A programs don’t have the luxury of rotating two Division-I college-level arms. That was one of the arguments for keeping pitch counts higher.

Many smaller schools simply don’t have large pitching rotation. King’s Way has eight pitchers to play three games a week. At University of Portland, Swenson had 14 pitchers for four games per week.

“I tried to emphasize it’s not about us, it’s not about the schools, it’s about the kids’ arms and being able to pick it up when they’re older and play catch with their kids, do some things like that,” Swenson said. “In the case here there’s a couple arms that are pretty special that need to be looked after to make sure their careers aren’t in jeopardy just because somebody wants to run them out there every three days.”

The change, in some cases, is jarring to coaches.

“Everybody is different,” Swenson said. “Tim Lincecum at Washington could throw 135 pitches and it was no big deal. There was definitely a little bit of individuality that needs to be accounted for, but to just have a universal rule that allowed them to throw so many pitches was, for me, setting us up to really have some issues.”

The proposed amendment will be voted on by the 2018 representative assembly between April 27 and May 4, and if passed, will be put into place at the start of the 2019 season.